Not many Edinburgh residents collect beach-cast seaweed, but when a winter storm leaves a strandline deposit on Portobello beach, it feels to me like a gift or a visitation from another world. Seaweed has a wonderful benthic weirdness; it’s so rubbery and alien, yet when you add it to the compost heap it becomes velvety, almost ambrosial. In the 17th century, fistfights would break out on the Forth foreshore over who had the right to collect ‘sea-ware for manuring the ground’. These days rotting kelp and bladderwrack are less sought after. People expect a clean beach, so every week the council combs the sand with a tractor and a mechanical surf rake. The resulting harvest is riddled with plastic – wet wipes (polyester or polypropylene), drinks bottles (polyethylene terephthalate) and assorted marine litter – so it gets dumped in landfill. The cost of a clean beach is paid in greenhouse gas emissions, and in reduced foraging for shorebirds like the turnstone, which has been on the UK amber list since 2015. I often try to claim my share ahead of the council tractor, filling a four-wheeled cart that I pull by hand. I use an implement that in Scotland is traditionally called a ‘graip’ and resembles the pitchfork in Grant Wood’s American Gothic. I prefer to work in darkness: there are fewer questions that way. One weekend afternoon when I was straining with 100 kg of kelp along the promenade, someone stopped to ask: ‘Are you gonnae eat that?’

The ingredients of compost are dead things or, as the YouTube gardener Bruce Darrell put it, ‘anything that was recently alive’. I like this definition. Making compost is often beset with prohibitions – you’re not supposed to add meat or dairy or citrus or cooked foods or fish or perennial weeds or bones or rhubarb leaves or diseased plants – and there can be good reasons for these exclusions, from discouraging rats or pathogens to the fact that some things take too long to break down. But what’s the worst that can happen? I now ignore compost orthodoxy in favour of this one rule: ingredients must have been living (or, like paper, be made from something living). In addition to seaweed, my preferred compostables include autumn leaves, kitchen scraps, garden waste, grass clippings, shredded manuscript drafts, the bedstraw from my neighbour’s guinea pig, cardboard, wool insulation for our frozen cat food, sawdust and spent coffee grounds from our local café. As the availability of these feedstocks varies throughout the year, my compost mix is never quite the same. But I always include two staples: fibrous material like wood chippings or rose prunings to create tiny air pockets. Then water. After that, it just takes time.

There’s a eucharistic mystery to the biochemical transformations that follow. Things fall apart. They decompose and recompose. Thermophilic microbes foment anarchy in the pile. Even the lignin of plant cell walls – the stuff that makes wood woody – loses all conviction. Buoyant seaweed doesn’t need lignin for support so it breaks down all the faster. After just a week or two, a mop of bladderwrack still holds the same shape, like a memory of itself, but has turned white with actinomycetes bacteria. I add cart after cart of seaweed and autumn leaves to the heap, but the volume seems constant, so that what is left is a rich reduction, like stock or gravy.

Making compost isn’t difficult. Pile up some dead things and compost will happen. If you have ever wondered if it’s okay to toss an apple core in the woods, then you have considered the efficacy of decomposition. The horticulturalist Charles Dowding’s ‘no-dig’ gardening philosophy holds that if we minimise soil disturbance, we protect the mycorrhizal networks that act as the delivery systems for nutrient exchange. He argues that by leaving the spade in the shed and letting a layer of compost do the work, we can improve fertility and water retention, while also producing a lot of food. His market garden, Homeacres, in Somerset, is the test bed for this theory, and the backdrop for his prolific social media output (700,000 subscribers on YouTube, 500,000 on Instagram). Dowding’s garden isn’t pristine or manicured but in austerity Britain there’s something appealing about its cornucopian appearance – packed rows of vegetables against a dark canvas of compost.

Dowding uses compost as a top dressing for vegetable beds, replicating the natural accumulation of leaf litter. He recommends an initial four-inch covering, then one inch annually after that. For most gardeners that’s a lot of compost, so he has published a practical guide, Compost (Dorling Kindersley, £14.99), on how to make it at home. Composting is a bit like making coffee: there are many ways to do it, and most of them are good in their own way, though people usually have a favourite. There’s the ‘dalek’ bin, a plastic container with a lid at the top and a bottom open to the ground (a common garden method). The dalek is a manageable size and any problems can be solved by adding ingredients or water or forking it over. There are fussier methods like the rotating tumbler (mine broke within weeks), or vermiculture farms for brandling worms. An insulated hot bin will digest most things – I’ve fed it everything from chicken carcasses to my lockdown beard – but keeping it up to temperature requires care. Trench composting does what it says: dig a trench where you intend to plant, fill it with green waste and cover it up. There are small-scale anaerobic fermentation methods that can be done indoors, using bokashi bran, for example (though the finished product needs further decomposition). At the other end of the spectrum is the Johnson-Su bioreactor – a shed-sized super-composter held together with landscape fabric, wire mesh and sheer commitment. I quite like the idea of it, but I’m intimidated by the guidance to use 800 kg of material to get it started (‘this may seem like a lot,’ one manual says, ‘but you’ll find that you can never have enough of the resulting compost’).

Dowding devotes most of his attention to the method that, after 25 years of experimenting, I, too, have found to be the simplest and the best: the compost pile or heap. It couldn’t be easier. Put the dead things in a pile. That’s it. It helps to have a heap that’s a little bigger than, say, a dalek bin. Dowding bounds his with old pallets to form a kind of cube that holds a sufficient volume to retain heat and moisture. After that, the considerations are familiar to us as humans: does it have enough water, and a balanced diet of proteins (nitrogen-rich green things) and carbohydrates (carbon-rich brown things), perhaps with a bit of roughage thrown in to create air pockets? The process is faster if you keep an eye on the ratio of green to brown: three parts green waste to one part brown is a more useful rule of thumb than the technically ideal ratio of thirty parts carbon to one part nitrogen (lots of green waste is already carbonaceous and the exact C:N ratio of ingredients is obscure). For green waste, think food scraps, grass clippings and hedge trimmings; for brown, office paper, cardboard, autumn leaves, straw or hay. But don’t take the colour too literally. Coffee grounds, for instance, are considered green waste but have a C:N ratio of 20:1. In short, mix up greens and browns and avoid the pile being too soggy or too dry. It will just work.

Warmth is a sign that good things are happening. In summer, a new pile can get hot within a couple of days. I prod it with a long-stemmed compost thermometer, although this is entirely unnecessary – I just enjoy seeing the needle soar. There’s something excessive and beguiling about the heat. I used to doubt old Highland tales of barefoot children burned by jumping in the dung heap after byre muck was emptied in the spring. Now I understand. My heap is a modest size – a bit over a cubic metre – and regularly exceeds 60°C (a hot bath, for comparison, is about 45°C). I’m on a Facebook group called ‘Composting, just composting’ where there’s always one guy – that’s me here, I guess – going on about his compost being so hot. (I’ve also seen male birds do this: the Australian brush-turkey, Alectura lathami, scratches together a car-sized mound of leaf litter and manages to compost it at the perfect temperature for egg incubation – all to impress his mate.) Some Facebook posters even worry about spontaneous combustion, which I took to be just another flex, until on the hottest day of 2022, a wildfire started in a dry heap in the village of Wennington on the edge of East London and burned down eighteen houses. Compost doesn’t need to be hot and very often it isn’t. High temperatures can usefully kill diseases, pathogens and weed seeds – and rats don’t like it – but may also kill some of the fungi that are beneficial for nutrient exchange. Compost that never gets hot is usually lighter in colour and can be more bioactive. If you have a neglected bin of cold dalek compost, congratulations, you have done everything right.

Buying compost would be much quicker and easier for me than making it. Edinburgh’s garden waste is collected by the council, hot-composted in monumental windrows in rural East Lothian and sold to gardeners at six pence a litre. I make my own compost so that I can convince myself that even when the world seems socially and ecologically broken there are still mechanisms for recovery: it shows that change is possible. Composting is a simple habit of composition or gathering together that integrates past fragments into a future whole, so that what matters is not the individual ingredients but the fertile new thing they can become.

Compost also makes certain ecological realities apparent. After removing all the plastic I could see when harvesting my seaweed, I recovered another two kilos, mostly wet wipes, from four cubic metres of finished compost. Other plastic debris is evident from its primary colours: fragments of baler twine, confectionery wrappers, pen lids, bottle tops, disposable masks, mini bubble wands and much else that I can’t identify. There are also unseen contaminants. Hay or animal manure can contain aminopyralid residue. This commercial weedkiller, introduced to the UK in 2005, adheres to plant material so effectively that not even the digestion of ruminants or microbes will disable it. The first sign that a batch of compost is affected is that young plants grow pale and distorted. It’s unsettling to realise that homemade compost can be actively damaging to plants.

I sometimes wonder whether my love of compost is a response to the dispiriting cleanness of modern life – the spray’n’wipe, the no-touch flush, the sanitisers and disinfectants. The compost pile stands in productive contrast to a domestic order founded on the concealment of waste. We so rarely have to deal with our own shit, and this avoidance extends beyond sewage. It’s true that it’s easy to rhapsodise about the wholesome messiness of compost when you’re historically detached from the terror it once held. A branch of my family survived the 1832 cholera epidemic in which half of their Easter Ross village died. Eleven people were buried in a single day and another nineteen later the same week. Thinking that the disease came from a miasma – the knowledge that it was water-borne was decades away – the authorities ordered that all dung heaps and middens be destroyed. In those days, decomposition was contagion, and this belief was an ordering force in the world. ‘The dream of purity and freshness was born from the omnipresence of muck and dust,’ John Berger wrote in his essay ‘A Load of Shit’. ‘This polarity must be one of the deepest rooted in human imagination, intimately connected with the idea of home as a shelter – against many things, including dirt.’ For Walt Whitman, ‘this compost’ was simultaneously vile, the stuff of putrefaction and ‘distemper’d corpses’, and redemptive: ‘It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions … it distils such exquisite winds out of such infused fetor.’

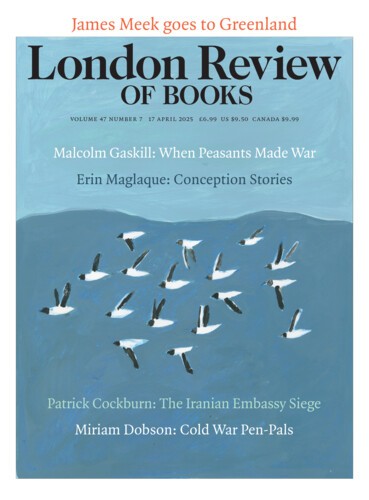

This sense of redemption now feels uncertain because too much of our waste will not decompose. Our abiding desire for purity and freshness means that seven million wet wipes are flushed down the toilet every day in the UK, binding together sewer fatbergs or landing on riverbanks and beaches. At Hammersmith Bridge in London, an agglomeration of wet wipes and sediment on the banks of the Thames was a metre deep and the length of two tennis courts. This wet wipe problem is not going away. Even if the UK government brings in the expected ban on single-use plastic wet wipes, their bioplastic replacements will produce similar outcomes unless there is a change in the way they are disposed. Biodegradable plastics are a theoretical rather than a practical solution, as anyone who has tried to compost them will know. UCL’s Big Compost Experiment, a citizen science project led by materials researchers Mark Miodownik and Danielle Purkiss, found that the majority of certified ‘home compostable’ materials did not in fact disintegrate in a garden heap. The anaerobic digestion facilities that process food waste are not configured for bioplastics, which take three to six times longer to break down and so are usually removed as a contaminant; the true fate of most compostable plastics is landfill or incineration. Just because a bioplastic wet wipe can theoretically decompose given the right industrial system does not mean that it will break down when it ends up on a riverbank. We need to use fewer of them. And not flush them at all. The LRB arrives in a potato-based polymer wrapper that I usually put in the landfill bin (I’m told this will soon change to a paper wrapper). Few things are harder to compost than those branded as ‘100 per cent biodegradable’.

Despite its plastic contaminants, I love my seaweed and what it adds to the garden. I am grateful for it, as other growers were before me. The 17th-century traveller Martin Martin described the attempts made by the inhabitants of Ness on the Isle of Lewis to secure a supply of seaweed: kelp and tangle improve soil structure and are important sources of potassium, which is lacking from the acidic peat soil of the Hebrides. Each household would bring a bag of malt to the church of Maol Rubha so that it could be brewed into a special ale. At Hallowtide, someone waded into the water to petition the water spirit Seonaidh: ‘I give you this cup of ale,’ they shouted, casting it into the waves, ‘hoping that you’ll be so kind as to send us plenty of sea-ware for enriching our ground.’ The islanders then returned to the church, blew out the altar candle, drank the remaining ale and spent the rest of the night dancing. Martin describes it as a ‘solemn anniversary’. This makes sense to me. Fertility rites are a serious business that reflect our debt to the earth – not merely nostalgie de la boue, or a wallowing in the dirt, but a desire for abundance and fullness – for the alchemy of new life born from dead things.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.