Culebras, or ‘snakes’, come in a twist of three, tightly plaited and bound by ribbon. Their history is obscure: perhaps the style arose because parsimonious cigar-factory bosses wanted to restrict the cigar-rolling torcedores to an allotment of three cigars a day; perhaps it was an innovation from the tobacco plantations of the Philippines, intended to yield a moderately faster curing time. Either way, a culebra is a striking thing – a plump and fragrant braid in the box, but a crooked and root-like appendage in the hand.

They were Jacques Lacan’s preferred smoke. The first room of Lacan: L’Exposition at the Pompidou-Metz (until 27 May), an extensive show dedicated to Lacan’s legacy in the visual arts, includes some captivating film of his infamous séminaires. Owlish behind spectacles, his leonine mane swept back, Lacan speaks in expressive, measured tones, a gnarled culebra, long gone cold, clasped between his fingers. Freud smoked incessantly, including during sessions with patients; he is rarely pictured without a cigar, of the conventional style, in hand. It makes sense that Lacan, whose labyrinthine rereading of Freud is as revolutionary in its own way as Freud’s original work, should inflect the master’s habit with his own idiosyncratic, convoluted style.

Alongside letters, photographs, early publications in Surrealist journals and other fragments of Lacan’s personal and professional life, a dried-out plait of culebras has been placed in one of the vitrines that provide the exhibition with a biographical timeline of its subject. It sits beneath a framed set of the brightly coloured cords that Lacan would loop and snarl together as a means of investigating the ‘topologies’ of the psyche that he developed to a point of truly Gordian complexity in his later work. Psychoanalysis has always liked twisting three things together: from Freud’s unconscious, preconscious and conscious, later refined into id, ego and superego, through the Oedipal nexus of the parents and the child, to Lacan’s own Borromean knot of the Real, the Imaginary and the Symbolic.

As puzzling and complex as they are, the colubrine knots, hitches and vector diagrams found throughout Lacan’s texts are essential to tracing the winding pathways of his thought; he was a visual thinker in a way that Freud was not, and continually explicated his ideas using both his own schematic diagrams and by calling attention to works of art. From his early text on the mirror stage – the crucial moment of ego-formation when the infant glimpses its reflection in a mirror – to his later elaborations on ‘the gaze’ and his regular appeals to trompe l’oeil and anamorphosis in the understanding of psychic processes, many of Lacan’s most influential theories circle around vision and the visual image. The voluminous transcriptions of his seminars are studded with so many paintings that they themselves present an imaginary exhibition, hung with Holbein’s Ambassadors, Cézanne’s still lifes, the legendary grapes of Zeuxis and curtain of Parrhasius, Velázquez’s Las Meninas and countless others. ‘The artist,’ he wrote, ‘always precedes [the analyst].’ Great works of art had already illuminated even the most deeply hidden features of the phenomena he sought to describe.

The Pompidou show, carefully curated by Marie-Laure Bernadac and Bernard Marcadé, is billed as the first specifically dedicated to Lacan, which is surprising. But the influence of Lacan’s ideas on art, artists and art criticism has been so pervasive that on walking round the show it becomes clear that we have been attending Lacan-themed exhibitions for decades – or at any rate, exhibitions full of works that stand in easy relation to Lacanian concepts, put together by curators who deal, at some level, with Lacan’s categories and concerns (you can’t get away from ‘the gaze’, for a start).

Bringing this influence out into the open, Lacan: L’Exposition makes Lacan himself the subject and presiding spirit of the exhibition. The format is rigid, with each room given over to a different concept; some ideas have an abundance of works to illustrate them, while others are restricted to just a couple of rather oblique pieces. Wall texts in each space provide key quotes, with curatorial glosses for the uninitiated, though many of these shed little light. There is rarely a simple way to paraphrase Lacan.

The artworks do this job much better, and with more reach and subtlety. The arrangement is loosely chronological, and after the opening biographical section, the first room is dedicated to le stade du miroir. Alongside Marcel Broodthaers’s Miroir M.B. M.B. M.B… ., from 1971 – a false diptych consisting of two white rectangles, one completely empty, the other marked miroir and crowded with scrawled ‘M.B.’ initials – and a savvy Michelangelo Pistoletto piece playing mirror, light and image against each other to truly confusing spatial effect, the centrepiece is Caravaggio’s monumental Narcissus, borrowed from the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome. ‘Blindly rapt with desire for himself’, as Ovid has it, Caravaggio’s boy bends over his reflection, one hand dipped sensuously in the water, a phallic bare knee thrusting forward into the centre of the image. ‘In love with an empty hope’, Ovid writes, pointing us towards the complex of desires, projections and misidentifications that attend the ideal image of the ego, a complex which stirs in infancy as the baby glimpses its spectral double. Across the room, a short clip of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver plays on a loop. ‘You talkin’ to me?’ De Niro’s Travis Bickle asks his reflection in a mirror, looking around. ‘Well, I’m the only one here.’

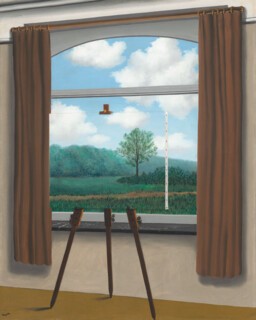

The problem with having a painting such as Narcissus open your show is that hardly anything else can match it. But the exhibition, which features more than three hundred works, makes a good recovery. Some of it is just what one would expect to see in a show dedicated to psychoanalysis: a lot of Louise Bourgeois; some evilly erotic Hans Bellmer drawings and an alarming photograph from the poupée series; a few superb Magrittes (La Condition humaine from 1933 in particular looks very grand in this context; Lacan’s formative connection to Surrealism is usefully emphasised throughout); a number of Duchamps, including one of the reconstructions of The Large Glass and his vicious little Female Fig Leaf; works by Claude Cahun, Brancusi and Dalí. As well as the Caravaggio, there are paintings by Zurbarán (Saint Lucy, holding out her eyes on a platter) and Velázquez’s Portrait of the Infanta Marguerite Thérèse. (Las Meninas, like The Ambassadors, doesn’t travel.) Contemporary artists are well represented, especially in the second half of the show, which moves away from the more widely known Lacanian notions such as the gaze, l’objet petit a and le nom/non-du-père towards ideas which only a more dedicated reader might previously have encountered in any detail: la femme, la voix, ‘Il n’y a pas de rapport sexuel,’ jouissance and others. A modest but suggestive piece by Sharon Kivland is a highlight: Envois V (2022) consists of seven imaginary love letters to Kivland from Lacan, supposedly written on postcards and sent from Munich in 1958. It is one of the few works in the show that neither refers us to Lacan nor merely illustrates his ideas but, by reframing his words as clumsy, amorous billets-doux, takes him in hand and interrogates his thinking.

The aims of the exhibition are twofold: to explicate Lacan’s ideas through art works, and to demonstrate how fertile Lacanian ideas have been for artists (or Lacanian-ish ideas, at any rate). But there is always a third cigar in the bundle – you could call it the unconscious, the lost object, the objet petit a. And in Metz, the absence at the centre is Lacan’s own art collection.

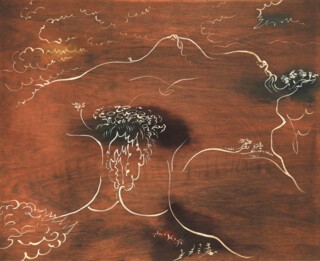

Lacan certainly bought art, but it seems that his collection was broken up; there is no complete list of what it contained (a scholarly article on the subject suggests it was mostly composed of images of fentes – ‘slits’). The curators have been able to locate just three of the many works known to have belonged to him: a large abstract painting by the Chinese artist Zao Wou-Ki (Lacan started studying Chinese languages and literature during the wartime Occupation and later befriended Zao) and two pieces that ensure Caravaggio doesn’t get the last laugh – a wooden panel by André Masson, and the painting it was made to conceal: the font of all fentes, Courbet’s L’Origine du monde.

It never ceases to amaze me that Lacan himself owned L’Origine du monde, which he acquired in 1955. In part, this is because it is odd to think that such an important work could so recently have been anyone’s private property, but mostly because Lacan’s ownership of it sends us right to the centre of the psychoanalytic adventure. In combining the visually erotic with a title that transforms it into an image of the maternal – indeed, the pagan and mythological maternal absolute, the mother of everything – Courbet’s confrontational picture presents the very image of Oedipal desire. It is the model of the lost object, suggesting the generative, creative interior of the maternal body while also stirring feelings linked to the act of sex. (There is a straightforwardly Freudian logic to the fact that Masson’s concealing panel recreates the image, but transforms it into a landscape, with forests, hills and rivers – a barely reconstructed translation of Freud’s notorious remark that feminine sexuality was a ‘dark continent’.) The painting belongs to the history of erotic and private art, and it was commissioned and owned by men, but what Courbet’s magnificent provocation means is that they were being asked to gaze sexually into the maternal cunt. The artist certainly precedes the analyst here, and it is easy to picture Lacan before the painting, cigar at his lips, considering what it was he was looking at, and what was looking back at him. One can sense the power and grandeur of L’Origine du monde behind Lacan’s mature ideas, as behind an elaborate screen. It may seem to disclose, in a single simple image, the whole shabby secret of his baleful science. Moreover, Courbet offers a pre-emptive riposte to Lacan’s insistence that the subject is always organised around an absence, a gap, a fente at the centre: this origin is not a place of lack but of creation’s plenitude, not an empty space but the site of pleasure and joy. No wonder he asked Masson to help him hide it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.