Two things you will see in Paris but not in London: the word ‘culture’ on a banner at a demo, and a major exhibition by an English artist and writer who has for half a century made the Brits roll their eyes at themselves. The events are linked by the partly British-designed Pompidou Centre. In October, staff went on strike, seeking assurance about their jobs when the building closes for repair next year. As protesters gathered in the square, inside the centre a retrospective of Posy Simmonds’s work was about to open.

Simmonds’s books and newspaper strips have been a compass for generations of British women, as sure a gauge of who and where they are as Marks and Spencer knickers. Measure waist and wobbles by the choice of thong or bikini, ‘full’ pant or ‘firm control’. Measure your degree of resignation and irony by the roll of Wendy Weber’s eyes. Check the outdatedness of your jaw and profession by comparing them to Wendy’s yuppie daughter, Belinda, razor-boned and working in posh catering. Sink alongside elderly Cassandra Darke, boiling with anger in a fur-trimmed flying cap. Warm to lying Matilda with her swivel eyes and Halloween mouth.

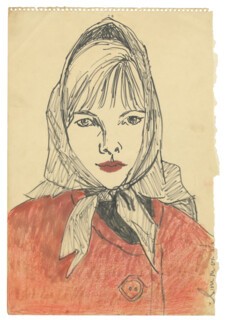

The feminism travels easily. Abroad, the extreme Englishness of detail – the guinea pig called Kenneth, the wails of down-from-London shoppers who can’t find a poussin in Tresoddit (Simmonds’s fictitious Cornish village) – adds nip. There is, though, a difference in cross-channel attention. The Pompidou exhibition, Drawing Literature (until 1 April), which opened two months before Simmonds was awarded the top prize at the Angoulême comics festival, is unprecedented in its extent and documentary meticulousness. The catalogue, edited by Paul Gravett and Anne-Claire Norot (with translations by Lili Sztajn), includes a substantial interview and swathes of unpublished material, including sketches made in Paris when Simmonds, as a student, sat for hours in front of a Manet in the Jeu de Paume and carried a tube of red paint with which to threaten sharp-suited gropers on the Metro. A self-portrait from 1963 shows the teenage artist on the cusp, turning from Cookham schoolgirl to Juliette Gréco: a headscarf, knotted Sloane-style under the chin, with a 1960s fringe poking out at the top; steady look, quizzical mouth.

England has been slower than France to realise that the term ‘graphic’ in front of novel is not (in the manner of ‘lady novelist’) diminishing, that it might actually signal a double dose of imagination. The speech that snaps out of these drawings (‘snog Ryan … bet you … he’d be like a donkey eating an apple …’) makes the dialogue of much contemporary drama look pallid. Some pictures create their own sonic boom. As a child, and mimic, Simmonds’s role in school plays was to supply the sound effects by voicing the creak of the stable door and the honk of the donkey. Her drawings have some comic splat – the !!!!s and ****s of the Dandy and the Beano with newer ‘Thunks!’ and ‘Gargs!’ They also reverberate graphically. A strangulating hangover expresses itself in a thick fuzzy font and out-of-control caps in a speech bubble with jagged edges. The heavy silence of the English countryside fills the title page of Tamara Drewe, in which a police van, light flashing, speeds through fields dotted with nonchalant black and white cows. Belted Galloways, as it happens. A Pompidou note explaining that these striped creatures have not been invented for comic effect but are a recognised breed alerts the English eye to how knitted the cattle look and how deceptive their stolidity is: they are killers. The strips are hand-lettered by Simmonds, who learned the skill of fitting speech to size as a student. She did so in a font of her own invention. She called it ‘Anal Retentive’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.