Florine Stettheimer was a rich New Yorker who found artistic inspiration in Europe, like a Henry James heroine, looking at Old Masters and Rococo interiors. One of her early paintings riffs on Botticelli’s Primavera: Stettheimer thought his Flora was ‘too fat to move’. Her Spring (1907) shows a slim, nonchalant woman in a powdered wig, flutter sleeves and high heels, attended by squirrels and ferrets and showing a lot of leg. ‘My Flora is kitsch,’ Stettheimer declared. ‘Kitsch’ and ‘camp’ are terms that have troubled her reputation ever since, along with ‘feminine’, though she herself didn’t reject them. Her portraits, conversation pieces and allegories offer a view of New York high society at an intersection with the avant-garde. She wrote poems and designed furniture, theatrical costumes and sets; she was a society lady, an art-world insider, a Proust fanatic and a New Woman. At her funeral, Georgia O’Keeffe said: ‘Florine made no concessions of any kind to any person or situation.’ But she was also great fun. When she finished a painting, she gave it a tea party, inviting a (carefully curated) collection of guests.

Writing about Stettheimer in 1980, Linda Nochlin called her a ‘Rococo subversive’. It might have seemed like a joke, but she meant it. Barbara Bloemink’s new biography continues in Nochlin’s provocative spirit. According to Bloemink, Stettheimer was a social documentarian whose work looks wryly at class, gender, religion and race in early 20th-century America. She makes a compelling case. Stettheimer was born in 1871 to German-Jewish parents who belonged to New York’s One Hundred Families. Her father disappeared when she was seven, but her mother’s money was more than enough to support Florine and her four siblings. The family moved back and forth between Europe and New York: Stettheimer trained as an artist in Germany and then at the Arts Students League in New York, where women were allowed to work directly from nude male models, a controversial practice at the time.

Stettheimer was present for some of the formative events in modern art. She saw Cubist paintings at the 1912 Salon d’Automne before her American peers were introduced to them at the Armory Show in New York. She saw Nijinsky perform L’Après-midi d’un faune in Paris just days after its premiere. She resolved to design her own ballet, with libretto, for Diaghilev’s troupe. Her Orpheus of the Four Arts was inspired by the wild carnival parades put on by art students in Paris in the early 1890s. The never realised designs survive in fairy-tale maquettes and bas-reliefs of dancing figures, made of oil paint, cellophane (a recent invention), chiffon, metallic lace, beads, fur and hair. Stettheimer later described the project, half-ironically, as ‘a means of getting away from the war – like the Greeks invented their gay mythology to make life possible for their melancholy dispositions.’ In September 1914, aged 43, she set sail for New York with her mother and her two unmarried sisters to settle for good.

Florine never married and continued to live with her mother and sisters: Carrie, whose elaborate doll’s house is still a popular attraction at the Museum of the City of New York, and Ettie, the family intellectual, who had a PhD in philosophy from Freiburg. Carrie filled the doll’s house with handmade period furnishings and miniatures of contemporary paintings, including a three-inch version of Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912) made by Duchamp himself. Ettie published two novels with feminist themes under the pen name Henrie Waste (her full name was Henrietta Walter Stettheimer). Both were panned in the press. Bloemink portrays Ettie as envious and increasingly embittered, a conflicted steward of Florine’s legacy. She edited her sister’s diary with a heavy hand, removing passages she considered too damaging or private.

The edited diary offers glimpses of Florine’s personal life. In the early days of an extended romance with the handsome scion of a New York investment bank, she complains that ‘he does not treat me en artiste … still I was amused.’ We know nothing about the relationship because Ettie pruned it out – too sexy, perhaps, or too sad. Bloemink laments the cutting, but I wonder whether it didn’t serve Stettheimer well in the end. Ettie, the only Stettheimer who wrote books, may have anticipated what kind of diary would support scholarship worthy of her sister. Rather than seeing her as a bitter prude ripping out pages by the fistful, we might see her as judiciously removing the sex and gossip that have distracted from the work of many female artists – O’Keeffe in particular. Ettie, after all, also saw herself as a New Woman.

The Stetties first made their name in New York as salonnières. After war broke out in Europe, the guests at their West Side apartments included Francis Picabia, Albert Gleizes, Elie Nadelman and the already famous Duchamp, who mixed with American artists, writers, journalists, gallerists, philosophers, actors and dancers. Florine was an observer at these soirées, on the lookout for funny interactions and fashionable clothes she would later reimagine on canvas (she often included herself in the scene, wearing white pantaloons and red high heels). Visitors got to see the ornate painted furniture Florine designed. She decorated her studio overlooking Bryant Park with a complete set of original furnishings, crystal flowers, cellophane curtains and a shrine to George Washington (‘He is the only man I collect’). Like much of her work, her interior design was grand in concept and technically complex but didn’t take itself too seriously. She conjured a European aristocratic past out of flashy, ersatz materials and Americana. One visitor called her style ‘prickly baroque’.

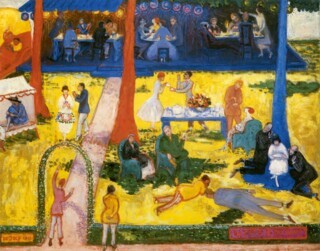

Duchamp was the sisters’ favourite guest. In 1917 they threw an elaborate thirtieth birthday party for him at their summer house in Westchester County. Stettheimer painted it as a group portrait of the Greenwich Village avant-garde transplanted to a Tarrytown estate. Duchamp and Picabia are shown arriving in a red sports car; Henri Pierre-Roché lies face-down, spread-eagled on the grass; the collector Leo Stein crouches with his ear trumpet to hear Ettie, who is reading aloud from a book. Although Florine spoke and wrote French fluently, she paid Duchamp $2 an hour to give her lessons – a discreet form of support. He sketched her in 1925 looking like a flapper who isn’t having a good time. In return, she painted five portraits of him, including one that juxtaposes his two personas: the artist-entrepreneur in jacket and tie, fiddling with a metal contraption that jacks up his feminised alter-ego, Rrose Sélavy. The painting survives in its original frame, with the carved initials ‘MD’ glued like appliqué around the edge. Bloemink believes Stettheimer may have been the inspiration for Rrose Sélavy’s androgynous look. There is no evidence for this, but in the painting Stettheimer does give Rrose some of her own features. In all these reciprocal portraits, gender invites performance and play. Duchamp called Stettheimer a ‘bachelor’, while she and her sisters nicknamed him ‘Duche’.

Other artists and critics saw Stettheimer differently. In an essay published in 1931, the American painter and poet Marsden Hartley describes her work as ‘ultra-refined … ultra-lyrical … ultra-feminine’. These aren’t intended as compliments, but his essay remains one of the most incisive analyses of her work. He writes that she offers ‘delectable, social and aesthetic enjoyment’, presenting her circle ‘under glass … subjected to special heats, special rays of light, special vapours’. Acknowledging her paintings’ ‘clairvoyant veracity’ and ‘hypersensitised charm’, he nonetheless dislikes the ‘refined obscurity’ that ensures they remain ‘the property of special friends’. Hartley was a guest at the Stettheimer salons, and the sisters once helped him out when he was broke. His frustrations with the social conditions of Stettheimer’s work bled into his insistence on its femininity: ‘This woman painter,’ he writes, must be seen in a lineage of ‘women artists’ and ‘feminine expression’. Her ‘delicate satire and iridescent wit’ is something that ‘only a feminine nature can express’, in contrast with ‘epic painting’, which is ‘sober’ and ‘steps out of the social world’. Stettheimer is a ‘Proustian revealer of quaint conduct’ who ‘paints nothing that she does not know’. What she knows is ‘aristocracy of experience, aristocracy of presentation’ in a narrow slice of New York.

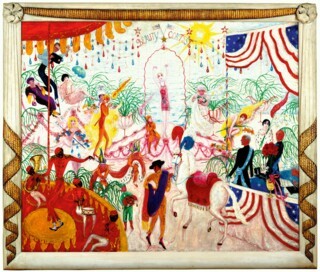

Hartley ultimately declares Stettheimer ‘a master in her own peculiar right’. It is a begrudging canonisation, and I resent how much it corresponds to my initial reaction to her work. It is hard to weigh Hartley’s class-based critique given the sexism that inflects it, but it’s equally hard not to feel implicated in modernism’s sexism when assessing her. Stettheimer invited and deflected her categorisation as a woman artist by painting stereotypically feminine subjects with a cutting wit. Satires of beauty pageants, department store sales, bathhouses and her own family were opportunities to poke fun at savage competitions between women. In Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P.T. Barnum (1924), the pageant is a dystopian circus decked out with enormous fake flowers and American flags. Edward Steichen, the photographer for Vogue and Vanity Fair, shoots glassy-eyed beauties with his big-box camera. One of the contestants, a childlike blonde, wears a white dress patterned with red swastikas (Stettheimer paid close attention to what was happening in Europe). Her bridal veil and bouquet suggest an analogy between Nazism, American standards of beauty and the institution of marriage.

Stettheimer’s poems, which Ettie published posthumously, have a similar edge. She heckles ‘men painters’ for their reliance on female models: ‘must one have models forever/nude ones/draped ones/costumed ones.’ ‘To a Gentleman Friend’ begins: ‘You fooled me you little floating worm.’ An apostrophe to men describes the feminine burden, but it can also be read as an artist’s statement:

You are the steady rain

The looked-fors

The must-bes …

We turn rain

Into diamond fringes

Black clouds

Into pink tulle.

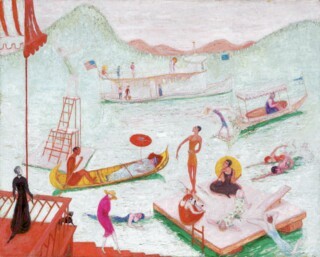

Bloemink draws attention to the darkness behind some of Stettheimer’s candy-coloured scenes. In a series of works that have been dismissed as ‘amusements’ or ‘entertainment pictures’, Stettheimer addressed racial segregation, antisemitism and anti-Catholic bigotry. The subtext of Lake Placid (1919) is the elitism of high-society playgrounds such as the Lake Placid Club, a resort that excluded Jews and Catholics as ‘Objectionable Guests’. Ettie is painted swimming alongside a popular liberal rabbi from Manhattan, while Carrie sits on a raft admiring a svelte man posed on a diving board, Javier Alvarez de Buenavista, then the Peruvian ambassador (and a Catholic).

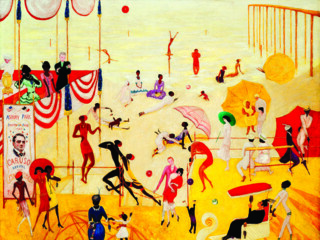

In Asbury Park South (1920), stylish tourists mix with locals at a controversial spot on the Jersey Shore. Stettheimer visited the area with Duchamp and several other friends in the summer of 1920, and they appear as isolated white figures in the mostly African American crowd. People strut, preen, pose, chat and lounge in the sand; decorations indicate that it’s the Fourth of July. In the late 19th century, the boardwalk in Asbury Park was staffed by African Americans and Italian Americans, but many of the white visitors objected to the presence of Blacks on the beach. The local population resisted the landowner’s efforts to segregate the beaches by organising ‘indignation meetings’ and ‘wade-ins’, to no avail. By 1890, they were limited to inferior spots such as Asbury Park South, and the town was often referred to in debates about ‘separate but equal’ laws. Bloemink argues that Stettheimer’s painting is a ‘jubilant and celebratory’ picture of a Black community, but it’s not clear that Stettheimer was making a stand for racial equality. Was she truly ‘subversive’, as Nochlin wrote, or just fashionably provocative and progressive? What is clear is that Stettheimer shows fashion and money as the tools of social posturing across lines of race.

Stettheimer’s greatest success was the series of designs she made for Four Saints in Three Acts (1934), an opera with a score by Virgil Thomson, libretto by Gertrude Stein and choreography by Frederick Ashton. Thomson said he chose Stettheimer because her aesthetic was ‘high camp, and high camp is the only thing you can do with a religious subject … The world of tinsel can only be sincere.’ This misunderstands Stettheimer, who kept an ironic distance from the world she observed. The opera was set in 16th-century Spain but was performed by an all-Black cast – ‘a purely musical desideratum’, according to Thomson. What it lacked in plot it made up for in spectacle. Critics praised Stettheimer’s cellophane backdrops, feather palm trees and colourful silk and lace costumes; they were ‘baroquely witty’, one reviewer wrote, with ‘a gorgeous richness of effect’. The production was a hit, drawing huge crowds first at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, then on Broadway, and finally in Chicago.

Bloemink also gives space to Stettheimer’s Cathedrals, four large-scale allegories of American culture and commerce now owned by the Met: Cathedrals of Broadway (1929), ‘a tribute to the movie theatre as a shining secular shrine’; Cathedrals of Fifth Avenue (1931), a ‘feminist view of marriage as a suffocating undertaking’; Cathedrals of Wall Street (1939), an ironic celebration of money’s role in American politics; and The Cathedrals of Art (1942-44), a satirical apotheosis of the New York art world. Modelled on Raphael’s School of Athens and unfinished at the time of her death, Cathedrals of Art illustrates ‘the delicate balance of power, competition and interdependence’ between the Met, MoMA and the Whitney at a time when various mergers were on the table. Both MoMA and the Whitney were founded by patrons frustrated by the Met’s lack of interest in contemporary art (major gifts and loans were flatly refused). Once they were established, however, the Met wanted to absorb them, and secret negotiations ensued.

Stettheimer’s painting imagines such a merger in the Met’s Great Hall, with museum directors, trustees, critics and dealers (her ‘victims’, as she called them) lining the grand staircase. A naked baby appears as a symbol of contemporary art: at the foot of the stairs, a photographer (George Platt Lynes) zaps the scribbling infant with flashbulbs; on the balcony labelled ‘Museum of Modern Art’, the baby plays hopscotch on a Mondrian, surrounded by Picassos; and at the top of the stairs, the Met’s director tries to give the baby a tour. Bloemink describes the painting as ‘a portrait of art-world infighting’ and a satire on the low status of American art, with Stettheimer herself waving blithely to the viewer like a patron saint in the lower right corner.

But where did she actually stand? One of her poems describes museums as private clubs she has no wish to join: ‘In the Mus-e-um/The Directors drink Rum/For Art is dumb/In the Mus-e-um.’ She had a point, of course, but it is an odd criticism from someone who presented her work at house parties. Did she think her art (or anyone’s) could go straight from the studio to the Met?

Unlike Warhol, who called her ‘my favourite artist’ and, amusingly, ‘a wealthy primitive painter’, Stettheimer was uncomfortable with the public aspects of an artistic career. And she could always afford to make ‘no concessions of any kind to any person or situation’. Aged 45, she had her first solo show at the Knoedler Gallery, but it was a critical failure and nothing sold. She never agreed to a solo exhibition again. She did, however, lend her work to many group exhibitions, especially those at prestigious venues in New York and Paris. The photographer and art impresario Alfred Stieglitz asked repeatedly to show her work at his Intimate Gallery, which opened in 1925. She was, he said, the essential seventh artist in his stable, belonging with John Marin, Arthur Dove, Paul Strand, Charles Demuth, Hartley and O’Keeffe. O’Keeffe pitched in too, writing to Stettheimer: ‘I wish you would become ordinary like the rest of us and show your paintings this year!’ But Stettheimer wasn’t ordinary when it came to money, and her sensibility was nothing like theirs.

In 1930, Stieglitz offered Stettheimer a solo show at his new gallery, An American Place. Once again she declined, saying she was ‘paralysed into inaction’ and ‘indifferent to a public’. She was similarly evasive when asked to sell one of her paintings, or else would quote an impossibly high price. It’s hard to know whether this was prompted by a fear of failure, a dislike for commerce or simply an emotional attachment to her work – the abridged diary gives no clue. The posthumous distribution of her paintings to universities and museums (Columbia received the largest bequest) means that, with rare exceptions, she continues to avoid the market. Outside New York, she has remained largely sheltered from view.

Soon after Stettheimer’s death in 1944, Duchamp set to work organising an exhibition of her pictures, the only major show of another artist’s work he curated. Promoting it in 1946, he called Stettheimer ‘a New York painter … who helped build up the “school” of New York’, painting the city’s art scene and contributing to it as a salonnière. Jackson Pollock made his first drip painting the same year, and the New York School became synonymous with Abstract Expressionism. It’s hard to imagine two more different artists. MoMA’s press release for the Stettheimer show described her as ‘an artist almost unknown to the public yet for decades famous and enthusiastically appreciated in a small circle … The artist wanted it that way.’ When the new, expanded MoMA opened in 2019, it included a small, select gallery dedicated to ‘Florine Stettheimer and Company’, including works by Hannah Höch, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Duchamp and others. She’s still getting her way.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.