When I complain it is sexist, the men on the door think I am having a laugh. Every week before being allowed into a theatre I have to prove I’m not dangerous by opening my bag for inspection. Meanwhile my male companion is invariably waved through – though that bulge in his pocket could be a knife.

Thanks to Hannah Carlson, I now regard this ritual as part of a widespread garment plot. In Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close (Algonquin, £25), Carlson shows the ways in which pouches confer power: routinely sewn into male but not into female clothing, they have helped men make their way through the world, fully equipped, as if they were armoured vehicles or portable garden sheds. She stretches the p-word to its elastic limits, solemnly seeking out ‘pocket integrity’, ‘pocket bounty’, ‘pocket allotment’, ‘pocket equilibrium’ and ‘pocket aspirations’. Yet she triumphantly lands her points.

In an arch but meticulously executed drawing of 1870 a pocket bolsters the idea of quintessential boyishness. At the bedside of their sleeping son a young couple examine the live turtle they have extracted from his trouser pocket. The man (two-tiered moustache) looks waggish; the woman (flouncy gown) concerned. Their expressions say: what a delightfully naughty little scamp! A print from some fifty years earlier shows a youth in a Regency dress coat with swishing tails: fur cuffs and standaway collar; lounging attitude; shoe daintily pointed. Both sumptuous and sloppy, he completes his claim to being a fop by casually stuffing his hands into pockets.

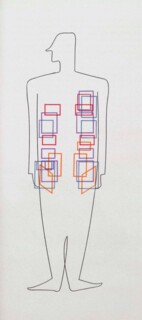

But Carlson’s main coup is to show that integrated pockets are aids to independence. In the 18th century, a man’s suit could become a portable cabinet, with accordion-shaped compartments for filing separate items, large side pouches for documents, a small chamber for a watch. Pockets generated the manufacture of miniature instruments: Thomas Jefferson was able to carry on his person sextant, scales and thermometer. In 1899 an article in the New York Times declared that, since the invention of pockets, ‘no pocketless person has ever been great.’

Women have not always been bereft. Pouches, tied around the waist, dangling among petticoats, and sometimes a whopping twenty inches long, enabled the sexual rummaging in Richardson’s Clarissa and probably prompted the nursery rhyme featuring Lucy Locket and Kitty Fisher, though Carlson explains that contemporaries thought that ‘pocket’ was code for ‘pimp’. Emily Dickinson persuaded her dressmaker to stitch a patch pocket, for pencil and paper, onto her white dresses; some seamstresses tucked a pocket into a bustle. Yet by the end of the 19th century most women were encumbered with bags and umbrellas and bits and bobs, or relied on someone else to do carrying. The discrepancy between male and female provision became a rallying point for Charlotte Perkins Gilman and other feminists. A 1915 suffragist parody, ‘Why We Oppose Pockets for Women’, declared: ‘We must not fly in the face of nature. The great majority of women do not want pockets. If they did they would have them.’

Carlson’s extensive research raises further questions. Are the objects in a pocket merely contents, or could they be called a collection? Crucially, when is a pocket not a pocket? Has it earned the title if it is not merely trivial – a decorative adornment on hip or tit which is too flat to hold anything but an emergency pill – but entirely pouchless, when it has dwindled into a flap? Can a trompe l’oeil pocket really be deemed ‘fraudulent’? Franco Moschino mocked Chanel by creating a trim tweed suit on which the pockets were upside down. Actually, most pockets are self-satirising as containers: men spill themselves all over the place because of gaping trouser pouches. Is this spilling an unconscious territorial claim? Are men particularly keen on pockets because they have vulva envy?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.