At King’s Cross, a Channel Tunnel terminal, a new Underground concourse and a new station for Thameslink are being built. At the bottom of an open shaft about twenty feet deep, walled partly in concrete, partly in brick and partly in raw clay, two mechanical diggers on caterpillar tracks are at play. They are too small to have cabs. Operators in yellow coats and hard hats direct them by way of long cables ending in consoles on which they push joysticks, as children do to send toy racing cars whizzing about. Down there in the mud the diggers heap spoil into piles. A full-size earth-moving machine reaches down, claws out bucket-loads of earth, concrete and brick and dumps them into skips.

I know this hole in the ground well. The contractors supply generous windows of clear plastic, and you can spend a minute or two every day keeping track of progress. Work on the Channel Tunnel itself, on the ring main for London’s water, and on the Jubilee Line extension, happened out of sight. Engineering isn’t always a spectator event, and new technology often lacks the drama of older ways of building. For example, the Victorian building at St Pancras has Gothic overtones and can be read in the way you read a cathedral vault: the eye follows ribs and feels the stress as the weight the ribs support is brought safely to the ground. The new train shed, now open though not yet complete, is a large, flat-roofed box: post-and-beam architecture, visually more primitive than the old building.

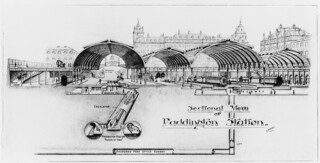

There isn’t much drama or grandeur evident from the outside of Paddington Station, the culmination of Brunel’s work for the Great Western Railway. It stands in a cutting, and the hotel at the head of the platforms conceals the long, glazed vaults of the train shed. Charing Cross and St Pancras are also fronted by hotels, but they don’t push the station entrances to left and right the way the one at Paddington does.

I took the train to Maidenhead from one of Paddington’s more obscure, post-Brunel platforms. The last of the broad-gauge lines Brunel specified were replaced with standard gauge in 1892. (In one weekend – from daybreak on Saturday, 21 May to 4 a.m. on the Monday – 4200 workers converted 171 route miles of the main line. The Monday mail train ran on time.) But Brunel’s decision to specify something bigger, better or more daring than the norm was logical, not hubristic: he believed it would result in a faster, safer, smoother-running railway.

His bridge over the Thames at Maidenhead was also a response to practical problems. There isn’t much to see from the train, but get out, walk back along the riverbank, look at the bridge from below and you sense that something remarkable has been done. A plaque put up in 1975 explains:

1838 THE SOUNDING ARCH

I.K. BRUNEL DESIGNED THIS BRIDGE

THE BRICK ARCHES ARE THE WIDEST

AND THE FLATTEST IN THE WORLD –

EACH SPAN IS 128 FEET WITH A

RISE OF ONLY 24 FEET.

‘Sounding Arch’ because there is an echo. ‘Flattest’ because every foot in the height of the bridge was a foot which would have had to be added to the height of miles of track-carrying embankment. Think of the mud in the hole at King’s Cross, then think of navvies with only picks, shovels and wheelbarrows to move it. The arches are wide because the bridge crosses the river in two spans. Architecturally it is as plain as you can get: the beauty of the thing is in the leap of the arches.

Diesel-electric trains pass over it now. In the 1840s steam engines of the Firefly class crossed it at what were exceptional speeds – 50 mph and more. To get an idea of how it felt then, go to the National Gallery and look at Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, which shows a train crossing the Maidenhead bridge. Rain skeins across the picture from the right, sunlight breaks through, white steam and smoke from the engine’s stack are blown to the left. When it was exhibited in 1844, the Times critic said that railways had given ‘a new field’ for Turner’s ‘eccentric style’, ‘the dark atmosphere, bright sparkling fire of the engine and the dusty smoke’ forming ‘a very striking combination’.

As well as Turner’s exercise in railway sublime, Steven Brindle’s new book about Paddington Station includes W.P. Frith’s The Railway Station, painted a little under twenty years later.* By then the railway had passed as a subject ‘out of the orbit of landscape into that of Victorian genre’, as John Gage says in his book about Turner’s picture. The Railway Station shows a train about to leave Paddington; the detail of the architecture is correct – Frith had photographs taken for reference – but it is the partings and greetings you look at first: detectives make an arrest, boys are sent off to school, a soldier holds up a child. The poetry of speed has no part in it, except in that railways bring people together and put them asunder more swiftly – engineered structures shaking social ones.

When Turner’s great picture was being painted there were plenty of people (Ruskin, Wordsworth) who deprecated the noise, smoke and destruction of the landscape railways inflicted. There are plenty now who have qualms about the ways of being taken quickly from place to place which have followed. They promised new freedoms – the open road in an open car, the unsullied sky – but also produced the bondage of jammed motorways, airline check-in queues, noise and smog. There is a famous description of a short, square man leaning out of a train window during a rainstorm, who later turned out to be Turner. An aeroplane open to the skies might have suited him even better.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.