I pray every day that super-intelligent aliens will come to earth and save us from self-destruction, so when an 800-metre-long cigar-shaped object was found to have hurtled into our solar system I felt a stirring of hope. It was picked up on 19 October by the Pan-STARRS (Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System) at the University of Hawaii’s Astronomical Institute. Its speed and the direction of its orbit indicated that it had come from outside our solar system – making it the first object we’ve ever identified as an arrival from interstellar space – and that it would eventually leave on its way towards the constellation of Pegasus. It was initially thought to be a comet, but soon reclassified as an asteroid: comets are icy rocks formed on the outskirts of solar systems and produce a tail of gas and dust when they fly close to the sun, but the cigar had no tail. It is also deep red in colour, the result of its irradiation by cosmic rays over millions of years. The astronomers at the University of Hawaii gave it the name ‘Oumuamua’, which reportedly means ‘scout’, but which, according to the one Hawaiian dictionary I could access online, refers specifically to ‘the foremost soldier or the front line in battle’, giving the cigar a more sinister complexion.

Oumuamua is ten times longer than it is wide. Nothing else we’ve observed in our solar system has this shape. Asteroids aren’t cigar-shaped, spaceships are. There have been several UFO sightings of cigar-shaped vessels, including one seen over Paris in May. Many Oumuamua-watchers have also noticed the similarity between Oumuamua and the alien spaceship in Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama, a cylindrical vehicle that turns out to be hollow and filled with strange machinery, including hybrid mechanico-biological robots. Rama creates an artificial gravitational field by spinning along its axis; Wired published a piece a few days ago showing how Oumuamua, which is also spinning, is doing the same thing (though its gravitational field is much weaker than Earth’s, and isn’t really a gravitational field at all but ‘apparent weight’). Someone joked on Twitter that Oumuamua was piloted by aliens who had intended to make contact, but that having noticed that the Flat Earth International Conference was taking place on 9-10 November decided to give us a miss. Flat Earthers believe the Earth is flat and that scientists and governments have conspired to keep this truth from us. Apparently some of them also believe that the ‘spherical Earth theory’ was seeded by aliens who want to stop us from developing actual space travel technology, which is ironic, if that’s the word.

In Rendezvous with Rama, a survey vehicle called ‘Endeavour’ is sent to explore the alien ship. Members of its crew touch down on one end of the cylinder and find an entry hatch, then cautiously begin looking around the cylinder’s vast interior, a highly organised patchwork landscape of mosaics, artificial waterways and giant electrical components. The novel contains some of the most hallucinatory descriptions in science fiction of an encounter between humans and a technology they find incomprehensible: there are fields of wire wool and beds of crystal-studded sand, crackling metal columns and curious robotic crabs that pick up detritus and carry it into Rama’s canals. I’m not saying Oumuamua will definitely look like that close-up, but even if it turns out not to be an alien spaceship, surely we should explore it if possible: it’s the first piece of macroscopic interstellar material we’ve been aware of, and it’s still relatively close by. Happily, scientists are trying to work out how we might go about it. Some of them even think it could be managed. Members of the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, a proto-institute whose goal is ‘to enable both robotic and human exploration and colonisation of the nearby stars’, have published a paper of recommendations for how we might catch up with Oumuamua – they call it Project Lyra.

One difficulty is that Oumuamua has an excess velocity of 26 km per second (‘excess velocity’ denotes speeds greater than the speed required to escape the sun’s gravitational pull). The fastest object humanity has ever built is Voyager 1, a probe launched by Nasa in 1977 which is still sending information back from beyond Eris, and it had an excess velocity of 16.6 km per second. Another difficulty is that Oumuamua is getting further and further away. The longer it takes us to launch the probe, the more speed we’ll need to intercept Oumuamua, and the longer the mission will take. One of the possibilities considered by Project Lyra is using SpaceX’s Big Falcon Rocket, a launch vehicle powered by methane-fuelled engines whose design was unveiled in September, which should be operational by the early 2020s. The plan would be to have the rocket fly towards Jupiter, and use the planet’s gravitational field to fling it in the direction of the sun for a close solar fly-by (or ‘fry-by’), then on towards Oumuamua. The Project Lyra people calculate that an excess velocity of 70 km per second should be achievable with this technique, and that the ship would intercept Oumuamua in 2039 at a distance from Earth of 85 AU (Astronomical Units – the average distance between the Earth and the Sun, around 150 million km). The second option Project Lyra considers is a fleet of lightsail-powered probes. Lightsail-powered craft are currently under development by a company called Breakthrough Initiatives, and would fly using solar pressure, or multi-megawatt laser beams, directed at giant mirrors. Project Lyra envisages a ‘swarm’ of hundreds of thousands of lightweight sail-powered probes launched in Oumuamua’s direction in five years’ time.

There are so many signs that we’re on the cusp of a new dark age. Religion is on the rise, as are the numbers of believers in astrology and conspiracy theories, and average IQ is falling: according to one psychology professor at the University of Amsterdam it has fallen among Westerners by as many as 14 points since the beginning of the 20th century. The pace of technological development is slowing. A Flat Earther called ‘Mad’ Mike Hughes had planned to launch himself into the atmosphere in a homemade rocket on 25 November in an effort to prove that the Earth is flat, but was prevented from doing so by the US’s Bureau of Land Management, which of course only reinforced his theory that there’s been a cover-up. This trend is discouraging. Whether or not we’re capable of commanding swarms of laser-sail powered space probes in ten years’ time will depend on what kind of people we’ve become. Play our cards right and the Flat Earthers will be able to send their own mini-probes up into the atmosphere, without putting their lives in danger, and resolve their doubts for good. Get it wrong and we’ll forever be the dunces of the universe, pointed at and mocked by aliens as they pass through in their cigars on their way to somewhere more sophisticated.

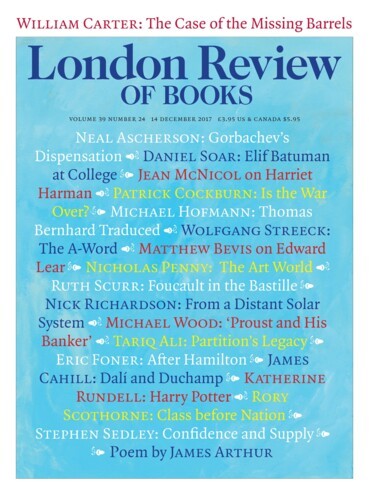

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.