What colour was a Tyrannosaurus rex? How did an Archaeopteryx court a mate? And how do you paint the visual likeness of something no human eye will ever see? Far from bedevilling the artists who wanted to depict prehistoric creatures and their lost worlds, Zoë Lescaze’s book shows that such conundrums have in fact been invitations to glorious freedom. For nearly two hundred years the resulting genre – now known as palaeoart – has been a playground wherein tyrannosaurids, plesiosaurs and their fellows have not only illustrated scientific knowledge, but acted as scaled and feathered proxies for the anxieties of contemporary life. Lescaze argues that they should be seen as ‘roads to understanding our relationship to the past and our place within the present’. Despite these garish images of dinosaur combat and primeval cataclysm having held at best the status of kitsch, it is impossible to deny the extraordinary success of the genre. None of us has ever seen one, but who doesn’t know what a dinosaur looks like?

Palaeoart is inseparable from palaeontology, the scientific discipline it illuminates, and as interpretations of dinosaur anatomy and behaviour have changed, artists have generally tried to keep up with them. Debate still centres on how true to life it is possible to make representations of extinct creatures – how much soft tissue should they have? What colouration is plausible, given what we know about extant animal patterning? Historical palaeoartists typically incorporated the best knowledge of the time, so such questions can’t be completely ignored when looking at their work. But Lescaze deftly sidesteps this by making Palaeoart a history of images and artists, not a history of the accuracy of their art. Almost every image in the book became scientifically obsolete soon after it was created. ‘It is the imaginative nature of these works that makes them wonderful,’ Lescaze writes. ‘Rather than dismissing them as outdated, we should revel in their departures from reason.’

These images channel the spirit of their times and the character of their authors with a transparency their scientific pretension only underlines. Adorno wrote that the public’s fascination with dinosaurs was a ‘collective projection of the monstrous total state’ (‘people prepare themselves for its terrors by familiarising themselves with gigantic images’); keeping an eye on the wider historical context, Lescaze picks up on similar historical and psychological investments. Of the most widely repeated motif in 19th-century palaeoart – a plesiosaur and an ichthyosaur locked in deadly combat on the high seas – she observes that ‘the study of prehistoric marine reptiles began in the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, which were characterised by spectacular marine battles.’ In more surrealist mode, a painting by the Czech artist Zdeněk Burian showing a confrontation between a plated and spiked stegosaurian and a surprised-looking Antrodemus is given a psychological reading: ‘Violent arguments between Burian’s parents marred his childhood,’ Lescaze writes, transforming the prehistoric antagonists into monstrous grown-ups.

Images of violent combat between different prehistoric species are a constant in palaeoart. As the science of long-vanished creatures developed from unearthed bones, artists immediately forced these newly discovered beasts mercilessly to fight or eat each other, as if to make them extinct all over again. The very first notable attempt to depict prehistoric life, Henry Thomas De la Beche’s Duria Antiquior (c.1830), prominently features the ichthyosaur v. plesiosaur tableau that would become so common. In De la Beche’s watercolour, the dolphin-like former crushes the snake-like neck of the latter between vicious teeth. Lescaze describes the image as a ‘paean to primordial savagery’: ‘of the 34 animals swarming the revolutionary little painting, roughly half are feasting on or falling prey to one another in a riot of reptilian appetites.’

De la Beche, who lived in Dorset, was a respected geologist and clergyman. He was also a lifelong friend of the fossil hunter Mary Anning, whose excavations on the coast at Lyme Regis were instrumental in the development of palaeontology. Anning’s self-taught expertise, her subtle interpretation of fossils, and her many notable discoveries (including the ichthyosaur) made her one of the first authorities in the nascent discipline. But as a woman she couldn’t join the Geological Society of London and De la Beche, who was a member, had to present her findings in her stead. Credit for her discoveries was taken by others who published them as their own, and so while her work advanced the field, she was sidelined and became impoverished. De la Beche painted Duria Antiquior in the hope of helping his friend out of her dire financial straits, and based the denizens of his ancient sea largely on the creatures whose remains she had uncovered in the fossil-rich limestone and shale of Lyme Regis. When the painting became a print, the image sold widely, earning Anning a significant amount of money.

Although De la Beche’s well-informed tableau of conflict and predation became the genre’s template, the many 19th-century artists who adopted primordial subject matter were not all equally concerned with accuracy. Prehistory was frequently represented in what Lescaze calls ‘violent hellscapes’, and many of these early images recall not only the dragons and monsters of folklore and fantasy, but visions of hell itself, filled with writhing beasts that rend at one another as fires destroy the earth. In John Martin’s The Country of The Iguanodon (1837), a group of dragon-like reptiles slither and bite; in A. Demarly’s apocalyptic Eruptions of Poisonous Hot Springs in the Triassic Period (1883) a geyser of toxic gas spurts from a volcanic vent, while dead dinosaurs lie piled up in front of us.

Such images reveal a profound unease about the very idea of extinct, prehistoric creatures. In a Christian society, the precise place these newly discovered animals held in God’s creation was a source of debate and consternation. Were they antediluvian beings, who had been destroyed in the Flood? Did that mean they’d been wicked – undeserving of the salvation afforded other animals? Did they date from a time earlier still, a ‘pre-Adamic’ moment of creation? Or had they never lived at all, their bones having been placed in rocks by the Creator as a test of faith? In 1830, Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology had argued that the Earth was much older than the six thousand or so years suggested by scripture, and in 1859 Darwin’s On the Origin of Species promoted a new theory that scandalously linked all of organic life together through an iron law of competition and extinction. Meanwhile, the factories of the industrial revolution were issuing forth new, smoke-belching, roaring creations. The wild violence of much early palaeoart, with its images of frenzied consumption and environmental disaster, were symptomatic of these alarming uncertainties.

Alongside these visions of universal catastrophe, a more peaceful ancient world also existed. In much early British palaeoart, the dinosaur is dignified lord of creation not hellish dragon. These visions of a sublime prehistory can be seen as a transformation of Romantic landscape painting, and in them dinosaurs appear as the just rulers of a natural kingdom. Britain was newly in its imperial pomp, and Lescaze argues that ‘palaeoart held a mirror to an expanding empire, reflecting its shining ideals of progress and well-ordered sovereignty … As Britain forged a new, imperial identity, prehistoric animals became beasts of immense metaphorical burden, conveying both the optimism and anxieties of an era.’ In the wake of Darwin’s revolution, dinosaurs started to find their place as part of the great evolutionary chain of being that led towards the human species and the light of reason. In Georges Devy’s engraving The Trumpet of Scientific Judgment Sounded (1886), a thinking scientist, heralded by an angel, is attended by a patient herd of mammoths, pterosaurs and frog-like dinosaurs – newly discovered, they await the classification that will assign them places in the grand scheme that science had started to discern.

Though Lescaze does reproduce a number of popular images of prehistory – including some marvellously florid tea cards, postcards and popular prints – Palaeoart is not about the pop cultural reach of the dinosaur (W.J.T. Mitchell’s The Last Dinosaur Book deals with that subject).* The paintings Lescaze writes about were high art, and closely allied to contemporary science. But this doesn’t mean they weren’t aimed squarely at the public. And no single artist in the genre’s early years had the ambition and popular influence of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins.

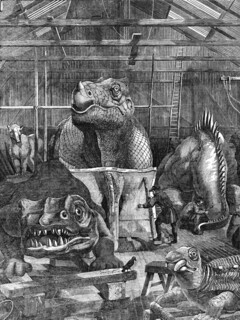

The great dinosaur sculpture park that Hawkins made for the reopening of the Crystal Palace in 1854 is perhaps the most famous example of palaeoart. ‘These days most schoolchildren can draw or identify a dozen different dinosaurs,’ Lescaze writes, ‘but hardly anyone in the world knew what they looked like when Hawkins unveiled his concrete zoo.’ A zoological illustrator who had worked for Darwin among others, Hawkins worked on the Crystal Palace dinosaurs with the scientist Richard Owen, who had coined the word ‘dinosaur’ (from the Greek deinos, ‘terrible’, and sauros, ‘lizard’) in 1841. Theirs was the first attempt to revivify dry fossil bones and even drier scientific discourse for a large public. Though the sculptures are now known for their inaccuracy – with the bipedal Iguanodon, the talismanic beast of early English palaeontology, recreated as a slothful and rhinocerotic quadruped, its thumb-spike misplaced on the tip of its snout as a horn – they were faithful to the most recent science, and are rendered in startling anatomical detail. Hawkins’s concrete and brick beasts included ichythosaurs, pterosaurs, a hunched and baleful Megalosaurus and a half-submerged mosasaur, all of them arrayed on a series of artificial islands and lakes. Created as a new attraction after the Crystal Palace was moved to South London, it was a life-size diorama representing the magnificence of prehistoric Britain, and the public were captivated. Forty thousand visitors attended the opening day. Scientists sniped that his creations involved too much conjecture, but Hawkins’s work was celebrated and satirised across the press.

For the crowds that flocked to see them, Hawkins’s dinosaurs were a revelation. ‘The sensational statues acted on viewers in the same way frescoes affected early Renaissance worshippers,’ Lescaze suggests. ‘Just as Giotto rendered the life of Christ viscerally real and immediate … Hawkins vividly conveyed prehistory to broad audiences.’ The artist’s work continued after the grand opening, and he was engaged in creating a new set of dinosaurs when the Crystal Palace Company’s shareholders decided his creations were too pricey, and terminated his contract. Hawkins worked only intermittently from then on, but with moments of great success, in both Britain and America. Nothing on the scale of his Crystal Palace work was ever undertaken again.

Hawkins believed with a ‘fierce conviction’ that new scientific knowledge of prehistory ‘should not only be accessible to the wealthy and well educated’, but to all. Having already redefined the public perception of prehistoric life, he would make one further critical contribution, arguably even more important: the piecing together of a complete Hadrosaurus skeleton at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, in 1868. Articulated dinosaur skeletons are now a standard part of the museum experience, but Hawkins’s hadrosaur was the first dinosaur to be reconstructed in its natural posture, ‘a 14-foot-tall reptile standing in midstride as though it could charge out of the building’. It was a sensation, ‘an astounding, utterly alien sight’, and the crowds that came to see it were so large that the Academy charged an entrance fee in an attempt to keep the numbers down.

In 1850s Britain, the growth of palaeontology and the worlds it uncovered were seamlessly folded into the British imperial imaginary; in late 19th-century America, the fossil hunters and their quarry rapidly became inseparable from the myths and realities of the American West. Lescaze likens the US palaeontological scene to ‘a bar-room brawl’, and for the American palaeontologists ranging over the deserts of the western states in search of bones, the horned and frilled Triceratops took on the air of the vanishing American bison, while tyrannosaurids began to absorb the features of the near extinct cowboy (Disney’s recent animation The Good Dinosaur casts them in this role; the Ray Harryhausen-animated creature feature The Valley of Gwangi also contains a mash-up of dinosaur and Western themes).

The artist who breathed life into the vast numbers of dinosaur fossils collected on the outlaw frontier was Charles Knight. Born in New York in 1874, and severely visually impaired from birth, he had to hold his face close to the canvas as he painted (by the end of his career he was registered blind). He spent his youth as a habitué of New York’s zoos, where he learned to draw living animals, and of the American Museum of Natural History, where he learned to draw dead ones. Eventually the museum’s scientists began to commission him to paint prehistoric creatures, and his work caught the eye of the museum’s president, Henry Fairfield Osborn. Osborn became Knight’s main patron, and in the late 1890s he revolutionised palaeoart for the new century, recasting the sluggish behemoths of the 19th century as alert and agile creatures set in vibrantly naturalistic landscapes.

Artistic mores had also changed since Hawkins’s day; Knight’s work draws on the bright palette and lively movement of Impressionism. His experience of painting zoo animals informed his depictions of scale and muscle; it was, he said, important to remember that dinosaurs were once ‘living breathing creatures, existing in an atmosphere of colour, light and shade’, just like the animals we know. His 1897 painting Laelaps shows two of the eponymous predators in tumbling, aggressive combat; it set a precedent that continues to define the active, intelligent dinos of the contemporary imagination.

Though Lescaze shines new light on them, the images of Hawkins, Knight and their followers in Europe and the US are comparatively well known. Better known still is their legacy: generations of children have grown up with pictures and models, and latterly films, that draw heavily on their work. But there is another tradition of prehistoric imagery which hasn’t had such reach, having been ‘locked into obscurity by the legacy of the Cold War’: the palaeoart of the Soviet Union and the countries in its sphere of influence. The final sections of Lescaze’s book are dedicated to this almost completely unknown tradition.

A precursor to Soviet palaeoart is to be found in the State Historical Museum in Moscow. Victor Vasnetsov’s huge mural of early human life, Stone Age, painted for the museum between 1882 and 1885, shows dramatic scenes from the Palaeolithic era – bacchanals, frenzied hunts, fire-making and cooking – in a broadly realist mode. Vasnetsov’s vast painting is certainly extraordinary and, insofar as it shows Stone Age life as a recognisable if primitive human existence, it is visionary. But things become even more interesting after the Revolution.

Palaeoart flourished under the Soviets, and the high status of scientific research in the USSR lent the pictures legitimacy as well as a rare degree of freedom. ‘The intrinsically unknowable, mysterious nature of prehistory enabled works of palaeoart to elude the requisite propagandism of Soviet artwork devoted to contemporary subjects,’ Lescaze writes; palaeoartists ‘dodged the scrutiny directed at professional fine artists, and were able to create less didactic images favouring open interpretation over instruction’. The most influential of them was Konstantin Flyorov, whose career was sponsored by the State Darwin Museum in Moscow. An irascible and domineering man, his images of prehistoric life are less concerned with scientific veracity than with the creation of boldly imagined worlds. Painted in a lurid expressionist style, Flyorov depicts a brace of Triceratops battling a wheeling, roaring Tyrannosaurus, while a caravan of Baluchitherium stalk a parti-coloured fauvist landscape; his Prehistoric People (1939) represents early humans looking out from the darkness of their cave towards a sunlit landscape – an allegory of the future life likely impermissible in any other context. The prehistoric subject matter, Lescaze writes, allowed for ‘greater subtlety, narrative ambiguity, and nuance’ to enter the work; the paintings by other Soviet artists such as Alexei Komarov and Andrei Lopatin reproduced here bear this judgment out. The opalescent dreamscape of Mai Miturich-Khlebnikov and Viktor Duvidov’s Late Cretaceous Landscape of the South Gobi was painted in 1986, in the months after Gorbachev admitted that the Soviet miracle had long been a mirage. It is an astonishing image of a dissolving reality, its vast beasts wading in a golden meadow of flowering waterlilies, oblivious in their gilded dream, just before the reality of extinction struck.

Lescaze doesn’t bring us all the way to modern palaeoart. Instead, she ends with the 1970s work of Ely Kish, whose painting is unusual in its focus on extinction. Featuring decayed corpses, dried-out skeletons, and parched creatures dying in the desert, and drawing on an increasing anxiety about environmental damage, Kish’s work showed the great dying of the dinosaurs. It’s a pertinent note to end on, and it’s the one thing that’s beyond debate: however they were feathered, furred or coloured, and whether they were sluggish or nimble, dim-witted or highly intelligent, all these dinosaurs are utterly dead, for ever. Prey or predator, they are all extinct. Adorno suggests that the dream of a living dinosaur signals the hope, born in guilt, that other living things might survive the disaster humankind is inflicting on the natural world, even if we don’t. If the cosmic memento mori provided to us by these strange paintings of resurrected ancient creatures was once oblique, it is not any more. We are already well into the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history, and it is being caused by us. The comet isn’t coming, it has arrived.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.