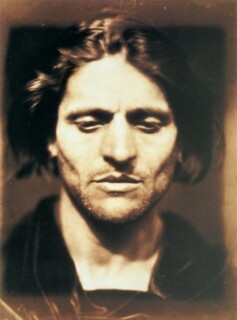

He is not one of her Great Men. After all, he has no beard. Yet the 1867 portrait that Julia Margaret Cameron called ‘Iago’ is her most startling photograph. The face, captured so close up as to suggest a 21st-century candour, has the long features and brooding gaze of Frank Finlay, who played the villain to Laurence Olivier’s grimacing Moor. Nevertheless, the title is mysterious: this is not one of Cameron’s fancy-dress characters; no strawberry-patterned handkerchief identifies him. It is as if she saw something essential in his face – that to be duplicitous you should look alluring? That with such sculpted cheekbones the idea of being two-faced takes on new meaning, one face seeming to float on top of another? The sitter isn’t named, and the picture is simply described as a ‘study from an Italian’, as though the ‘I’ in Iago were a misprint for a ‘d’.

Cameron created a pantheon of hairy brainboxes, boasting that ‘the greatest men of the age … say I have immortalised them.’ The adored face of Henry Taylor – whether photographed as himself, or as King Ahasuerus or Prospero – rests on his luxuriant beard like an afterthought; Joseph Hooker, one of her most keenly defined portraits, looks as if he is trying to escape his whiskers. The great ones grumbled they weren’t pretty enough. Tennyson, whose facial hair adds much to the dishevelment of the picture he called ‘the dirty monk’, said she had given him bags under his eyes. Carlyle complained that he looked ‘ugly and woebegone’, but his apparent anguish gives him a transfixing vitality. He seems to be shuddering into life.

Without the aureole of greatness, and with no recorded complaints, Cameron’s female sitters – heads tilted, eyes cast down, in semi-profile – often seem to be melting away, into melancholy or into someone else: ‘The Lily Maid of Astolat’, Alethea, ‘Il Penseroso’. But not always: Mary Hillier, who served at Dimbola, Cameron’s house on the Isle of Wight, is magnificently bold as Sappho. ‘Pomona’ looks grumpy. And half-light can enhance an ambiguous challenge: it is hard to know whether Cameron’s much photographed niece Julia Jackson is coming into or going out of shadow when captured in 1867, the year of her marriage to Herbert Duckworth. Her resemblance to her daughter Virginia Woolf (those big eyelids) adds a shiver of uncertainty.

Bringing together Cameron’s work with that of the American photographer Francesca Woodman (who killed herself at the age of 22 in 1981), the curator Magdalene Keaney suggests in Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In that the two women are connected by their interest in creating pictures of angels (National Portrait Gallery, £35). As with other proposed links – both worked for a decade and a half or less, both started their careers when given cameras by family members, neither was celebrated during their lifetime, both were fascinated by Greek sculpture and umbrellas (oh, and both were women) – the correspondence is more mechanical than illuminating. Cameron’s angels are dimpled darlings snuggling towards the lens. Woodman’s fugitive figures – strips of flesh spreadeagled in the framework of doors – are heading for escape.

Despite the artificial yoking, the exhibition version of Portraits to Dream In, shown at the National Portrait Gallery earlier this year, helped to make the case first put nearly a hundred years ago by Roger Fry that the gallery would do better to stock up on photographs than go on buying mediocre canvases. It also illustrated the gallery’s double purpose: imaginative and documentary, with Woodman’s self-expression, her catching of things on the wing, and Cameron’s more deliberate composing. The wonder is to see Cameron at once shackled and breaking free, both Victorian and visionary. In setting out to ‘arrest all beauty’, she betrayed herself with a verb. Captured by her galumphing enthusiasm, some felt seized by the hand of a photocop and experienced the long, swaddled sitting as imprisonment. ‘I’ll come back soon and see what is left of you,’ Tennyson told Longfellow as he abandoned him to the camera. Browning, forgotten by Cameron as she rushed to the next mission, was left ‘helpless in the folds of the drapery’. There was sometimes arrest in the result too: groups that look stuffed; effects that are emphatic rather than dynamic. Yet her trademark fuzziness can make figures look as though breath were in the air around them, and when she is suddenly simple, she plunges through generations. In the picture from 1864 that she considered her first success, seven-year-old Annie Philpot looks away from the camera, pensive, buttoned up in her coat, a schoolgirl parting in her hair. She might have come from the 1950s; she makes you think there is no such thing as a period face.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.