The great American film directors have suffered from a common predicament. Democratic fealty and, more important, financial constraint meant they were bound to respect popular taste. That requirement need not have been oppressive – silent movies, after all, were descendants of the popular fiction of Balzac and Dickens. What dampened the spirits of all but the most cunning veterans was the incessant pressure to follow a proven formula – which actor was bankable, what story might attract or offend which particular audience. And ultimately there was no choice. An original like Howard Hawks could defy the odds with Scarface and His Girl Friday, but a personal ‘signature’, too, becomes a formula in the end, and Red River gives way to Rio Bravo and Rio Lobo. To step seriously out of the groove of the big studios condemned a director to failure and the posthumous honour of indie renown. The largest exception to the rule, as Robert Kolker and Nathan Abrams show in Kubrick: An Odyssey, owed his escape to a coalescence of luck and preternatural self-confidence.

Kubrick is a comprehensive Life. It yields, in orderly procession, almost every fact a scholar or a fan might want; and a fair number of motifs are traced between one film and another, and between Kubrick’s experience and what went into his films. For the last thirty years of his life he was a cult, dense in formation and resistant to external view. As an episodic (non-dues-paying) member, I have now read, in addition to the biography, the full-length critical studies by David Mikics and James Naremore, watched Jan Harlan’s excellent documentary, Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures, and explored every entry in The Stanley Kubrick Archives edited by Alison Castle: a 13-pound art-historical tome containing solid articles on every Kubrick film, together with miscellaneous interviews, excerpts from published memoirs and reviews, and photographs taken on and off the set. It may be a close call for non-initiates, but I think the trip is worth the expense. Aficionados tend to divide between two touchstones, Dr Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey. I belong to the first group but can see the point of the second: which way you go may depend on the affinities that separate physics and metaphysics. As a speculative romance about the way human life could find rebirth and transformation, 2001 was a natural successor to the black and white projection of the way this world would end. Dr Strangelove was still showing in second-run theatres soon after I learned about the effects just one hydrogen bomb would have, but what struck me then was not the political warning so much as the strange credibility of the parallel outdoor and indoor journeys that shape the story: the fatal progress of the B-52 over the Arctic wastes, and the protocols obeyed and decisions taken by the president and the joint chiefs of staff in the darkened war room.

Stanley Kubrick was born in the Bronx in 1928, the son of a successful neighbourhood doctor. Jack Kubrick and his wife, Gertrude, were literate secular Jews; there were plenty of books around the house, and Jack owned a 16 mm camera suitable for home movies. For his thirteenth birthday, instead of a bar mitzvah, Stanley received a Graflex Speed Graphic camera: a model favoured at the time by press photographers. In school, he did well in science but was bored by most of the assigned reading, and his prospects for college were sunk by a cumulative average of 67. The disappointment mattered less than it might have done: by his senior year, Kubrick had begun placing photographs in Look magazine. A regular position there would support him over the next four years, and from travel and miscellaneous assignments he learned a good deal about the way the world worked.

Kubrick’s photographs for Look are hard-edged and commanding; they fix an image once and for all. Far from being illustrations, they have a quality – a little like Weegee’s – at once random and composed. In one, the circus director John Ringling North dominates the right half of the frame, shouting instructions to an unseen person, while above and to the left a high-wire act has two showgirls suspended from the wheels of a bicycle: the picture frame is divided by a balancing bar carried by the cyclist. In another, a scientist works with a slab of white-hot metal, shielded from the dazzling light by opaque goggles. Kubrick also photographed celebrities like Montgomery Clift and Rocky Graziano. His aesthetic was realist, no gimmicks allowed, but he never stinted on drama: a news vendor, looking contemplative beside a headline that reads ‘FDR Dead’, was told to look sadder. The vendor complied, and the result was a picture ready to receive the caption ‘A Nation in Mourning’. Kubrick told Jack Nicholson many years later that a photograph is a copy of life, but ‘in movies you don’t try and photograph the reality, you try to photograph the photograph.’ Did this mean that the film is the more real of the two copies by virtue of its conscious abstraction? Reality, he seems to have felt, is an unlisted bottom floor – hard to get to and, once you have got there, hard to the touch.

There was a movie theatre on almost every block in his part of the Bronx, and, as he told Jeremy Bernstein in a 1966 interview, ‘I used to go to see films … practically every film.’ Art-house theatres scarcely existed yet, but you could buy a ticket to the Museum of Modern Art, where they showed Chaplin, Griffith, Von Stroheim, Eisenstein, Murnau, Pabst, Lang. For the greats of the silent era, Kubrick seems to have felt a veneration free of envy. The typical American product of the 1940s drew a different response: he was sure he could make something better. For Kubrick (according to Michael Herr, his friend and collaborator on the screenplay of Full Metal Jacket), ‘there was definitely such a thing as a bad movie, but there was no movie not worth seeing.’ He told Herr in an exuberant moment that The Godfather must be the greatest movie ever made. When challenged he backed off a little: it was the movie with the greatest cast. This points to a curious fact about Kubrick’s own work with actors. There are magnificent performances in his movies – by George C. Scott, James Mason, Peter Sellers, George Macready, Kirk Douglas, Nicole Kidman, Sterling Hayden; and in smaller roles, Slim Pickens, Peter Ustinov, Sue Lyon, Leonard Rossiter, Shelley Winters, Sydney Pollack – but there is never a trace of ensemble feeling. The actors, and for that matter the characters, are monads, each in a separate cell.

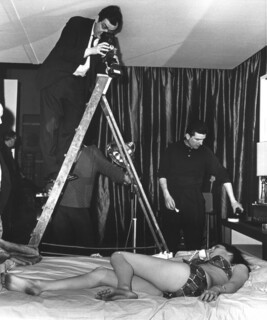

A short documentary, Day of the Fight, was the first film Kubrick sold to a theatrical distributor, in 1951. A sketch of the professional boxer Walter Cartier, his daily life and training regimen, it concluded with the fight itself, recorded blow by blow. It was praised but led to no offers. In his early twenties now, and impatient, Kubrick decided to make a full-length film; the result, the following year, was Fear and Desire, on which ‘the entire crew … consisted of myself as director, lighting, cameraman, operator, administrator, make-up man, wardrobe, hairdresser, prop man, unit chauffeur.’ This thoroughness, a demand for complete control, characterised his approach at all stages of his career. Terry Southern said that Kubrick’s practice of filmmaking ‘starts with the germ of an idea and continues through script, rehearsing, shooting, cutting, music, projection and tax accountants’.

Fear and Desire tells the story of four soldiers on a mission to commandeer a raft, steer it down a river and assassinate an enemy general. The script is grave and poetical; as the narrator explains at the start, it will present ‘not a war that has been fought, nor one that will be, but any war … these soldiers that you see keep our language and our time, but have no other country but the mind.’ The mature Kubrick disclaimed any pride in the film; all it did was teach him how a film was made, and that he could make one. Yet it took nerve. Arriving in the middle of the Korean War, Fear and Desire shunned the slightest hint of uplift. It opened at the Venice Film Festival and was shown at a New York cinema. One might have guessed it was the debut of an avant-garde artist who would return to ‘no other country but the mind’.

Kubrick had different plans. He plotted his next film as a flatly acceptable genre piece. The human drama would provide the barest pretext for excitement delivered in two action scenes: a protracted chase and a hand-to-hand fight. He asked a schoolmate, Howard Sackler, who had drafted the screenplay of Fear and Desire, to work up a script at high speed in order ‘to take advantage of a possibility of getting some money’. The last words are Kubrick’s and they reflect his circumstances in 1955: he was paying his bills with unemployment benefits, augmented by his income from playing chess for quarters in Washington Square. Two or three dollars a day, he said, ‘really goes a long way if you’re not buying anything but food’. In the chase sequence of Killer’s Kiss, the hero, pursued by the killer, runs around the perimeter of an industrial rooftop, hoping to find a way down, while the stationary camera watches him for a long minute: a dwindling speck on the horizon, then growing larger again. The shot makes an image of futility. Soon after comes the fight with the killer in a storeroom. The two men’s weapons include mannequin limbs and torsos, an axe and a halberd.

Killer’s Kiss made an immediate impression on James Harris, a freelance writer and producer. He got in touch with Kubrick; they decided to join forces and together looked to match a project with an investor. Eighty thousand dollars from Harris’s own funds and a $50,000 loan from his father backed up a modest $200,000 from United Artists to finance The Killing, which came out in 1956. (The two men continued as a team for Paths of Glory and Lolita – the best and warmest collaborative relationship of Kubrick’s career.) The action plot of The Killing and the names in the supporting cast, including Marie Windsor and Elisha Cook Jr, place it in the noir cycle of the 1950s, but Kubrick told the story adroitly in flashbacks from overlapping points of view. The result owes something to The Asphalt Jungle, of which it gave an additional reminder by casting Sterling Hayden in the lead, but Kubrick’s film is subtler in its psychology, and an abiding trait emerged distinctly here: this director liked to keep the camera moving without drawing attention to the fact. His exemplar was Max Ophüls, for things like the long tracking shot of James Mason and Barbara Bel Geddes in Caught, dancing in a crowded club, nudged close together and realising that they enjoy it. The credited cinematographer in The Killing, Lucien Ballard, had worked with Josef von Sternberg and Jacques Tourneur, but on the set Kubrick betrayed a total distrust of anyone else controlling the camera. He took charge when he saw the setups Ballard had arranged for the climactic scene in which a horse is killed on a racetrack to divert attention from a robbery: four cameras had been placed at external locations, but none mingled with the crowd to catch the ripples of enthusiasm and shock. It was hopelessly inadequate, and Kubrick appointed a friend to smuggle a hand-held camera onto the track and take the crowd shots. He would always crave verisimilitude. Was there light on the actors’ faces in an indoor night-time scene? You had to know where the light was coming from – the street, the next room, whatever. ‘One time,’ Windsor recalled, ‘when I was sitting on the bed reading a magazine, he came up and said: “I want you to move your eyes when you’re reading.”’

The Killing was a critical success, not a serious money-maker, but Harris-Kubrick resolved to strike again while the iron was hot, and their next movie came out just eighteen months later. One of the few books Kubrick had read with interest in high school was Humphrey Cobb’s Paths of Glory, about a failed attack by the French infantry on a German stronghold in the First World War. It has been said, with justification, that Kubrick’s films show a preoccupation with violence. Yet his interest is of a peculiarly unexcitable kind, whether the action is grinding, as in trench warfare, or sudden and concussive, as in a boxing match or a duel. He is never in it for the spectacle, he never invites the audience to share the thrill of men destroying one another: the feeling is cold, a turn-off. The French general (George Macready) who commands the assault on the German position nicknamed the Anthill – after a show of conscience when he learns that 60 per cent of the men can expect to die – is talked into the mission by his military superior (Adolphe Menjou) with the lure of a promotion. The hero, Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas), marches the length of the trench to lead them, and this happens in an extraordinary tracking shot, one camera facing Dax as he walks forward under the crash of artillery, a second camera facing ahead from his point of view. The shot runs almost two minutes. The first wave of men is met by overpowering bursts of machine-gun fire, shelling and grenades, and when the inevitable retreat ensues, the general commands the French artillery to fire on their own troops. The entire sequence is an education in the process (as Simone Weil said of The Iliad) by which men are turned into things; and the deafening sounds of the battle account for much of the effect. The general orders a hundred of the men who retreated or refused to attack to be shot by a firing squad, then bargains himself down to twelve and finally settles on three: ‘Let’s not haggle.’ A sudden cut: from the end of the court martial straight to the march of the firing squad.

Two anomalies in Kubrick’s conduct on and off the set became unmistakeable in Paths of Glory. He was endlessly painstaking in preparing the set, the lighting, the posture and positioning of actors; and he had no scruple about making the cast and crew wait. The same held true for the number of takes necessary to capture the right version of a scene. Once, in the small hours, around the fortieth take of a scene where he ended up asking for 84, Douglas said they had to break and get some rest, but Kubrick shouted back: ‘It isn’t right – and I’m going to keep doing it until it is right.’ His criticism of actors normally came in the form of a muttered hint, often just ‘Do it again’ – in Kolker and Abrams’s copious record, this is the only instance of Kubrick raising his voice – but the occasion is the more remarkable for that. He was a young director, still in his twenties, Douglas a top-billed actor in his prime, but Kubrick asserted his authority for everyone to hear. His identification with his films was arbitrary, complete and brooked no exception.

The final scene of Paths of Glory gave proof of an intuitive strength. A young German woman is singing ‘Der treue Husar’ – she has been hauled onstage in the nearby pub to entertain the exhausted troops – and the men jeer at first, but one by one their cruelty melts, and they join her and hum the song about love and war whose words they cannot understand. The great scene came from an impulse of Kubrick’s after a misjudged offer of compromise. He had thought to brighten the ending and make it commercially safe by giving the soldiers condemned for cowardice a last-minute reprieve; Douglas, rightly, said no; and Kubrick followed up with an alternative: a German woman singing, the men acting like animals and gradually becoming human. Harris thought the idea was daft, but Kubrick said he had the right person: ‘Let’s shoot the scene, and if you don’t like it, we won’t use it.’ The right person was a German actress, Christiane Susanne (soon to become Christiane Kubrick); he brought her in to close the drama on a montage of the hapless woman and the haggard faces of the men. Paths of Glory is a tremendous film, but it may have conveyed a false idea of Kubrick’s temperament. It was received as an antiwar statement. Two of his next three films, Spartacus and Dr Strangelove, confirmed that impression, and accordingly Kubrick was marked as the welcome successor of the American liberal directors: Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, George Stevens. This goes some way to explaining the confessions of disappointment from liberal reviewers in Kubrick’s last three decades. Starting with 2001: A Space Odyssey, critics said that he had become inhumanly abstract, or misanthropic, or consumed by technique. But the mistake lay in the expectation.

Douglas hired Kubrick again three years later to replace Anthony Mann as the director of Spartacus. This was a risky opportunity; but in 1960 success with a Roman epic could be trusted to make a director’s commercial reputation. An iron law of the genre was that Jesus must be in the movie somewhere. Spartacus dodged that requirement yet answered it by implication: Jesus, like the slave-revolutionist Spartacus, was a rebel against the empire. The crucifixion of Spartacus and his army of slaves could deliver the necessary allusion. Kubrick handled the job like a veteran, and earned the respect of a large professional cast, including Laurence Olivier as the second lead, Crassus. The final cut left Kubrick deeply dissatisfied – he made and kept a vow never again to cede control to a producer or a studio – and he said in interviews that he could take pride only in the gladiatorial sequence. But that section of Spartacus runs for 45 minutes and drives all the sympathy that carries the rest of this three-hour exercise in Super Technirama 70. The other sequence of Spartacus that people tend to remember is the concluding battle outside Rome. This went far beyond Dalton Trumbo’s script. The scene was demanded by Kubrick, scheduled late and had to be shot in Spain, but nothing compares with the shudder of watching the single files of the Roman legions separate and realign like sections of a snake. The extended moment is soundless except for the clatter of armour; and the legions cover the horizon.

Though Kubrick bowed to the studio’s demand for sentimental interlarding – the love scenes between Spartacus and Varinia, the folk dancing of the joyful rebels, like a socialist summer camp in North Hollywood – no one doubted who was in charge from day to day. In directing Spartacus, he again fell out with a cinematographer of high reputation – Russell Metty, who had worked with Orson Welles and Douglas Sirk – and once again he took over entirely, leaving Metty to drink and comment from the sidelines. Kubrick could hardly change the credits, however, and the paranoid punishment fitted the egotistical crime. Spartacus was denied an Oscar nomination for best picture or best director, but the award for best cinematography went to Metty.

All of Kubrick’s movies, after the two he made on a shoestring, are adaptations in the sense that they have a literary source. Unlike Thackeray’s mock romance The Luck of Barry Lyndon or Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle (which became Eyes Wide Shut), Nabokov’s Lolita had a well-known identity as to plot and style. Lolita pushed a non-moral aestheticism to the limit, and tested that limit. The narrator, Humbert Humbert, is a collector of choice sensations and especially of the pubescent girls he calls nymphets. He narrates his own story – ‘You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style’ – and the puzzle for commentators has always been: does he convict himself, or does he charm the reader into an acquittal? Kubrick took these ambiguities off the map. He minimised the first-person narration and transformed the dark comedy into a romantic story of doomed love. He may have been influenced by Lionel Trilling’s review of the novel, but that was an interpretation. The movie had to stand up as a separate work.

Kubrick’s film, released in 1962, threaded the needle wonderfully. An early scene between Humbert and Lolita brings out his delicate feeling for the psychopathology of normal life. Lolita is climbing the stairs to deliver the breakfast on a tray that her mother, Charlotte Haze, has lovingly prepared for their lodger. On entering his room, she puts down the tray and confesses, ‘Don’t tell mom but I ate all your bacon,’ as he slides into a drawer the diary in which his lust for the girl and loathing for her mother have just been confided, a furtive gesture prompting Lolita to ask: ‘What were you writing?’ ‘A poem,’ he lies, ‘about people,’ and she responds with cool sarcasm: ‘A novel subject. You know, it’s funny, it sort of looked like a diary when I came in.’ But Lolita agrees to hear him read a poem by someone else, ‘the divine Edgar’. Nabokov wrote an overlong draft of the screenplay, most of it never used, but his touch is evident in the choice of this trite and mellifluous patch of romantic agony about a lost love: ‘It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,/In the misty mid region of Weir.’ Humbert, connoisseur and pedant, asks Lolita to notice how ‘mid’ echoes and reverses ‘dim’ across the lines; and she agrees, leaning over the desk, munching a slice of toast: ‘Ah, that’s pretty good, pretty clever.’ But when he utters the sonorous refrain ‘Ulalume, Ulalume’ with a sigh of transport, she changes her mind: ‘Well I think it’s a little corny, to tell you the truth.’ He asks an anxious question about one of Lolita’s friends, and she says she knows some things, but ‘You’ll blab’; he promises not to, and she says that deserves a reward; and here, though the mood stays the same, the import changes imperceptibly. She asks him to lean back in his chair – ‘You can have one little bite’ of a fried egg she holds above his open mouth – but he grabs her arm and takes more than allowed. A childish flirtation, on her side, not without an intuition of her charm. And on his side? The movie knows when to cut.

The tone of Kubrick’s Lolita is not like anything of its time, or any other time. It teases, without hiding the pain on both sides; for better or worse, it is a love story. Lolita’s motive in going along with Humbert is to get away from her mother, and she has her chance when Charlotte dies in a freak accident. A free-form satire on American popular culture and middle-class mores is at work in the movie as surely as in the novel. And there is parody of a more internal kind: to learn what Kubrick sounded like in person, you need only listen to the interrogation of Humbert on a hotel patio by his nemesis Clare Quilty. Sly, insinuating and immensely knowledgeable (with a soft Bronx accent), Quilty seems offhand and yet presses every point. Sellers here delivered an auditory photograph of Kubrick. Lolita was named by David Lynch as one of his favourite films, and when the director of Blue Velvet and Mulholland Drive was asked why, he said: ‘It catches something, under there somewhere … it catches hidden things.’

Dr Strangelove began filming three months after the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, but Kubrick’s interest in the danger of a nuclear war went much further back. The turn this film took, from thriller to grim satire, occurred after his immersion in the writings of the defence strategists of the day – Herman Kahn, Thomas Schelling and others. Kahn, in particular, Kubrick admired and had got to know, but he detected a flaw in the mathematical genius who game-theorised the odds of survival in the face of the bomb. Kahn and the others were converting matters of human whim and agency into a logical diagram. Their arguments were aesthetically ingenious, Kubrick thought, but far less credible than the take a real imaginative writer would have on the subject; and he came to think of them as ‘crackpot realists’ (a phrase he borrowed from C. Wright Mills’s pamphlet The Causes of World War Three). Sellers in his several roles, Sterling Hayden as the psychotic general Jack D. Ripper and George C. Scott as the well-meaning Pentagon ‘moderate’ General Buck Turgidson all did some of the best work of their careers, but Kubrick’s approach brought them close to caricature. This effect was deliberate. Kubrick had asked Scott to execute each of his scenes first in a straight realistic take and then in an over-the-top one; and Scott was mortified by Kubrick’s invariable choice of the over-the-top version. But the tone had changed between the script the actors saw and what resulted from Kubrick’s limousine rides to Shepperton Studios, accompanied by Terry Southern. Kubrick had brought in Southern after deciding that his novel The Magic Christian contained ‘certain indications’ of the turn he wanted to give the screenplay. They arrived at a method of showing, by the sedate and heavy-footed presentation of outlandish events, that the ordinary official routines of self-preservation were compatible with the mania of a world-ending catastrophe.

With Dr Strangelove, Kubrick began his practice of using a score comprising existing music. It could work as a signal for the cognoscenti: ‘Try a Little Tenderness’, played over the main titles, as the B-52 is refilled by a tanker plane; or ‘We’ll Meet Again’ sung over the montage of mushroom clouds that ends the film; or the Civil War ballad ‘When Johnny Comes Marching Home’ accompanying the bomber that has slipped under Soviet radar. But his new method could go much further. For 2001, Kubrick would test several dozen recorded versions of the ‘Blue Danube’ waltz before he found the right one for the docking of the ship at the space station; and that film’s opening notes from Also sprach Zarathustra would key the Nietzschean idea of self-overcoming that gives a semblance of coherence to the plot. His use of familiar tunes, and sometimes of recondite classical works, runs parallel to his curious ritual of playing music on the set in the intervals between filming: something he thought helped the actors and crew to grow attuned to one another.

Kubrick’s anthologist-like attention to music also went naturally with his emphasis on the extended scene: a predilection, as time went on, that set him ever more firmly against the preferred fast tempo of montage-based editing. For music, he would take whole pieces or at least integral parts, rather than the opportunistic fractions most movie music was reducible to. So the Dies Irae and its echo in Dvořák’s New World Symphony, teetering into jangle and discord over the main titles of The Shining, would give a legitimate promise and warning of the action to come. The way lay open as well for the reiterative – but inspired and explanatory – use of the slow movement of Schubert’s E flat piano trio in Barry Lyndon; and in Eyes Wide Shut, the Shostakovich jazz waltz to suggest mild erotic temptation and the two-note piano theme of Ligeti’s Musica Ricercata to signal danger and compulsion.

He took a long time over 2001, with many doubts and changes of concept, and the premiere, in April 1968, was disastrous. Many of the invited audience walked out before the end, and Kubrick thought his career might be finished. But that was a New York crowd from ‘the industry’, average age around 55; not for the last time, Kubrick did some late editing; and the film caught on, thanks to the younger crowd it drew on the West Coast and eventually pretty much everywhere. The invention of 2001 was negative: it bypassed the assumptions of a sci-fi thriller by never showing the alien force, even while adopting a story of unexplained effects that left no doubt of its presence. In the quite extensive publicity for the film, Kubrick spoke of the human sense of the loneliness of space which he found pre-eminently in the fiction of Arthur C. Clarke. And the film owes its lasting appeal to that common sensation: we find it almost impossible to believe that we are alone, and impossibly difficult to imagine how we might not be alone. Yet nothing in the spaces between the stars could be scarier than the scene in which the astronauts isolate themselves to discuss their doubts about the computer HAL and, by a sharp edit, we are made to see that HAL can read their lips. It is the greatest purely abstract recognition scene in the history of cinema. It says in a flash, without sound or words: trouble is coming. At the same time, it raises the possibility that machines can have motives just as people do – a conjecture that would fascinate Kubrick to the end of his life. What is still more strange is that people should come to trust machines more than they trust themselves. Kubrick’s stories of love, war and social climbing all in their different ways involve a temptation to eliminate errors and disappointments by a surrender to sheer mechanism.

He had moved to England in 1965, and would remain there, first at Abbots Mead in Hertfordshire, ‘a large, semi-rural family house’ not far from Elstree Studios, and from 1978, with more equipment in need of storage, at Childwickbury Manor, also in Hertfordshire. All the while, he kept up his reading about two subjects he never tired of, the Napoleonic Wars and Nazi Germany. For a long time, he nursed an interest in a biographical film about Napoleon. Sergei Bondarchuk’s 1970 Waterloo, with Rod Steiger, did not deter him, nor did Fielder Cook’s 1972 Eagle in a Cage with John Gielgud. But how many movies could the subject take? It is hard to regret his decision to shelve it. The part of Napoleon would have demanded a major actor of considerable energy, but Kubrick had begun to prefer actors with a flat affect, and his direction flattened them further. This might suit the design of 2001, where the science jock Keir Dullea was set off against the all too human computer. Kubrick would ask for, and get, a similar approximation of non-personality from Ryan O’Neal in Barry Lyndon. But the truth is that his relationship to the very idea of actors was bipolar. Should one use them as mannequins (Robert Bresson’s word for his practice with non-actors), or find good ones and let them tear up the scenery? The latter sort of permissiveness had resulted in Sellers’s work in Lolita and Dr Strangelove and would lead – with more mixed results – to Jack Nicholson’s performance in The Shining. Kubrick’s ambivalence in this matter faced a final test in Eyes Wide Shut. Was Tom Cruise an actor or a mannequin? The star of Top Gun may have been chosen to fit the Dullea-O’Neal type, but Cruise’s ability landed him somewhere in between, and the decision to pair him with Nicole Kidman, an actress to the core, opened the possibility of a mannequin becoming human, which was the point of the hero’s all-night adventure. The same puzzle lay at the heart of Kubrick’s interest in the Pinocchio story. He put in several years of work on a script and storyboards for a film about artificial intelligence. Eventually, he unloaded the AI project on Steven Spielberg; Kubrick himself was posthumously thanked in the credits. The sentimental ending of AI was a predictable outcome that he would never have permitted as director under his own name.

For much of the 1980s and 1990s Kubrick was also considering a film about the Holocaust. The idea was still in his mind when the screenwriter of Eyes Wide Shut, Frederic Raphael, wondered whether Schindler’s List might have satisfied that need. Raphael reports the exchange that followed:

S.K.: Think that was about the Holocaust?

F.R.: Wasn’t it? What else was it about?

S.K.: That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about six million people who get killed. Schindler’s List is about six hundred people who don’t.

No protagonist of a Kubrick movie is ever crowned with success. Colonel Dax in Paths of Glory fails to acquit the soldiers falsely condemned to death for cowardice; Spartacus marches on Rome but is defeated and crucified; Barry Lyndon is forced to leave England and accept an annual income from the stepson who shot off his leg in a duel.

Probably most people remember from A Clockwork Orange (1971) the mascaraed eye of Malcolm McDowell, as Alex the rebel and gang leader, strutting on the banks of the cement riverbed and beating up the tramp and driving hard through the night to rape the artistic-bohemian woman and force her husband to watch – after which he relaxes with his ‘droog’ chums in the Korova Milkbar. It was a nightmare vision of Haight-Ashbury or Chelsea in the late 1960s; and the movie in its oblique way registers Kubrick’s distaste for the hipster criminality that formed a distinct element of 1960s counter-culture. The message of A Clockwork Orange was not pro-violence but anti-state – so plainly so that Kubrick must have felt ambushed when reviewers for the liberal papers called the movie fascist. The eruptive violence of an individual, this movie says, is a terrible thing, but the disciplinary violence of the state is worse. Beneath the avant-garde surface, A Clockwork Orange is a didactic allegory, on-purpose to a fault, and its energy flags and dies early. The long second half comprises the behaviourist cure of Alex by the carceral authorities, and the climax shows him reviving his animal spirits by the usual means: a fantasy of violent sex, triggered by Beethoven’s Ninth; but now his interests have merged with those of the state, and the fantasy incorporates an exhibitionist thrill from being watched by a crowd. No longer a violent rebel, he has become a violent hypocrite – a sociopath in good standing with the authorities. Copycat beatings and killings prompted Kubrick to withdraw the film from British circulation in 1974. It came back only in 2000, the year after his death.

A Clockwork Orange was an oddly undefended mistake. The parodic elements, in the police scenes for example (borrowed from Monty Python), had a crude explicitness that suggested a more fundamental disorientation; and Kubrick would climb back slowly. Barry Lyndon (1975) was a careful first step; but, as with Lolita, adaptation here meant a different work entirely. The Luck of Barry Lyndon is a picaresque novel, stuffed with encounters and anecdotes in the Fielding-Smollett manner, which the screenplay reduces to half a dozen separate settings and big scenes. Thackeray’s hero was an adventurer and a rake who told his own story without a stitch of moral-minded piety. Kubrick rejigged it and altered the rhythm to a death march. A narrator (Michael Hordern) guides the audience with a vaguely Johnsonian approximation of dignified and judicious assessment: ‘Barry was one of those born clever enough at gaining a fortune, but incapable of keeping one. For the qualities and energies which lead a man to achieve the first are often the very cause of his ruin in the latter case.’ The third-person narration here encumbers an easy aside with sententious gravity. Compare the shameless first-person deftness of Thackeray’s Barry: ‘To the lady’s questions regarding my birth and parentage, I replied that I was a young gentleman of large fortune (this was not true; but what is the use of crying bad fish? My dear mother instructed me early in this sort of prudence).’ The daredevil charm would have made him too much like Alex.

Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon pleased many people of general taste because it confirmed their feeling that the 18th century took a long time. Kubrick picked out the gorgeous backgrounds after careful reconnaissance; with his usual studiousness, he had pored over prints by Gainsborough, Reynolds, Joseph Wright of Derby and, most of all, Hogarth. Yet the satirical portraiture – a dandyish French aristocrat with a mistress on either hand to comfort him for losing at cards – often leans on cartoon-strokes that are out of keeping with the sombre intention. Barry, after all, is a casualty of circumstance, led on by an inscrutable will, and as opaque to himself as the hominid in the Dawn of Man prelude of 2001 who suddenly discovers he can murder a larger mammal with a club.

With The Shining, Kubrick turned again to a well-marked genre, horror-gothic, and the film is admirable for its uncanny moments: the sound-before-image bang of the rubber ball in the hotel lobby where the writer Jack Torrance (Nicholson) is bored out of his mind and getting close to an even more dire slump; the shock discovery of the manuscript that proves his madness, page after page of the sentence ‘All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy’; and the tricycle ride by his sensitive child, Danny, in the vacant hotel, along the vast reaches of the floor, around corners that will lead to a place that is not nice at all. The Steadicam, mounted low behind him but creeping forward as he pedals, is a stroke of craft; and when Danny is stopped by the apparition of the dead girls who invite him to play, imagination is given its true importance ahead of panic: his gaze is a compound of fear and curiosity. The Shining was one of the highest-grossing films of 1980, but it also confirmed Kubrick’s reputation for outsize expenditures of time and resources. An average ratio of film shot to final cut was then around 10:1. For The Shining, it was 102:1.

Full Metal Jacket arrived seven years later, a step behind Platoon and other movies about the Vietnam War. Formally, however, Kubrick was inventive to an extent unimagined by his predecessors. The first half submerges the viewer in the ordeal of Marine Basic Training, an experience almost as brutal as the war the men will eventually fight. Kubrick hired a real marine drill sergeant, Lee Ermey, to play the part, and was rewarded by the best performance in the movie. The choice confirmed his old insistence on fidelity to nature. ‘No one can “make up” a tree,’ he said, ‘because every tree has an inherent logic in the way it branches. And I’ve discovered that no one can make up a rock. I found that out in Paths of Glory.’ The literalism went hand in hand with his absorption in problem-solving. Major Kong, in the bomb bay of the B-52, was problem-solving when he fiddled with wires to unlock the door and enable the release. The second half of Full Metal Jacket deals with a single problem-solving mission: to clear out a sniper’s nest in the evacuated city of Hue. The progress of the mission is slow, continuous and terrifying, but Kubrick never quite decided what he thought of the protagonist, Joker (Matthew Modine), and the perpetual half-smile on Joker’s face is an evasion that falls short of irony. Yet the strength of the movie comes from a different kind of refusal. Full Metal Jacket declines to say whether human nature is distorted by war or war itself is an emanation of human nature.

The people who inhabit Kubrick’s films are often abstract, hemmed in by their social functions; yet a great many of them appear ‘born that way’ – stubborn, fully formed and delimited, incorrigible. The gifted Danny, exploring the gigantic hotel on his tricycle, and the German physicist in his wheelchair in Dr Strangelove, calculating the end of the world with a circular slide-rule, differ from the rest of humanity only in their mental abilities, but they also show a hidden passion at work: a disinterested desire to find the truth, to nail it down and map its effects. They want to master the world, a different thing from knowing oneself. There is no hint of an approach to self-knowledge by any character in Kubrick’s films, never a moment when someone learns something. There is, however, a false revelation, drawn out and misleading, at the end of Eyes Wide Shut.

The sinister patron and magus in that movie is the wealthy businessman Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack). He appears first as the generous host of the extravagant Christmas party whose dangers will set Bill Harford on his chase after new sensations: scene after scene of erotic opportunity in which he remains a spectator. By the end, an old friend of Bill’s has disappeared, a woman linked to Ziegler has mysteriously died, and Bill has discovered a secret society of unsuspected reach and cruelty. All this Ziegler explains away in his concluding speech as if he were a therapist. But the explanation proves too much: the romance of the night has so thoroughly enveloped us that no realistic antidote can dispel the illusion. Kubrick knew what he was doing when he instructed Pollack to deliver the plot-resolving speech in an operatic manner that defies credulity. Rational explanation will never outweigh mystique. There are conspiracy theories but there is also conspiracy fact.

Eyes Wide Shut was a project Kubrick had nursed for a long time: it came out in 1999, twelve years after Full Metal Jacket. He was held back partly by a superstitious fear that this story of infidelity could jinx his marriage. It is his most human film; and it was created with his usual exorbitance (fifteen months of filming, exceeding the record held by Lawrence of Arabia). The opening scenes give the motive for the complex plot: husband and wife will be tested by their parallel dreams of infidelity. They are both tempted at the party: he by two models who offer to escort him to a private room, she by an exceedingly handsome old-world aesthete, who praises her beauty and says that he must see her again. Alice says no, and when he asks why, she returns a flirtatious smile and shows him her wedding ring. Cut to Chris Isaak’s ‘Baby Did a Bad Bad Thing’; Bill and Alice are naked in the mirror, thinking of the almost partners they left at the party, even as they now make love to each other. By the final scene, they will be buying toys for their daughter at FAO Schwarz; it is time to go on with their lives, and the last word of Kubrick’s last film is the dirtiest word in the language. It is what they have to do, an imperative of loyalty.

One unshakeable impression has stayed with me as I looked back at Kubrick’s movies a second or a third time. He always means it. The focus never really pulls away; there is a substance, a purpose, a weightiness in the delivery; the film says what it says without the seduction of theatricality. This is a surprisingly rare feeling to have regarding even a very gifted artist. If Kubrick sometimes treated existence itself as a problem to be solved, integrity seems the right word for his willingness to be embarrassed by the result. He put himself into his work. Still, why drive the preoccupation with detail to such an obsessive limit? Why the insistence on working at home? Why the control of every monetary matter, from the key grip’s salary to the per-hour rate for extras? Kubrick once offered an explanation by analogy. Usually, the daily work on a film is done by the editor ‘as they go along’, with the director somewhere in the background, and ‘when the film is done, they look at the film and dictate some notes about it, and the film editor tries to do what they say, and then maybe they look at it again and they do it again.’ But that, Kubrick objects, is ‘like trying to, say, redesign a city by driving through it in a car. You can notice a few things and say, “Put that traffic light in the middle of the street” or “Those buildings over there look kind of shabby” or something, but if you really want to do it right, you must do it yourself.’ He planned the shots so that he knew what was in them from corner to corner; and he was present for every minute of the editing. If this sounds like a commitment that excluded any real partnership, that was indeed the case. Between projects, Kubrick would press his friends or relevant associates for information, in phone calls that might last four or five hours, or seven or eight.

The tightening of his inward compulsions and inhibitions kept pace with the growth of his deserved fame. He directed seven films in his first decade, only six in the following 35 years. Four rank among the great films of the last century: Paths of Glory, Lolita, Dr Strangelove and Eyes Wide Shut; one other, The Killing, is a masterpiece in a minor genre. Meanwhile, 2001 stands as the cinematic equivalent of a hapax legomenon, a visionary thought experiment that had no precedent and will have no successor. Full Metal Jacket is the only existing attempt to portray the instincts that lead to war without a trace of either pity or vainglory. Kubrick greatly admired Kieślowski’s ten-part Dekalog, and said, in a preface he wrote for its screenplays: ‘they have the very rare ability to dramatise their ideas rather than just talking about them’; also, ‘they do this with such dazzling skill, you never see the ideas coming.’ The encomium makes a fair description of what seems most unusual in his own work.

The happiness of his private life, as Kolker and Abrams make clear, seems to have been a cause of the slow accretion of his body of work in his middle years. He doted on his three daughters, Katharina, Anya and Vivian, and never stopped adding to his collection of cameras and computers, dogs and cats. With every human competitor, however, he had to have the edge, and he kept them in line by beating them at chess. He welcomed the chance to interrupt filming by making large insurance claims for accidents on the set: the interval allowed him to consider the innumerable revisions he might still make. Shortly before his death, he delighted himself by winning a defamation suit against Punch. True, it was a humorous magazine, but it had called him insane and he was following a usual pattern, joking about the solemnity and being solemn about the joke. Once, on the set of Full Metal Jacket, when he had spent a long time double-checking a camera, one of the extras muttered: ‘Get off the crane.’ Kubrick paid no attention and went on checking until a second extra pitched in, ‘Get off the fucking crane,’ at which he looked up and demanded: ‘Who fucking talked?’ One of the men said, ‘I am Spartacus,’ another fell in, ‘I am Spartacus,’ and so it went, an act of organised resistance, a homage and parody of a moment he had shot from a different crane. Stanley Kubrick of the Bronx, filming in the demolished Beckton Gasworks which doubled as the bombed-out city of Hue, gave up the pretence of discipline for a moment, laughed and went on with his work.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.