Suzanne Valadon appears in several paintings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In The Hangover (1887-89) and Young Woman at a Table (1887), she is shown wearing a crinkled blouse and slumped over a small table, her mouth curled down in weariness or disdain. She was 21 or 22, and trying to make the leap from broke model to respectable artist. Born Marie-Clémentine Valadon in 1865, in a village near Limoges, she was raised in poverty by her mother. While she was still young they moved to Paris, to the working-class neighbourhood of Montmartre (since 1961, the square at the base of the Sacré Coeur funicular has been known as Place Suzanne-Valadon). At eighteen, she had a son. Maurice Utrillo became one of the famous painters of Montmartre, and his career has often overshadowed her own.

From the age of ten, Valadon took almost any job she could get: laundress, dressmaker’s apprentice, waitress, nanny, circus performer. As an artist’s model she used the name Maria, treating the job as the performance it was. Most of the painters she sat for belonged to the Montmartre avant-garde, but she also posed for more established types such as Puvis de Chavannes. She later recalled spending ‘many peaceful hours’ in his suburban studio in Neuilly, posing for a range of figures – female and male, adult and child – in his neoclassical scenes. After each day’s work they walked back to Place Pigalle together. Puvis chattered non-stop. ‘He intimidated me,’ Valadon later said. ‘I never dared confess to him that I was trying to draw, me who from the age of nine had been covering with sketches any paper that came to hand.’

Long afterwards, the prime minister Édouard Herriot praised her as a self-taught wonder: ‘No education at the École, no teacher. Pure instinct.’ Only the first statement is true. Valadon took lessons by watching Puvis, Lautrec, Renoir and others at work, noting their materials, techniques and process, their props and sources of inspiration, their mistakes and revisions. She was matter of fact about it: ‘I took the best of them, their teachings, their examples. I found myself, I made myself, and I said what I had to say.’

Maria became Suzanne when Valadon was in her mid-twenties. ‘Suzanne’ came from a nickname given to her by Lautrec: her modelling for much older men reminded him of Susanna and the Elders (Lautrec himself was only a year older than her). He liked to tease. One of his paintings of Valadon, sitting naked in a huge armchair, is entitled Big Maria – a joke at her expense (she was only five feet tall) and his (she was taller than him). Lautrec might have been the only artist to paint her who also encouraged her to paint, but Degas, who did not use her as a model, was a more enduring fan. He first saw her in one of Lautrec’s drawings, and soon afterwards found her on his doorstep with her own drawings and a letter of introduction from the artist Albert Bartholomé. ‘You’re one of us,’ he told her. Was it a royal ‘us’? Did he mean ‘we artists’? Avant-gardists? Maybe, but it was also a statement about class. This was the greatest gulf between Valadon and Degas (and Bartholomé and Lautrec). The other woman Degas championed, Mary Cassatt, came from a family of bankers, much like his own. I doubt he ever said ‘you’re one of us’ to her.

Valadon visited Degas almost daily. One of her drawings hung in his dining room. Degas admired her nerve, and called her ‘terrible Maria’. Her drawings, he told her, were ‘harsh and supple’ – not unlike his own. Unlike Cassatt or Berthe Morisot, Valadon was free to be harsh: she drank, smoked, and danced in nightclubs with Lautrec and his friends. She painted male and female nudes. Like Degas, she was intrigued by the female body in ungainly positions, especially bathing and grooming. After the Bath (1908), a pastel drawing, shows her strength with colour and line: flesh sculpted with thick black lines against zones of brilliant Prussian blue, lilac, rusty orange and white. The arc of the woman’s right hip is extended to echo the curving arm of the chair she’s kneeling on, so that the right half of her body appears dislocated from the left, the two sides hinged together by a scoliotic spine. Valadon liked sharp elbows, jutting shoulder blades, knobbly knees and abdominal folds, but her figures are also shaped by her knowledge of the strain of holding a challenging pose. She was once that model, hip jutting, back aching.

In 1894, the same year that Valadon met Degas, she moved in with a businessman called Paul Mousis, which allowed her to stop modelling and make art full-time. They eventually married but divorced in 1910, after which she redoubled her efforts to sell her paintings. It took until the 1920s for Valadon to arrive. She was almost sixty, but she at last had the attention of important critics. Major monographs were published on her work and she was offered a contract with the prestigious Galerie Bernheim-Jeune. She wasn’t allowed to forget her lowly origins, however, or her gender. In 1922, the art historian Pierre du Colombier wrote that she had ‘a commoner’s sensitivity’, along with ‘a woman’s meanness, agitated and in spite of itself, sensitive’. Herriot, meeting her at her château in Saint-Bernard, near Lyon, when she was 66, described watching her draw ‘like a child left in a small room by a hard-working mother’.

A few years ago I tried to persuade a curator to put on a Valadon exhibition. Valadon isn’t good enough, she said. What she meant, I suspect, was that Valadon isn’t ‘great’. A good deal of institutional infrastructure and marketing surrounds that notion. But even if one accepts the judgment, that doesn’t mean Valadon’s work isn’t extraordinary. The recent exhibition Berthe Morisot: Woman Impressionist, curated by Sylvie Patrie and Nicole R. Myers, presented a more innovative and virtuosic Morisot than many of us knew. Valadon has been given similar curatorial attention in Suzanne Valadon: Rebel, Painter, Model, which went on display at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia last year and is now at the Glyptoteket in Copenhagen (until 31 July). It is the first major solo exhibition she has been accorded outside France and Switzerland. The catalogue, edited by Nancy Ireson, includes essays on Valadon’s life, work and legacy, as well as a careful biography by Marianne Le Morvan and English translations of primary sources on Valadon and her reception (Paul Holberton, £35).

Her work, which spans five decades, is uneven, but the curation is considered. A small opening section shows Valadon-as-model, with paintings by Santiago Rusiñol, Gustav Wertheimer and Lautrec. The exhibition then proceeds chronologically and thematically: portraits, a few landscapes and still lifes, a number of nudes. The curators make much of Valadon’s nudes in part because they tie her painting most directly to her modelling. She drew on that experience as inspiration, and models, as well as the effort and performance of modelling, are a prominent theme in her work. Several of the nudes are formidable, in particular Nude on a Red Sofa (1920), but her portraits are better. Even fully dressed, her figures express so much of themselves through their bodies. In Marie Coca and Her Daughter (1913), Valadon’s niece, Marie, sits in a plush brown armchair with her young daughter, Gilberte, at her feet. Gilberte, dressed for the occasion, stares straight ahead, stroking the head of her doll. Marie is glassy-eyed, withholding; Gilberte is matter-of-fact, resolute. Gilberte cups the doll’s head in her hand, as if claiming a physical intimacy that she doesn’t have with her mother (Valadon later described the picture as her Madame Bovary).

As in After the Bath, Valadon wrenches the figures into painful contortions: hips and knees out of alignment, spines compressed, ankles tightly crossed. A picture of ballerinas appears on the wall in homage to Degas, who loved this picture-within-a-picture motif. Here Valadon uses it to expose portraiture as a performance and to suggest the physical toll of female roles, especially motherhood. The architecture of the room, plunging down to the left of the canvas, forces the torque of Marie’s body away from Gilberte. One of two superimposed vases of flowers echoes the shapes and tones of their clothes (navy, black and white, with curving, scalloped edges), while the other mirrors the floral armchair. Like their human counterparts, the first vase is positioned against the second, but the flowers are fresher and just out of reach.

Renoir’s son, Jean, remembered that his father wanted models ‘to lapse into a state of mindlessness, to sink into the void’. Valadon gives us the void and the effort behind it. As Martha Lucy discusses in her catalogue essay, Valadon used her own experience as a model to help her capture the stiffening of bodies into painting. Manet’s pictures of his favourite model, Victorine Meurent (of Olympia and Déjeuner sur l’herbe, among other works), have this frisson, but without the experience of someone who, as Lucy puts it, worked on ‘both sides of the easel’.

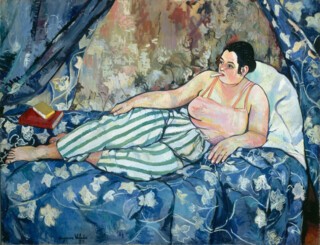

Valadon’s answer to the image of bourgeois motherhood offered up in Marie Coca is her showstopper, The Blue Room (1923). Her model is an anti-model, a woman who is posed as not posing, who might tolerate our gaze but gives away nothing. She lies on a bed, wearing a pink camisole and green-striped pants and smoking a cigarette. Books are piled up at her feet and richly patterned fabrics – including a fashionable asiatique example – frame her like theatre curtains. With her strong hands and simple clothes, her cheeks and décolleté pink from the sun, she appears to be a working-class woman relaxing at home – a reclamation of the harem girl, an anti-odalisque in pyjamas (with a drawstring waist!). The artist Lisa Brice reads her relaxation as ‘a radical act’, an elision of painter and model. Does it make a difference if we know that Valadon was a smoker and a reader?

The Blue Room isn’t a personal painting as much as an art historical one, Valadon’s response to a century of French female nudes: riffing on Ingres’s Grande Odalisque (1814), Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Matisse’s Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) (1907), as well as Félix Vallotton’s response to Olympia, The White and the Black (1913) – all paintings Valadon knew. She substitutes a cigarette for Ingres’s hookah and trades his sumptuous blue silk for a modern print. She merges into one figure Vallotton’s supine white nude and the Black attendant smoking on the edge of the bed. And she takes Matisse’s bold outlines, his hyperbolic curves and exotic setting, and brings them into a private interior, an extension of the figure’s self-expression. As Brice notes, the sensuality of Valadon’s lounger is ‘startlingly contemporary’. It is the casual, easy volupté of everyday life, entirely her own.

Near The Blue Room in the Barnes installation there were two paintings from a series of five depicting a Black model, all dated 1919. In the catalogue, curators and art historians debate the aesthetic and political merits of these paintings, which are rare examples of full-length Black nudes. Ebonie Pollock and Denise Murrell point to the First Pan-African Congress, held in Paris in February 1919, which may have inspired Valadon’s series. Adrienne Childs notes the vogue for jazz (especially in Montmartre) and the prominence of Black performers. Valadon’s Black Venus (her own title) predates the rise of Josephine Baker, and imagines a woman outside this cultural milieu, but it was painted in a neighbourhood that was becoming more racially diverse. This figure, with her confrontational stare, her contrapposto stance and Venus pudica pose, merges a brazenly modern woman and a classical nude. As Murrell notes, this painting and its pendant, Seated Woman Holding an Apple, are yet another response to Manet and his model Meurent, putting the Black model centre stage.

Also noteworthy are the self-portraits, several of which appear in the show. One from 1911 shows Valadon staring herself down, palette in hand. Two houseplants climb the wall behind her. The contrast of reds and yellows against a feast of greens – pastel, forest, emerald, electric – and the proto-abstraction of organic forms, including bodily curves, recall Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings. It would be easy to see this as Valadon’s attempt to turn the ‘Gauguin problem’ of exploitative artist-model relationships on its head. But it is unlikely to have been a motivation. Two years earlier Valadon had begun an affair with her son’s best friend, André Utter, who, while an adult (unlike some of Gauguin’s models), was twenty years her junior. The year they got together Valadon painted a nude double portrait of herself and Utter as Adam and Eve. She plucks the apple as he grasps her wrist; it’s not clear whether he is trying to help her or stop her. She looks radiant and at ease, while he is tense, hollow-eyed, his feet angled away from hers. This detail, which recalls Marie Coca, is deliberate: in two surviving preparatory drawings the pair’s hips sway in the same direction and their feet are almost parallel. The sexual candour and bold colours are characteristic of Valadon. The fig leaves she was forced to add to make the painting acceptable for public exhibition are not.

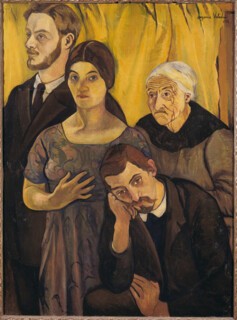

Valadon’s paintings and drawings of her son, from childhood to adulthood, are among the strongest works in the exhibition: sure-handed sketches of a languid boy, napping or fresh from the bath; a portrait, Grandmother and Grandson (1910), in which Maurice sits with Suzanne’s mother and their dog; a Freudian Family Portrait (1912) with Suzanne standing between Maurice, who looks miserable, and Utter. Her mother stares through this vicariously incestuous trio, while Suzanne looks out at the viewer and gestures to her breast, acknowledging herself as the source of strife and the one who holds this family romance together. Best of all is a portrait of Maurice painted in 1921, when he was 37. Valadon has given him her wide brows and dark auburn hair – in the painting at any rate – and he sits at an easel, scrutinising his mother. Is there another example of an artist painting her son painting her, of self-portraiture’s mirrored gaze refracted through the artist’s offspring? Here Valadon reimagines the mother and child motif, prying the two apart but not releasing the intimate connection. A child is a kind of mirror, after all, and sometimes more difficult to face than a piece of glass.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.