It was noisy in Harry H. Tombs Ltd, the New Zealand print shop where I served a small part of an apprenticeship that would have made me a compositor.* I worked upstairs in the composing room where the rhythm was set by the Linotype machines: the tap of the keyboard, the rustle of the matrices sliding from the magazine into their place in the line, followed, when the line was full, by a heavy thump as the spaces were wedged home. There were clanks and bangs as the line of matrices was offered up to the mould and the molten type-metal that glistened in the crucible behind was injected. The hot, bright line of newly cast type joined others in the tray with a metallic slither. Meanwhile, we hand-compositors stood at our frames and quietly clicked type into our composing sticks for the odd heading or display line, or dissed it, dropping used type back into the case with a louder click. We assembled the metal lines of type (called slugs) and titles and any other elements of the printed page, and grouped them together with other pages for printing, creating what was known as a forme. From time to time there would be a thump as one of us heaved a forme (four, eight or sixteen pages of type weigh a lot) up onto the stone – the metal table on which they were put together. The pages of the forme were wedged into a metal frame, the chase, where they were held firm by quoins (wedges). A hoist creaked as the finished formes were lowered to the ground-floor press room. That had its own sounds. The hiss of air as suckers picked up a sheet from the stack at one end of the big flatbed press and passed it on to be grasped by the cylinder. The sound of engaged gears as the sheet was rolled against the inked type on the moving bed of the press and then released to be carried onwards and added to the pile of printed sheets at the other end of the press. What had been Linotype slugs, type and illustrations upstairs were now pages of the New Zealand Commercial Grower or a scientific paper on the best way to collect ram semen. Each of the three presses had its own voice. It was an inky world dominated by machines that had been milled and drilled from heavy castings, which needed grease and oil to keep them healthy, and a machine minder who, like a good childminder, had an ear tuned to unexpected sounds as well as an eye tuned to imperfections in inking.

I have spent most of my life following up what I began then. I still work with print and play with words, but the sound of typesetting is now the tapping of a writer at a word processor, and I move pages about on my computer screen not on a stone. The formes we sent down to the press room are now files sent over the wire to a printer. Typesetting, once handwork, is now screenwork, a branch of computer graphics, and the presses that output printed sheets are governed electronically. It will be some time before printing on paper disappears, but in many fields it is being edged out. The page has become a graphic image that can be printed, or output to a screen where texts, which long ago made the transition from scroll to book, are once again scrolled. Some ebook software generates images of turning pages – an anachronism as odd in its way as the steam train on signs that warn of a level crossing. Odd, but not surprising. ‘Book’ means both the object you can throw and the words you read. Images of pages make the nebulous, cloud-borne text more substantial. Print itself is losing its primacy; newspapers, book and magazine publishers are looking for ways to defend their properties with web-based versions and extensions. Ebooks have begun to sell better than hardbacks.

It isn’t surprising either that letterpress printing – the essentials of which changed little over the first five hundred years – is dead as an industrial process, or almost dead in this country anyway. Someone who came to printing in the 1950s wanting to make books like the ones he or she had read and admired knows that little remains of the constraints, the rectangular grid imposed by type and chase, the limited number of typefaces and sizes of type, which set limits (including an architecture as orthogonal as the warp and weft of woven fabric) on the look of typeset pages. Hot metal typesetting sped thing up: instead of having to arrange existing metal type by hand, the compositor took prepared lines of text from the casting machine, which created new type as quickly as you could tap out the letters on the keyboard. But printing remained an entirely physical business.

Typefaces are called that because it was the two-dimensional face of the three-dimensional piece of type that carried the shape of the printed letter. The type has disappeared but the word ‘face’ still feels right. Typefaces, like human faces, are schematically identical yet individually recognisable. The part of the brain dedicated to face recognition differentiates thousands of them on the basis of small differences in the size of nose, eyes and so forth. Those who work with types know their faces in much the same way. The response of people who know (or think they know) nothing about them shows that they still stand in the shadow of the old technology, and the written texts from which type designs derive. Readers’ ideas of how words should look necessarily change very slowly.

For this reason, print history is as relevant as that of any other aspect of written language. Designers of type in the machine age have been well informed about its history. Many practitioners and historians, including Harry Carter, whose 1968 Lyell Lectures, A View of Early Typography, are still the best account of the early history of type design, have known how to cut a punch. As well as many typefaces for print, his son Matthew designed Verdana and Georgia, faces adapted to screen display, for Microsoft. Others, like Eric Gill and Edward Johnston, were lettercutters in stone and calligraphers. There is software that makes the preparation of digital faces technically straightforward, but those who use it best (like Fred Smeijers, who designed Quadraat, the typeface this paper is set in) often – inevitably you might say – use historical material as a starting point.

The past of letterpress printing is cherished by many, type specimens and commercial records are collected, interviews with old men recorded and artefacts – punches, moulds, the types themselves – preserved. The material that has survived from the first four hundred years is not bulky, abundant or inordinately demanding of space. The proportion that is on paper is library material. On Typefoundry, a blog on ‘documents for the history of type and letterforms’, you can find a list made by James Mosley of the important collections of other material: punches, moulds and so on. It is a resource that is well used and would be better used if a more comprehensive account of what is held and digital records of it became available. From the first (as Carter shows), the trade in matrices was international; the time is ripe for an international repository of information. Digital technology could have been made for the job. But the large-scale relics of industrial printing are not so easy to deal with. Does it matter, to take one example, if Monotype casters, punches and matrices, and the machinery that made them, are reduced to a few museum pieces?

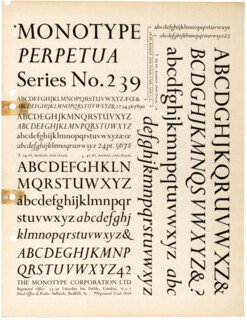

Monotype setting was as good as it got. When I was serving my time with Harry H. Tombs, I already knew that for high-quality printing Monotype, not the Linotype clunking away in the composing room, was the preferred machine. There was some snobbery in this. Linotype was used for books, particularly in America, but American books were less mannerly than British ones and New Zealand was only just emerging from aesthetic Britocentrism. I was fogeyish in my tastes even by those standards. But Harry H. Tombs had, earlier on, been a rather adventurous printer and publisher, and in the back office there were issues of the Fleuron, a handsome annual of typography issued between 1923 and 1930. The last volume had specimens of faces that Monotype had issued or would later issue. There were Venetian 15th-century revivals (Centaur and Bembo) and new faces (Gill’s Perpetua and Jan Van Krimpen’s Lutetia). But it wasn’t just a matter of faces: I knew that some Linotype faces were very good indeed; my feelings were more like those I came across when I read Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Beginning of Spring. It’s set in Moscow in 1913 (the Monotype machine had, by then, been around for just more than a decade). She describes what Tvyordov, the head compositor in a printworks owned by an Englishman, thinks about mechanical typesetting:

There was no mystery about Tvyordov’s attitude to the machine room. Linotype, he felt, was not worthy of a serious man’s carefully measured time. It was only fit for slipshod work at great speed. To make corrections you had to reset the whole line, therefore you had orders not to do it. The metal used was wretchedly soft alloy. Monotype, after some consideration, he tolerated. The machine was small and ingenious, and the letters danced out as they were cast from the hot metal, separate and alive. They weren’t as hard as real founder’s type, still they would take a good many impressions and they could be used for corrections in the compositor’s room. When, or even whether, Tvyordov had been asked for his views was not known, but Reidka’s did Monotype and no Linotype.

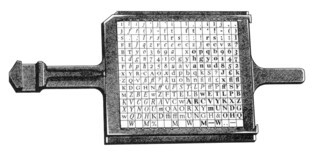

I read that with feeling. A Monotype machine, like an expensive car, was clearly a masterpiece of mechanical engineering. Was and is: the Monotype Corporation gave up making them late in the last century, but there are still many in use around the world. (What Tvyordov doesn’t consider – the separate keyboard that produces the punched paper tape that drives the caster – has no affinity whatsoever with hand composition. What could be less like filling a composing stick with type, checking it as you go, than keying in text that will only become visible when the tape has been output as type on another, quite different machine? You can now link computers running page-makeup software to Monotype casters. I can’t imagine even a hot-metal purist wanting to do it any other way.)

The Monotype caster, then, is a beautiful example of a machine that stands at the border dividing those you can watch as they turn, push or slide pieces of metal over one another from those that depend on electronics. In principle its workings are simple. Following instructions punched in a paper tape, a frame containing a matrix for each character in the font is placed, letter by letter, above a mould which is adjusted to the appropriate width – narrow for an ‘l’, wide for a ‘W’ and so on. A nozzle injects hot, liquid type metal (an alloy of lead, tin and antimony) into it. The letters ‘dance out separate and alive’, as Fitzgerald puts it, and, from these letters, words and lines build paragraphs and pages.

Such machines are mechanically comprehensible; a computer loaded with graphics software is not. When a broken shaft stops a machine, you can visualise it. A conflict in the software that makes a page go haywire has no mechanical correlative: it is a mistake in instructions fed to the machine. You know what goes into the box and what comes out, but the detail of the part played by what a keystroke delivers to a page make-up program to create the files that drive a printer is opaque, and not to be understood in terms of the disposition of the parts of a mechanism.

Is a hankering for Monotype setting to survive more than a sentimental attachment to visible mechanical ingenuity? The question would be theoretical if, in 1992, when the Lanston Monotype Corporation factory at Salfords, near Redhill, was being sold off by the receivers, a group of enthusiasts led by Susan Shaw had not been able to persuade the National Heritage Memorial Fund to subsidise the purchase of a vast amount of Monotype material: machine tools, casters and matrix and punch-making equipment, as well as the company’s paper archive and hundreds of thousands of copper character patterns. While it was still at Salfords, the production of matrices went on. In 1992, a building in London was found for the collection. The first steps towards the foundation of the Type Museum – later renamed the Type Archive – had been taken.†

Sue Shaw’s first jobs were with publishers. Later she set herself up as a typesetter and printer. I visited a couple of times to look at what was stored in the archive. It was like a huge, unwrapped present – at that time it wasn’t open to the public and much of the material was waiting to be shelved (in the original racking that came down with the rest of the material from Salfords). It was, however, alive. It says something for the attraction of Monotype that two former Salfords employees have been willing to carry on as volunteers, to the extent that the Type Archive is still able to fulfil orders for matrices. A large one from India paid for the transfer of a great deal of the material from Redhill to Lambeth (a good proportion of the matrices exported by Monotype were always for non-roman character sets).

My ambition was to work on books of a traditional kind, books where a millimetre or so on the margins, a fraction more or less space between the lines, the choice of paper, the way the book opens and whether it stays open, were important questions. No other design craft is so inherently conservative. The characters (‘glyphs’ in computer-speak) of the printed Latin alphabet have changed less than language, spelling or handwriting. Despite that, the details that distinguish one typeface from another carry a load of cultural and temporal information. As you move on from the mid-15th to the end of the 19th century you can make better and better guesses as to the age of a printed page by just looking at the type. When, in the 20th century, many new faces claimed (with some degree of truth) to reproduce, for example, the types Jenson used in Venice in the 1400s, or those Fournier cast in France in the 1700s, revivalism itself became a style. Awareness of these differences probably exists subliminally: research many years ago showed that scientists expected their papers to be set in ‘modern’ fonts. I doubt if they do now.

Digital type, which began as a rather crude approximation of metal type, has become wonderfully refined. It has never been easier to make new types, and things that exercised the skills of punch-cutters – in particular the fit of letters (the spacing that makes the pairing A V wide and MM tight) are still dealt with in kerning tables which can be fine-tuned if you have particular problems. That continuity is one reason to preserve old machines, old type, old tools – type designers have not exhausted their practical usefulness.

When you ask what should be preserved and how it should be used, however, you find that different constituencies have different priorities. All of them want access to the products of the press: books and various kinds of ephemera. The preservation of documents kept by the printing and book trades – letters, day books, accounts, diaries and so forth – is important, but all that is on paper, amenable to the discipline of librarians and archivists. Historians of the craft of printing and type, though, also need access to things: punches, matrices, type, printing presses and typecasting and typesetting equipment. Beyond that there is the information, passed on from generation to generation, that survives (for now) in people’s heads.

To keep the knowledge of handprinting alive, letterpress printing – the plainest link with the craft as it existed over its first five hundred years – must also be sustained. Letterpress has its own aesthetic. A raised surface – type and blocks – is inked. When it is pressed against a sheet of paper, the raised surface digs into it. It was the tactile quality of the object as much as the detail of the image that distinguished the private press books made around the end of the 19th century from the smooth, commercially printed pages of the books they wanted to improve on. Handmade paper and an even, black impression make the page a three-dimensional object, not a two-dimensional image. But you can have too much substance. An over-attachment to it made many private press books precious. A kind of Midas touch made them unreadable: not because they were illegible or ugly but because that kind of fine printing went against the nature of the book as an object to be picked up and, while you read it, ignored. The book as art object was a dead end. Commercial printing and publishing, on the other hand, did seem to have lost touch with whatever it was that made one of Aldus Manutius’s little books from late 1400s Venice so modest and attractive. Through the first half of the 20th century, commercial publishers and printers and university presses brought a seemliness to British book printing that was sound and conventional, like a St James’s Street shoe. During those years the ‘impression’, the way type dug into the paper, almost disappeared while, as Mosley puts it, ‘the skills of the typefounder, the compositor and the machine minder, and the quality of the machine technology that they used, reached a level of perfection that it is a bittersweet experience for us to look at now.’

Good book design, as I understood it in the 1950s, was the product of commercial letterpress printing. The books followed conventions derived from the past. In what I absorbed turning the pages of the Fleuron in my Wellington lunch breaks, there was no hint of the Bauhaus or the Russian Constructivists, or indeed any suggestion that modernism of any sort had a part to play in print design. My boss at Harry H. Tombs, Denis Glover, when he was in Britain during the war (he commanded a landing craft in the D-Day landings), sought out ‘printers and bookmen’. He talked to me about John Johnson, the Oxford University Press printer, and in a poem, ‘Printers’, published much later (in 1964) names him and other men he had met. These were authors I had read, or read about, in the 1950s: Oliver Simon, whose Penguin Introduction to Typography was as close as I got to finding an authoritative textbook, and Stanley Morison (‘Then Stanley Morison squatted me on the floor/To examine big letter designs and pore/Over the refinement of serifs’). Johnson told Glover he shouldn’t look to make a career in England. He was surely right. Denis was a boxer and sailor as well as a poet: ‘bookman’, with its tweedy overtones, didn’t fit his inherent contrariness.

It’s hard for me now to acknowledge how backwards-looking my ideas about design were. But it was books I wanted to work with, and for me that meant texts (not pictures), hot metal typography and respect for the past. I liked the idea that bookishness – the history of printing and publishing, the work of the bibliographer Ronald McKerrow – could be a thing of practical experience; my friend Don McKenzie, in a paper called ‘Printers of the Mind’, showed the way theoretical views of what happened in a print shop were entirely inadequate when examined in the light of what he had learned in a meticulous study of the archives of a real printing house (Cambridge University Press). The mix of practical bookmaking, literary publishing and print history fitted my fogeyishness very well. Had I gone to art school and studied graphic design it would have been different, but I was both snobbish about the commercial part of ‘commercial art’ and intimidated by its stylishness – the unreachable suavity of the fashion illustrations in Vogue, the inventiveness of Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar and the cool corporate chic of Paul Rand at IBM. When, saving for a ticket to England, I made drawings for schoolbooks, the illustrators I admired were English: people like Edward Bawden, Edward Ardizzone, David Gentleman and John Minton.

So, for most of my life, it was books I stuck with. More often illustrated books and exhibition catalogues than straight text, but even those, even in hands as expert as Brodovitch’s, could never have been the works of art he made of Richard Avedon’s Observations, a proper picture book in which the comments by Truman Capote, set in italic, are something you might turn to even if the utterly memorable photographs did not draw you on, insisting that you not break the rhythm of the visual riff of contrasts and juxtapositions that continues, page after page.

The texts I worked with, even when illustrated, were as important as the pictures, and the craft of making a hybrid object could never achieve the coherence of the grand photographic picture books established in albums of work by Avedon, Penn, Lartigue, Klein and Cartier-Bresson. But improvements in offset lithographic printing did make the integrated illustrated book a cheaper, neater product. Cookbooks, popular books about history, gardening, art – about any subject that is illustratable – draw on the asymmetrical liveliness of the magazines that in turn made typography a small part of a wider graphic medium. But that is our own age, the age of the page-as-image, which hardly differentiates between magazine, newspaper, book and screen design. The unillustrated cookbook is now, I guess, almost unpublishable. Books have become heavier, paper a characterless surface with the smooth brilliance of a computer screen.

The total that should be preserved is much wider than the field outlined here, which excludes, for example, photogravure and thus the volumes of black and white reproductions of paintings that the Phaidon Press produced in Germany and England in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. It ignores the huge field of hand-drawn lithography, and thus a vast amount of music printing and commercial printing. But words set in type and printed on paper constitute a subject large and coherent enough to have its own archives, museums, workshops and what have you.

Which takes one back to typefaces and the Monotype machine. If you are making a book with no pictures, the text type, which in a picture book or illustrated magazine registers as a grey mass, punctuated perhaps by a heading, initial or quotation, asserts its individuality. The ‘bookmen’ I admired were essentially literary: Glover, as poet, publisher and printer, condensed the whole book-making process into one career. The text-only book, the reading book, is something you pick up, hold, take to bed, carry about with you. To design a book is to decide on its weight, shape, ease of opening, ease of reading, things as important as the look of the page.

Does this history matter? If it does, which skills and tools must be preserved? The quantity and nature of what needs to be stored and made accessible is not monstrous. The downside is the speed with which links between old and new ways of working dissolve when a large organisation decides to outsource its printing. The OUP was using its own hand-cast 17th-century type well into the 1950s. The historical material may not be lost, but without a connection to a working printing house its use becomes archival and antiquarian. If big machinery – the presses and typesetting machinery of, say, a moderately large book-printing works of around 1950 – are to be preserved as more than a curiosity they need to be shown at work. But printing is a business, it doesn’t fit the model of flypasts by World War Two aircraft (a little less well represented at every anniversary). It only makes sense to keep mechanical, hot metal setting alive, commercially or otherwise, if a case can be made for its use. If it can’t, it must be given a fond farewell, as manuscript-making was.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.