Tim Clayton’s book is a magisterial study of a great popular artist: a full-scale interpretation of James Gillray’s output of satirical prints, and a biography that warrants comparison with the best ever done on an 18th-century artist. It has been furnished with gorgeous reproductions, along with close-ups that illuminate Gillray’s care for visual detail and his uninhibited verbal wit. This account removes once and for all the question of why Gillray should have poured his enormous talent into a ‘minor art’. Henry Fielding’s Shamela – just a smack at Pamela – was largely confined to mockery of its deadpan original, but his Tragedy of Tragedies; or, the Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great was attuned to a broader climate of false feeling and the bombast that floated it. Gillray worked from a similar ambition. Unlike Fielding, he made a career of it.

His nearest precursor was Hogarth, in the kinetic scenes of Marriage à la Mode, A Rake’s Progress and, most of all, the series titled Humours of an Election. That production dates from 1755, the year before Gillray was born. His father, a blacksmith by trade, had served in the army for a decade and lost his right arm in 1745 in a battle against the French at Fontenoy. Reference to this mutilation, a perpetual reminder of the horrors of war, would show up sometimes overtly but also by displacement in Gillray’s prints. Both parents were faithful members of the Moravian Brotherhood – a key, perhaps, to Gillray’s surprising conversancy with biblical texts. He studied at the Royal Academy, only a few years after its founding in 1768; and it was there that he may have met Thomas Rowlandson, the other outstanding caricaturist of his generation.

Alice Loxton spins her exuberant popular history around that friendship, and calls on their mutual friend Henry Angelo for testimony on Gillray’s early mastery: ‘The facility with which [he] composed his subjects, and the rapidity with which he etched them, astonished those who were eye-witnesses of his powers. This faculty was early developed – he seemed to perform all his operations without an effort.’ One of the first prints to reveal something of his political animus was Six-Pence a Day, a poster-like appeal against recruitment for the American war in 1775. The work that followed would be notable for its candid presumption that public figures are fallibly human, therefore corruptible, and no single glimpse is likely to tell the whole story. Hence Gillray’s serial return to certain characters – Charles Fox, Napoleon, George III, the Prince of Wales, Burke, Sheridan and Pitt. The motive, the posture, the degree of deplorable wheedling would shift even as the character stayed the same.

An earlier biographer, Draper Hill, judged that Gillray had ‘lifted his calling from a trade into an art’. How did he do it? And why did the revival of the comedy of humours which lasted from Tom Jones to Thackeray’s Book of Snobs, and in which Gillray now seems a central force, shut down in the mid-Victorian years almost as unaccountably as it began? In his essay ‘On Modern Comedy’, Hazlitt offered a provisional explanation: comedy, he suspected, naturally arises from ‘a certain stage of society’ in which

men may be said to vegetate like trees, and to become rooted in the soil in which they grow. They have no idea of anything beyond themselves and their immediate sphere of action; they are, as it were, circumscribed, and defined by their particular circumstances; they are what their situation makes them, and nothing more.

This ‘circumscribed’ character made for an eccentricity that brought public persons and social types under the sharp eye of caricature. But there is a levelling tendency in modern manners, Hazlitt added, by which ‘we are drilled into a sort of stupid decorum, and forced to wear the same dull uniform of outward appearance.’ In 1813, when his article appeared, it already seemed that the satire of manners so dear to caricature was dying out. People were becoming too like one another, or at any rate too conscious of the ways that they had better not seem unlike. There was something bold, scapegrace or oblivious about a ‘character’ who was also a type. Something was lost with the protective modesty and self-surveillance that came with the spread of a standard of politeness.

Gillray’s annus mirabilis was 1782, when he produced 52 plates, most of them on political subjects. The great events he would trace in the next quarter-century include the rise and rapid fall of the Fox-North coalition; the 1784 election, which ushered in the long reign of Pitt the Younger; the madness of George III and the consequent Regency Crisis; the premonition of war and the actual wars with revolutionary France and then with Napoleon. But when you read about his career step by step you realise how little his perspective ever widened to become international in scope. At the end of a century in which Britain fought seven wars with France, he was interested almost exclusively in the way French tendencies might look inside England.

Gillray clearly found everything he learned about the revolution repellent. But his satire was unsparing towards the holy fears and anti-revolutionary propaganda that kept war fever dependably high. The larger the scale of revolutionary outrages, the surer the excuse for slaughter. Pitt, in the crisis that never subsided for long in all his years as prime minister, threaded his way among the moods and exigencies of the moment. He would hold back a proposed military commitment until the opening appeared wide enough; he rode the storm prudently, efficiently, with a cold Machiavellian reserve. And it is the deftly domineering Pitt in all his guises and functions who becomes the all-engrossing subject of Gillray’s commentary over the next three decades.

One of his best-known caricatures shows Pitt and Napoleon seated at a dining table too small for both; between them stands a spherical pudding that is also a globe. The wartime leaders are carving up the world, and they intend to eat it. Pitt has already mastered the etiquette: seated in his chair, erect with entitlement, he is an image of Ability Incarnate, calm and complacent, without a shred of superfluous curiosity about the edible thing that will soon be on his plate. Even from a low posture he manages the condescension of slicing down. But Napoleon is ravenous – will there be enough for him? Gillray called this unsentimental set piece The Plumb-pudding in danger; – or – State Epicures taking un Petit Souper. A little snack, you understand, and not the real meal. They may have other worlds to swallow later on.

Poor Napoleon! Confronted by the plum pudding, he has to stand on tiptoe to carve at all. This caricature was a slander on his stature, as Loxton points out: he was actually five foot six, average for a man of that time. But the image of Little Napoleon would be stamped on the public mind; even his indisputable successes could be mocked as evidence of a mismatch of aspiration and endowment. (‘A fiery soul,’ as Dryden said of another usurper, the Earl of Shaftesbury, ‘which, working out its way,/Fretted the pygmy body to decay’.) For this misrepresentation, Gillray deserves a large share of the blame.

The Plumb-pudding in danger was published in February 1805, a few weeks after Napoleon saw himself crowned emperor in a ceremony attended by the pope. Gillray’s straight anti-Napoleon pieces, such as Maniac-Ravings and The Corsican Pest, operate at a considerably lower level. Gross conceptions finely executed, they perform their cheap trick with unmistakable gusto: Napoleon stamping the ground in a rage like Rumpelstiltskin (his angry jig has punctured another globe with a hole in the vicinity of Cape Horn); or again, Napoleon the ‘pest’, impaled on a long fork and shoved into everlasting flames by Beelzebub. The grotesque energy of Maniac-Ravings was suited to its critical moment, 24 May 1803, a few days after the renewal of war with France. The Corsican Pest, from October of that year, would have done nicely as a placard to stir the blood of the 350,000 men who answered the government’s call for volunteers. These over-the-top cartoons raise a question that recurred throughout Gillray’s career. Did his hyperbole ridicule the cause it was supposed to serve? And if it did, then whose side was he on?

Gillray’s arrest for blasphemy, in January 1796, came in response to a caricature, The Presentation – or – The Wise Men’s Offering, which showed a pious Charles Fox and Sheridan, along with the generic London bawd Mother Windsor, presenting the baby Princess Charlotte to a drunk Prince of Wales. Published soon after the treason trials of 1794 and the gagging acts of 1795, The Presentation was innocuous by Gillray’s standards. His offence lay in the turn given by the title: if the bowing and scraping Whigs are the wise men of the East turning up for the birth of Christ, then the Prince of Wales is the Virgin Mary and the baby is no more his child than Jesus (strictly speaking) was hers.

Such complications of image by word are a constant feature of Gillray’s art. He loads down his political personalities with visual and verbal reminders of their past scandals, compromises and failures, public entanglements and vanities. The fashion for caricatures widened the commercial prospects not only for Gillray but also for Rowlandson, James Sayers, Henry Bunbury, Isaac and later George Cruikshank, and encouraged the luminaries of the hour to want to see their own faces in the shops that sold the prints. To be caricatured was proof of ‘true fame’, but a peculiar understanding was involved: few of those who weathered the ritual came out more honourable than they had appeared when they went in. Many were diminished permanently by the exposure – never again would they be entitled to implicit trust.

One of the many politicians who sought validation through caricature was George Canning, a young gun of the Foxite Whigs who turned in 1792 to side with the Pitt ministry. Canning went out of his way to solicit recognition by Gillray in particular, advising a mutual friend, James Sneyd, to offer Gillray the use of his franking privilege for a heavy sheaf of ‘prints or drawings to transmit to Mr G. or he to you’: Sneyd should send Gillray to Canning’s door, which he would answer, to perform the service and to get his face looked at. A bribe of a conventional sort, maybe, but it could also have been a political trap. As Clayton puts it, ‘the coincidence of Canning’s invitation conveyed by Sneyd to Gillray on 21 January 1796 with Gillray’s arrest on 23 January looks suspiciously neat.’ Portray me, Canning may have been saying, and I who can frank your heavy-duty packages will arrange for your bail and have the charge lifted.

If that was the bargain, Gillray repaid the debt with characteristic wit and economy. He made Canning wait nine months before casting him in Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion – an apocalyptic cartoon in which Pitt (manacled to a maypole whose Jacobin cap says ‘Libertas’) is subjected to a flailing by Charles Fox, while lesser opposition members, on the balcony of Brooks’s club, hold up a ‘New Code of Laws’ over a tray of severed heads with the caption ‘Killed off for the Public Good’. Meanwhile, across the street, outside the Tory White’s club, two gentlemen have been hanged from a lamp-post by the English armée du people, and one of them is Canning. His face is very small.

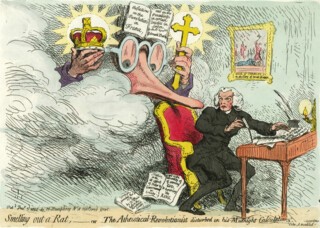

Only Gillray could have rendered the anti-revolutionary mood with such comprehensive hysterics – the whole crowd of figures suspended between fear and fervour, with something weirdly jolly in the mixture. Where will this go next, it seems to ask. At the opposite extreme of his revolution satires is the cartoon showing just two sombre figures, Edmund Burke and the Reverend Dr Richard Price. It was Price’s republican sermon ‘On the Love of Our Country’ that had given Burke the pretext for his Reflections on the Revolution in France. Gillray entitled his double portrait Smelling out a Rat; – or – the Atheistical-Revolutionist disturbed in his midnight ‘Calculations’. Intruding from the left, Burke is a ghastly, glowering face out of a cloud, his beak of a nose surmounted by gigantic spectacles; in his left hand, he wields a dazzling crucifix, and in his right, a crown. As for Price, startled at his compositional labours, he has dropped his pen and now recoils in mingled horror and resentment. Burke, no doubt, is the state detective and protagonist here, Price the guilty rat, yet one is apt to feel divided sympathies. Gillray, for all his resistance to revolutionary enthusiasm (indeed his distrust of all enthusiasm), was utterly repelled by any claim to the office of state censor.

He caught Burke serving that function in The Chancellor of the Inquisition marking the Incorrigibles, published in March 1793: a portrait of Burke, the turncoat from the opposition, now in the monkish garb of a Spanish inquisitor or lord chancellor, severe and upright as he sets down names on a ‘Black List’ which contains captions such as ‘The Man of the People has lived too long for us!’ Clayton uncovers the motive with admirable lucidity: ‘Freedom of speech was a professional necessity for Gillray and he was always robust in its defence, and suspicious of any form of restraint’; he also ‘deeply disliked’, and ascribed in part to the influence of Burke, ‘the use of spies and informers’ by John Reeves and the Association for Preserving Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers. A mostly sceptical reader of Burke’s anti-revolutionary writings of the mid-1790s, Gillray cared enough for his Letter to a Noble Lord to pay it the homage of a whole-length travesty, Pity the Sorrows of a Poor old Man (February 1796). The passage from the Letter that he invoked there against Burke, he would repurpose a decade later to undermine Burke’s accuser, the Duke of Bedford. His versatility was always adventurous and unshameable.

Gillray’s favourite face was unquestionably that of Charles Fox – always pictured as vaguely dissolute, with a five-day beard, as careless of his posture as of his associates. Gillray would throw in Fox anywhere and everywhere. Fox was loved even by his enemies, and it was a glad day for Hannah Humphrey, Gillray’s printseller and eventually his life partner, whenever Fox came into the shop to buy a caricature of himself. ‘Ah Betty,’ Clayton reports her sighing to her assistant, ‘there goes the pattern for all gentlemen!’

Gillray’s deployment of George III was more variable. He is frequently summoned as a kind of national mascot, a dependable bystander to the doings of the commonwealth, but Temperance enjoying a Frugal Meal ridicules George III and Queen Charlotte for their pretensions to thrift. The royal couple are dining at a table lit by one candle, drinking water and not wine, and on the wall a picture of a biblical scene: manna falling from heaven. The strongroom door, however, is double-bolted for reasons that may be the reverse of frugal. Apart from his status as a miser and exemplar of domesticity, George III appears in other prints as a farmer, an estate caretaker, a rider gratis in a well-appointed coach. At a certain point Gillray starts to identify the king with John Bull – a freeholder of uncertain description, rough without meanness, and if mentally thick, nonetheless a durable and somehow a reassuring presence.

William Blake’s parents, like Gillray’s, belonged to the Moravian Church, and their early careers ran parallel in other ways. Blake’s first book, Poetical Sketches, came out in 1783, the same year as Gillray’s first major political cartoon, Neither War nor Peace, a satire on the Fox-North coalition. Whether in painting or poetry, Blake never dealt minutely with the surface of politics, as Gillray lived by doing, but they shared a boundless curiosity regarding the true and false prophets of a time of revolutionary upheaval. Blake stared into the abyss of contemporary society, as from a height, but he could meet the ground with surprising literalness – when for example he inserted the names of contemporaries in poems such as America: a Prophecy, or when he responded to Burke’s memory of the queen of France (‘surely never lighted on this orb, which she hardly seemed to touch, a more delightful vision’) with a blistering couplet: ‘The Queen of France just touched this Globe/And the Pestilence darted from her robe.’ If Blake’s method was occasionally to discover living correspondences for his ‘visionary forms dramatic’, Gillray always worked from the bottom up. Faced with a lunatic spellbinder like Richard Brothers, he would include him, together with Famine and Death, in Presages of the Millennium – a cartoon published on 4 June 1795, the king’s birthday and also the day marked by Brothers for the earthquake that would destroy London.

Presages of the Millennium shows Pitt astride the pale horse from Revelation: ‘And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him.’ He has become Death itself and, in the famine year 1795, he rides roughshod over the ‘swinish multitude’, leaving in his track the members of the opposition, cringing and mangled under the horse’s hooves. Further back in this retinue are his ferocious assistants, demon or dragon shapes in the sky, a raging lion and soldiers variously armed with bow and arrow, spear, sword and scythe. It is a studied piece of Rubenesque muscular motion, comical-grotesque but frightening all the same. Hunched and leaning far forward, Pitt on the horse is pale too. Gaunt, starved and hollow, he is the victim as well as the executor of the death he represents. And yet he makes a prodigious figure, far more dreadful than the swarthy and golden-crowned king of the shades who seems to have dropped down from the clouds in Benjamin West’s Death on the Pale Horse, which Gillray could have seen at the Royal Academy.

Pitt, in this unforgettable image, seems driven forward by a resistless wind. He no more ‘controls events’ than any politician in time of war. Presages of the Millennium is a mad allegory, impulsive, opportunistic and utterly free. You would no more seek to resemble this protagonist than the vegetal parasite (also Pitt) whose roots in Toadstool upon a Dunghill have sunk so deep in the king’s substance as to be indistinguishable from the Crown itself. Far from the barely human carcass of Presages, the prime minister in Toadstool, published just four years earlier, was bloated, with swollen cheeks and a double chin. Only on a third or fourth look does the scarlet thing under the dunghill reveal itself as the Crown. Pitt seems entirely the creature of the king, but he is sucking the life out of his host. His toadstool roots look like the tentacles of an octopus.

Occasionally Gillray salted his usual diet of political comment with a full-scale parody of the academic milieu in which he was trained. A prime invitation to contempt was the opening of the Shakespeare Gallery by the London alderman John Boydell. There was a spiteful motive, since Boydell had rejected Gillray’s offer to engrave one of James Northcote’s paintings for the gallery. Gillray went to the opening anyway and made notes and sketches on some cards he had brought along. His unwelcome visit became an occasion for the anti-institutional romp Shakespeare Sacrificed; – or – The Offering to Avarice. Gillray’s visual commentary took in, among others, West’s Fool from King Lear, Fuseli’s Bottom and John Opie’s Perdita. The cram of mock-laudations has the effect of reducing the stature of every painter who strove to exalt himself by association with Shakespeare. The claim to distinction by any of the crowd is sunk and scrambled by their numbers and their confusion. In Media Critique in the Age of Gillray, Joseph Monteyne suggests that the spirit of ‘iconoclastic destruction’ in Gillray’s art-historical mock epics ended by ‘dramatically revealing Gillray’s own creative satirical dynamism’. That seems an apt characterisation of his art more generally, and it brings out Gillray’s affinity with the author of The Dunciad.

On a smaller scale, he could always do one-off travesties – things like his send-up of Reynolds’s Lady Sarah Bunbury Sacrificing to the Graces. Gillray’s parody was called La Belle Assemblée. In place of the gracious solitary aristocrat, multiple ladies are muscling into line for the sacrifice; among them, as Loxton puts it, ‘the rotund, overstuffed Mrs Albinia Hobart’ and ‘Lady Sarah Archer, famed for her riding skills and, according to Gillray, always with whip in hand’. Gillray had a pronounced disdain for the newborn institutions of cultural legitimacy. His temper here was the reverse of sincere aspirants such as Benjamin Haydon and James Barry, and he scored a second hit with Titianus Redivivus; – or – the Seven-Wise-Men Consulting the New Venetian Oracle. His target had delivered itself ready-made. Ann Jemima Provis and her father, Thomas, had hoodwinked West and seven other academicians to purchase (at ten guineas each) the ‘secret’ of Titian and his classic Venetian colouring. Gillray lined up the gullibles, seated and well-behaved like spaniels awaiting their biscuits, each with his easel ready and palette filled, and each emitting a thought balloon with a distinctive motto: ‘Will this Secret make me Paint like Claude?/Will it make a Dunce a Colourist at once?’ Or ‘As I in Reynolds style my works Begin/Wont Titians Finish hoist on me the Grin?’ The words ‘hoist’ and ‘grin’, taken together, are a fair clue to Gillray’s own secret.

The truth of art, as Gillray saw it, derived neither from the colour mastery of the Rubénistes nor the line mastery of the Poussinistes – a French academic quarrel of a century earlier which Reynolds had carried forward in his Discourses on Art. The truth that mattered to Gillray owed much more to the intuitions of physiognomy. Johann Kaspar Lavater’s Physiognomic Fragments stirred considerable interest when they were published in the late 1770s. ‘What,’ Lavater asked, ‘could less resemble the image of a living man than a shadow? Yet how full of speech!’ Monteyne devotes some provocative pages to Gillray’s experiments with the physiognomic genre of doublûres – sketches of a portrait-face uneasily shadowed by its lurking counterfeit. This thought seems to underlie Gillray’s dark-side-of-the-moon portraits in Doublûres; – or – striking Resemblances in Physiognomy. Diana Donald made the necessary inference in The Age of Caricature (1996): ‘If heart and face were essentially connected, it followed that … those who looked alike must share the same character.’ So with Fox, Sheridan and the other double portraits in Doublûres: ‘Fox’s bottle nose has a physiognomic sympathy with the “fiendish” black spreading jowl’; the same goes for ‘the blubber lips’ of Sheridan, when ‘the lower part of the face gains the ascendant.’ Expression, of course, will change in a human face, depending on the stimulus of the moment and the emotion, but physiognomy tells you the limit. We now take constancy of expression as a ‘given’ of caricature, but nothing made it inevitable except a conviction regarding that limit. The viewer’s recognition must be instant – hence the necessity of an almost unvaried expression to identify each political character.

Politics requires the maintenance of a façade that hides the self and may in the end obliterate it – if there was ever another person beneath. The doublûre points this moral by shadowing the known visage with a background ghost who thinks words that will come out muffled when spoken. But what is true of politics is true of the masquerade of society more generally, and here again one is reminded of Blake: ‘Her whole life is an epigram: smack smooth, and neatly penned,/Platted quite neat to catch applause, with a sliding noose at the end.’ Society itself is a satirist and a thief; what it steals is the person you are.

Gillray’s mischief was of an unusual sort, at once refined and coarse, and sometimes with an opacity hard to penetrate even after several looks. Most people who have cared for his work, and some who knew him well, confessed the difficulty of weighing the exact meaning of the ridicule. In a letter to the Athenaeum in 1831, Edwin Landseer recalled an apparent joke in a meeting to support (in Clayton’s words) ‘a society for the relief of decayed artists’. Plenty of wine had been drunk with dinner when the artists were asked ‘each to propose a toast to a public figure; when it came to Gillray’s turn he made them all kneel reverentially and drink to Jacques-Louis David, a notorious republican, as the “first painter and patriot in Europe”.’ The anecdote is second-hand but entirely credible, and the question only occurs later: could he have meant it? No one was sure at the time. Draper Hill surmised that the meeting in question must have taken place between 1792 and 1794, in which case Gillray could have been evoking David’s impeccably republican and ascetic Oath of the Horatii rather than, say, Napoleon Crossing the Alps. But even a clear assurance on such details – given Gillray – would not resolve the question. He was capable of using the word ‘great’, as Fielding did in Jonathan Wild, to encompass the great-vulgar and the small and criminal. Satire is not one of the liberal arts, but it may be the only art that is liberating by its nature. It is not therefore virtuous: it frees the artist from restraint, in a way that may do harm as well as good.

What do we mean by mischief? It throws a wrench in the works. Whether in a small group or in society at large, it starts with a joke or a puzzle and may end by stirring up strife among friends. This non-moral regard for effects is combined with pleasure at being the indifferent cause of those effects. It is the quality of the mischief-maker to walk away and do the next thing. Flat observation, during or after the mischief, makes a satirist. But in its pure state (Juvenal and Swift, not Horace or Pope), the satirist does not pretend to sympathise or to administer a cure: people are what they are; no point reading them the Riot Act. Watch the riot from a safe distance, and wonder at the animals who would do such things.

What was the expression on Gillray’s face when he drew the solo portrait of Pitt entitled Uncorking Old-Sherry? Seen full-figure in profile, Pitt uncorks the bottle to release a cloud of froth containing ‘Damn’d Fibs’, ‘Old Puns’, ‘Stolen Jests’ and so on; the caption gives some words (roughly reconstructed) that Pitt spoke in answering a routine denunciation by Sheridan. Is this a relaxed grin at Sheridan’s expense? If so, the joke plays rather narrowly but the words quote Pitt in a moment of undoubted suavity and command. ‘The honourable Gentleman,’ Pitt in Gillray’s version says,

tho he does not very often address the House, yet when he does, he always thinks proper to pay off all arrears, & like a Bottle just uncorkd bursts all at once into an explosion of Froth & Air; – then, whatever might for a length of time lie lurking & corked up in his mind, whatever he thinks of himself or hears in conversation, whatever he takes many days or weeks to sleep upon, the whole common-place book of the interval is sure to burst out at once, stored with studied-Jokes, Sarcasms, arguments, invectives, & every thing else which his mind or memory are capable of embracing whether they have any relation or not to the Subject under discussion.

The riposte in the House of Commons was delivered in Pitt’s speech on the Defence Bill of 6 March 1805; the caricature went on sale on 10 March, and Gillray’s transcript was said to have been more accurate than the newspaper reports.

But then one remembers: this is Gillray looking at Pitt. Are the redundant words a two-edged sword? The old sherry in question could surely be Pitt’s as much as Sheridan’s – Pitt, whose very heavy drinking, which now and then visibly impaired his performance, was a matter of general knowledge in the House; whether he could turn a dexterous response to a query on the Treasury budget was less in question than whether he would be steady on his feet. This matters all the more when a well-rehearsed efficiency is your main strength. ‘Mr Pitt proceeds,’ Coleridge wrote in 1800,

in an endless repetition of the same general phrases. This is his element: deprive him of general and abstract phrases, and you reduce him to silence. But you cannot deprive him of them. Press him to specify an individual fact of advantage to be derived from a war, and he answers, Security. Call upon him to particularise a crime, and he exclaims, Jacobinism. Abstractions defined by abstractions – generalities defined by generalities!

Did Pitt’s variations on a few standard topics charm the ear of Gillray more than the twice-told paradoxes of Sheridan? The cartoon certainly displays an irrepressible fondness for the Pitt who uncorks the bottle. And the score goes to him in the end, a point attested by the gloomy heads of Sheridan, Fox and the rest in their separate bottles on the opposition bench; as well as the cloud of froth that spells out the word Egotism. Yet this is the same artist who conceived Presages of the Millennium and Toadstool upon a Dunghill.

Give him the slightest pretext, and Gillray will take an off-centre observation, as basic as a pun, and penetrate all its absurdity. The ‘broad-bottom ministry’ was the popular name given to the Ministry of All the Talents of 1806 – another coalition government including Fox, this time headed by William Grenville – which foundered on the issue of Catholic Emancipation. There are, Gillray suggests in Making-Decent – i.e. – Broad-bottomites getting into the Grand Costume, not enough mismatched clothes to cover all the bottoms. A year later he commemorated the ministry’s fall with A Kick at the Broad-Bottoms! – i.e. – Emancipation of ‘All the Talents’. George III has stepped angrily off his throne, and his mace is about to descend on Grenville’s back as he explodes: ‘what! – what! – bring in the Papists? – O you cunning Jesuits you!’ A month after that, Gillray’s refusal to mourn the departed talents was translated outdoors in The Pigs Possessed; – or – the Broad-bottom’d Litter running headlong into the Sea of Perdition, where George III, something between Jesus and John Bull, chases the broad-bottom Gadarene swine over a cliff.

In the field of art history, ‘media’ has become a word to conjure with, a cover term for every kind of visual production. This makes differentiation by genre as otiose as the attempt to distinguish between scraps and prints or between scratches and lines deliberately etched with acid. Monteyne, in his ingenious study, is looking to establish affinities between the Gillray-Rowlandson milieu and the Parisian literary underground made familiar in the scholarly work of Robert Darnton. At a longer distance, the aim is to declare Gillray the blood brother of ‘tinkers, tailors, blacksmiths, cobblers’. The scratched and stippled surface of an abandoned Gillray sketch is said to show his ‘unusual attempt to increase the significance of his work by seeming to destroy it’, so what looks like a disgusted scribble may be not a throwaway but an effort ‘to indulge in non-communication, and test the limits of representation’.

The same argument might be extended to stipple-engraving generally – but to what end? No matter how severe the impediment, we read the image as if it wanted to represent or imagine something. Abstraction, expression, ‘significant form’, whatever the criterion ends up being, the work will be read as if it communicated the sense of a thought, an action, a person, a mood. The social-deconstructionist view does (fairly enough) push into focus Gillray’s attitude of almost continuous negation. What it forgets is that he held the reins and supplied the goods for a commercial enterprise, and he never worked more than a stone’s throw from the academic painters whose diversions and follies he tracked with clinical irony. At his greatest, he earns the kind of praise Charles Lamb awarded to Hogarth’s Gin Lane. Not only the main figures, Lamb wrote, but ‘every thing else in the print contributes to bewilder and stupefy, – the very houses … tumbling all about in various directions, seem drunk, – seem absolutely reeling from the effect of that spirit of diabolical frenzy which goes forth over the whole composition.’ The same infectious, oppressive crowding of a feeling into every corner and crevice, Gillray aimed at and achieved in a print such as Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion.

From his earliest efforts, he gained a following not only among the new reading public who got their politics from newspapers, but also from a more purposeful mixed audience of aesthetes and connoisseurs. Among them were critics for the German journal London und Paris who admired ‘his extensive literary knowledge of every kind’ and his unique ‘ability to capture the features of any man’. With such scholastic equipment, a cartoon as blunt as Confederated-Coalition; – or – The Giants storming Heaven, on the failed opposition attempt to dislodge Pitt and Lord Melville in 1804, could be appreciated in warm exegetical detail for its allusion to Virgil’s Georgics and the giants heaping Pelion on Ossa in their assault on Mount Olympus. There was no question of putting in references for the Germans. The Greek myths were as essential as John Bull to the constitution of Gillray.

He had come of age during the ascendancy of Gainsborough, Reynolds, Wilson, Romney, John Hamilton Mortimer and Joseph Wright of Derby, but by luck and much more by craft, he found an opening elsewhere. The previous undignified status of caricature bore no relation to the gifts of those who pursued it, and Gillray was as plainly the superior in genius to Benjamin West, George Morland and Benjamin Haydon as Dickens and George Eliot were superior in ambition to Tennyson and Matthew Arnold. In the case of caricature as well as fiction, the artist in the newer genre was doing something that the well-precedented talent in the dignified genre could never have conceived of. (Arnold’s put-down of modern fiction as ‘domestic epic’ registers a typical uneasiness at such shifting hierarchies.) For reasons hard to assign with any precision, the humbler art may become the more interesting field for original talent. Hazlitt reports his friend James Northcote (the biographer of Reynolds) saying in conversation that Reynolds himself ‘did a number of caricatures of different persons, and could have got any price for them’, but it would not square with his pretensions: ‘Sir Joshua would almost as soon have forged as he would have set his name to a caricature.’ Yet Northcote himself singled out for praise Gillray’s Revolutionists’ Jolly-boat, in which the opposition leaders Fox and Sheridan, escaping from their party’s wreck, exhibit a demeanour even Dante could not have rendered ‘more sullen and gloomy’.

It may be wisest to think of caricature as a necessary recoil of society against its own coercive artifice – a partial antidote to some of the abuses of the modern state just as that state was hardening. ‘Th’oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely’ never get the lashing they deserve; Hamlet was in a Gillray mood when he told Rosencrantz and Guildenstern ‘Man delights not me; no, nor woman neither, though by your smiling you seem to say so.’ One has no doubt, after Clayton’s conscientious narrative and analysis, that Gillray leaned towards frankness in all public dealings. Even so, it is painful to read the abject letter he sent to the young reptile Canning and his agent Sneyd when compelled (from a sudden fear of libel) to destroy the plates for the commissioned illustrations he had made from texts in the Anti-Jacobin. The letter is confused and pitiable; a warning that the only honest politics may be anti-politics – not just to play both sides, as Gillray did, but to stay free of party altogether. He seems to have reduced this maxim to an uneasy practice even when he was hired by one side. Caricature is the doublûre of politics.

His last years, with progressive blindness encroaching, witnessed a terrible emotional decline. The flailing or abrupt movements he liked to hit off almost anywhere, of persons hurling themselves into a flight of desperate action – Pitt at the millennium, or Napoleon in The Spanish Bull-Fight, tossed from the horns of a rampant bull – lend plausibility to the report of an attempted suicide when his eyes and hand were no longer of use. His powers began to fade in 1807, and he suffered from episodic and then protracted melancholia. He once addressed his disciple George Cruikshank, ‘You are not Cruikshank, but Addison; my name is not Gillray but Rubens,’ all the while, Cruikshank said, moving his hand in the air ‘as if in the act of painting’. An enigmatic character who kept to himself but loved to complicate and provoke, Gillray showed his freedom in his art. He owed what happiness he enjoyed to his partnership with Hannah Humphrey, but outside of their business dealings little is known about the nature of the collaboration, except that it endured without a rift. There is a story of the couple starting out for church and Gillray stopping: what could they get from marriage that they did not have already? He used Samuel Fores and other sellers, too, but began giving Humphrey his work early on, in 1787, and dealt with her exclusively from 1791. Together they outbraved his run-in with the censorship police during the treason-panic years 1794 and 1795, but otherwise led a mostly uneventful life in a quarter full of writers and artists, in St James’s Street. Nearby were the rival booksellers Debrett’s and Hatchard’s, which served the Portland Whigs and Pittite Tories respectively. Gillray had an unrestricted and daily view of his quarries.

A critic in the Examiner in 1824, reviewing a cheap compendium of his prints, answered the Tory digs in the text with a reminder: such ‘trite vituperations’ came ‘with special ill grace in a commentary on an artist who was known to be a democrat in his heart’. But let us not be sentimental. Gillray was no more fundamentally a democrat than he was a monarchist. He was that rare and precious thing, an anarchist without a hunger for disorder. He died on 1 June 1815 – two weeks before Napoleon lunged for a final slice of the pudding. Tim Clayton has shown in detail how he came to deserve the settled eminence no one would now deny him, but part of the reason is a trait only distantly connected with talent. ‘Gillray,’ Clayton says, ‘was never entirely biddable.’ Nor was he snug with the great and guarded whose lives are a long succession of bids. His will left everything to Hannah Humphrey.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.