In 1897 or 1898, Edouard Vuillard gave Félix Vallotton one of his most important paintings. Vuillard’s Large Interior with Six Figures appears in two of Vallotton’s paintings, hanging on the wall and reflected in a mirror. It is quintessential early Vuillard: an intimate world ruled by women, jigsawed into place by wallpaper, curtains and rugs, any anxiety or conflict muffled by patterns and layers of plush. Vallotton’s interiors, by contrast, trade on male-female tension and gaping empty spaces. The smooth blocks of saturated colour amplify the sexual frisson. Despite their different temperaments as artists, Vallotton and Vuillard were both reserved men who navigated the cultural efflorescence and political turmoil of fin de siècle Paris side by side. Vuillard is much better known, but the first major survey of Vallotton’s work in the UK is now on display at the Royal Academy (until 29 September), almost a century after his death.

He was born in 1865 in Lausanne to a chemist who later became a chocolate maker. At 16 he moved to Paris, where he studied at the Académie Julian and copied paintings in the Louvre. He became captivated by Japanese prints after visiting the Universal Exhibition of 1889 – a key source of inspiration. With no financial backing, he took on various jobs during the 1890s: working as an art critic for a Swiss newspaper, helping to restore paintings for a Parisian dealer, illustrating a wide range of books, and churning out prints for the magazines and political papers then proliferating in Paris (his most important collaboration was with La Revue blanche). He also wrote three novels and eight plays, two of which were staged.

In the early 1890s Vallotton began to attract attention for his boldly synthetic, black and white woodcuts and in 1893 he joined the Nabis, a group of young avant-garde artists that included Bonnard and Vuillard. The Nabis liked nicknames, and Vallotton’s was le nabi étranger (‘the foreign Nabi’). He volunteered to fight for his adopted country in World War One, but was too old, at 49, to enlist. Instead, he documented its horrors in a powerful series of prints. Such political work was rare in his ‘mature’ period. La Revue blanche had closed down in 1903, and after his marriage in 1899 to Gabrielle Rodrigues-Henriques, the widowed daughter of the art dealer Alexandre Bernheim, he was financially secure enough to be able to focus on painting.

Critics and historians have lamented this shift because Vallotton was a terrifically innovative printmaker, largely responsible for the revival of the woodcut (Gauguin was close on his heels). Unlike many of his French colleagues, such as Bonnard, Vuillard and Toulouse-Lautrec, who worked with professional printers, Vallotton carved his own blocks and pulled his own prints. He was a natural, combining the aesthetic elegance and abstraction of Japanese models with the experimental freedom and playful spirit of the Nabis. His prints have something of Daumier’s comedic intuition but Vallotton’s humour was several shades darker.

The RA exhibition presents Vallotton as a ‘painter of disquiet’, a description best suited to the psychological tension of his interiors and the chilled eroticism of his nudes. The dark comedy and social charge of his street scenes need a different noun: ‘disquiet’ tamps down Vallotton’s humour and political anger. It also sidelines his prints, which the exhibition itself does not. He had a brilliant pictorial wit, not just sardonic and sharp, as is often remarked, but full of sympathy. Look for the terror-struck, corpulent bourgeois failing to keep up with a crowd that is being chased by the police (The Demonstration, 1893); the nude holding a tiny black dog inches away from her groin (Bathing on a Summer Evening, 1892-93); the polar bear rug staring out at us from an adulterer’s bedroom like a startled witness (The Other’s Health, 1898); the toddler fiendishly ripping and scattering paper on the floor (The Red Room, Etretat, 1899); or the schoolchildren portrayed as roving, belligerent gangs.

His work has always presented a problem of tone, and this perhaps more than anything else – his Swiss origins, his wholesale rejection of Impressionism – has made him a mysterious and marginal figure. The writer and publisher Octave Uzanne called his approach to modern street life ‘vaguely ironising’, hinting at how difficult he is to pin down. But his ambivalence resonated: Octave Mirbeau defended Vallotton’s pessimism against charges of aggression and arbitrary negativity, describing it as a pessimism in sincere search of the truth.

The problem of tone is also a problem of politics. Like Seurat, Vallotton associated with anarchists such as Félix Fénéon, but never described himself or his work explicitly as such. (One of his most famous woodcuts, The Anarchist, captures this ambivalence.) He was a laconic man: his early letters home are brief, not much more than worries about money and ‘please send more chocolate.’ We know very little about his inner life. But his street scenes are alive with political tension and his interiors poke holes in the moral façade of the bourgeoisie.

The rarely seen triptych The Bon Marché Department Store (1898) is a triumph of the exhibition. In a characteristically self-critical gesture, Vallotton implicates himself: a placard in the central panel advertising ‘Jewellery and Objets d’Art’ addresses the viewer, the consumer of his pictures, inviting us to see ourselves as part of the crowd and his paintings as luxury products. Zola described the department store as a modern ‘cathedral of commerce’, a temple of leisure, with shopping the new sacred rite. (At the Royal Academy the triptych hangs across from Bathing on a Summer Evening, a radical reimagining of the fountain of youth as a public swimming pool, to underscore the point.) Vallotton makes the crowd his protagonist, but the left-hand panel depicts an exchange between a man and a woman, presumably salesman and client. Surrounded by soaps and perfumes, their appraisal of lipsticks is unnervingly intimate – hands touching, heads bowed in mock-pious contemplation. A woodcut of the Bon Marché hung nearby shows a similar scene of flirting and shopping, but in stark black and white: a mating ritual corrupted by the drive to make a sale. The exhibition’s arrangement emphasises the interplay between printmaking and painting that defined Vallotton’s early career and suggests connections between the psychosexually charged interiors and the more political urban scenes.

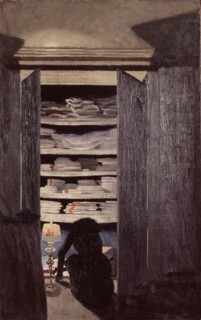

Vallotton liked to position his viewers as semi-detached onlookers, even voyeurs. Uzanne wrote that he captured the ‘bulimic curiosity’ of people in the streets, always on the lookout for spectacles to consume. In many of his interiors, both paintings and prints, he invites us to invade a fraught private moment, almost always between a man and a woman: a quarrel, a disappointment, an assignation. In others, we simply sneak up on someone from behind. This is the set-up in Woman Searching through a Cupboard (1901) and Interior with Woman in Red (1903), both of which show Vallotton’s wife, Gabrielle.

In Woman Searching through a Cupboard, what appears to be a mundane domestic moment is made mysterious by the lamp on the floor, which illuminates the nocturnal scene. Gabrielle has crouched down to examine (to read?) something: her head is bent and we see only her black silhouette, in contrast to the glowing lampshade beside her, painted with colourful boats (Vallotton decorated it for her as a gift). Only the merest hint of the object she was searching for is visible: the edges of two boxes stacked on the cupboard floor. We are led to wonder what secrets they contain. This was the first painting Vallotton exhibited in London, in 1913; it is now, like much of his work, in a Swiss private collection. It’s worth the price of admission to see this alone.

In Interior with Woman in Red, we are positioned (again) a few feet behind Gabrielle, watching her gaze through a series of rooms littered with discarded clothes. This view from behind is also at play in an earlier work, The Sick Girl (1892): we see only the girl’s neck and shoulders as she sits up in bed, but they give us a visceral sense of her discomfort and ennui. Vallotton’s voyeurism is distinct from Degas’s, whose scenes of women bathing or lounging in brothels are charged with physicality. With Degas we are voyeurs of women’s bodies, or (to put it more generously) of women unselfconsciously using and tending to their bodies. With Vallotton, we try to know their minds. The tremendous challenge of such an aim – especially for visual art – is the reason mood and motivation are often unclear. Perhaps it is also the reason that his nudes are usually disappointing, especially at large scale. They abandon psychological subtlety for too much malformed, cold-blooded flesh. Thankfully, there are only a few nudes in this exhibition, and at least one of them is worthwhile: a startling remake of Manet’s Olympia entitled The White and the Black (1913), which turns the racial tensions of the original on their head.

In 1903, the same year the Nabis disbanded and La Revue blanche ceased publication, the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune put on a double exhibition, Vallotton and Vuillard. Vallotton displayed 75 paintings to Vuillard’s ten, making the most of his familial advantage in the first major show of his career. Such a lopsided display couldn’t have been good for their friendship, but they remained close. Vallotton kept a diary during and after the war; it makes clear how much Vuillard’s ‘equilibrium’, ‘tenderness’ and ‘nourishing chatter’ sustained him, tempering his self-diagnosed bitterness and neurasthenia. These late reflections read like torrents of emotion by Vallotton’s standards, but his reserve peels away if you look long enough at the work.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.