Part of the magic of grimoires resides in the word itself: ‘grim’, with its aura of frost and severity, opening onto that chasmic vowel, a playground for demons. Exactly when or why manuals for conjuring spirits came to be known by this name is unclear, but the convention was well established in Europe by the Middle Ages. ‘Grimoire’ is French for ‘grammary’, a book of grammar: it may have been adopted because the manuscripts were often in Latin; perhaps it was a term used more generally of abstruse, esoteric texts. Certainly, grimoires had been around for many hundreds of years before they were known as such. There are grimoires among the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, which date from the fertile period of cross-cultural exchange in Hellenistic Egypt between the second century bce and the fifth century ce, and many of the best-known European grimoires contain vestiges of the ancient religions of Egypt, Greece and Sumer, though most were authored by nominal Christians who made a great show of piety in their writing.

‘Solomon, the Son of David, King of Israel, hath said that the beginning of our Key is to fear God, to adore Him, to honour Him with contrition of heart, to invoke Him in all matters which we wish to undertake, and to operate with very great devotion, for thus God will lead us in the right way.’ So begins the best-known grimoire in its best-known edition: the Key of Solomon, as assembled in 1889 from a number of sources by Samuel MacGregor Mathers of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The Key of Solomon represents the invocation of spirits as a perilous activity to be attempted only by the most devout. It requires a nine-day period of preparation, during which body and soul are conditioned by fasting, sexual abstinence, ritual bathing and prayer. The magician must fabricate, or otherwise obtain, elaborate tools, such as a pair of garters made from the skin of a stag and inscribed in the blood of a hare, then stuffed with green mugwort and the eyes of a barbel fish. Incense is to be concocted from bat’s blood after the magician has exorcised the bat in the names of a few dozen angels. Earthen vessels, parchment and wax for candles must be made ready according to precise instructions, along with the ‘lamen’ and ‘Holy Pentacles’: metal discs engraved with symbols supposed to strike terror into the spirits and force them to obey.

The long list of demands made by the Key of Solomon is unlikely ever to have been satisfied in full. The magician who fails to conjure a spirit can have only him or herself to blame: are you sure that bat was well and truly exorcised? Luckily for the aspiring magus, there are more easy-going grimoires, or less finicky spirits. The Grimoire Encyclopedia, compiled by David Rankine, a historian and modern practitioner of magic, contains an entry for every grimoire we know about, with a short gloss on the text and bullet points describing the salient features: date, sources, influences, spirits conjured, magical tools. Lazier magicians may favour the Theurgia Goetia, an English grimoire of 1641 that requires only four tools – crystal, girdle, pentacle of Solomon, ‘Table of the Art’ – but provides access to hundreds of spirits. The Book of Saint Cyprian: the Sorcerer’s Treasure (of which there are multiple versions, the earliest from the 17th century) contains a longer and more rarefied list of tools – black-handled knife, boleante (a rod with nails in it for chastising demons), censer, magic mirror, three kinds of wooden rod (boxwood, hazel and olive), a steel knife and a sword – but the demons it allows you to invoke are far fewer. Perhaps more unusual ritual tools get you a higher class of demon? The complete set of magical tools required by the grimoires, along with references to the spells in which they’re used, is included in an appendix to the encyclopedia. We find ‘Hedgehog: used in a charm to attract a woman’, along with hundreds of entries for oils of different types and their respective uses: ‘Oil (unspecified) … rub on a rooster’s bottom and it will not mate, on its head and it will not crow’; ‘Oil (Elderberry): used in lamp mixture to make people appear to have black faces’.

Mathers, the Golden Dawn’s founder, assembled his edition of the Key of Solomon from manuscripts written in French, Italian and Latin, the oldest of which dates from the 16th century. He censored from those manuscripts anything that smelled of ‘Black Magic’, out of concern, he claimed, for the souls of those into whose incautious hands the book might fall: ‘Let him who … determines to work evil, be assured that that evil will recoil on himself and that he will be struck by the reflex current.’ He notes the existence of two grimoires, the Grimorium Verum and the Clavicola di Salomone ridolta, that are ‘full of evil magic’.

Despite his admonition, the Grimorium Verum (or True Grimoire) is now readily available. Its tone is quite different from the Key of Solomon. There is no solemn preamble on the paramount importance of faith and contrition, and the instructions for fashioning the ritual apparatus are much less demanding. The Key of Solomon, though it is effusive on the proper format of the conjuration ritual, has less to say about who or what might be summoned as a result. Not so the Grimorium Verum, which lists a dozen or so ‘superior’ and ‘inferior’ spirits, with a brief description, in the manner of Top Trump cards, of their appearance and powers, and the sigils used to summon them. The names of the superior spirits – Lucifer, Belzebuth, Astaroth – are familiar, but readers may be surprised to learn that they do not inhabit hell: Lucifer and his inferiors live in Europe and Asia, Belzebuth in Africa and Astaroth in America. Among the inferior spirits is Bechaud, who has power over ordinary rain and snow as well as ‘rains of blood, and of toads and other species’. He requires a walnut in sacrifice. Mersilde has the power to transport anyone in an instant to wherever they like; Morail can make you invisible; Frutimière prepares feasts and sumptuous banquets; Clisthert grants power over night and day. Spells put these spirits to work for unvirtuous ends: ‘To Make a Girl Dance in the Nude’, ‘To Have Gold Pieces, as Many and as Often and Every Time You Want’, and so on.

What kinds of creature these spirits are and whether they can be considered good or evil is a controversial matter. In an essay included in his edition of the True Grimoire (2010), Jake Stratton-Kent, a prominent practitioner of and advocate for grimoire magic until his death last year, traces the evolution of the superior spirits, whom many think of as demons, from pre-Christian (and not especially evil) pagan deities. ‘Lucifer’ comes from the Latin for ‘light-bearer’, a sobriquet commonly applied to Venus (and on occasion, Mercury). Belzebuth is better known as Beelzebub, the ‘Lord of the Flies’, which would appear to be an insulting mistranslation into Hebrew of the name of a Philistine god: the original ‘would have involved a form of Baal, a common title of Phoenician and Canaanite gods’. Stratton-Kent suggests a correspondence with Jupiter, following the grimoires, which frequently connect Belzebuth with the planet. ‘Astaroth’ is the Hebrew name of the goddess known in Greek as Astarte, an important Phoenician lunar goddess. As for the inferior spirits, many of them have the characteristics of Elementals (spirits of water, earth, fire and air), widely held to be neutral agents who could be used for good or evil purposes.

Stratton-Kent points out that versions of a ritual known as the ‘Art Armadel’, which is contained in a number of the grimoires including the Grimorium Verum, also appear in the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri. The ritual centres on an act of scrying: the inducing of a vision in the magician, who gazes into a reflective surface, flame or lamp. In the case of the Grimorium Verum, the surface is a mirror on which the magician has written four sacred names with the blood of a pigeon. A striking similarity between the Art Armadel as contained in the grimoires and the version found in the papyri is the summoning of an intermediary, whom the magician must call on before being granted access to the spirit he or she is attempting to contact. In the Grimorium Verum, this figure is an angel, Anael; in many of the examples from the papyri, it is Anubis, the dog-faced god of the underworld, who invites the spirits to a feast where the magician can question them.

In his excellent history, Grimoires (2009), Owen Davies, a professor at the University of Hertfordshire who specialises in the history of magic, stresses the importance of the Greco-Egyptian papyri in the early history of the grimoires, contrasting them with the earliest magical inscriptions and papyri from the time of the pharaohs. In the pharaonic material, the focus is on health and protection, whereas the magic of the later papyri aims more at satisfying the magician’s desires for financial gain, social success and sexual conquest. Davies also emphasises the impact on European grimoires of the Moorish invasion of the Iberian peninsula. The city of Toledo, after it was retaken from the Moors by Alfonso VI in 1085, became a centre of Arabic scholarship among Moorish converts to Christianity and Christians ‘Arabised’ by centuries of Moorish rule. Many texts in Arabic, including works of magic, were studied and translated into Latin by the clergy of Toledo Cathedral and began to spread across Europe. As a result, the city acquired a reputation as a hotbed of necromantic activity. (Black magic tourism, in the form of walking tours taking in the haunts of templar monks, necromancers, sorcerers and alchemists, flourishes in Toledo to this day.) As the French priest Hélinand de Froidmont observed in the early 13th century, one found ‘the liberal arts in Paris, the law in Bologna, medicine in Salerno and demons in Toledo’.

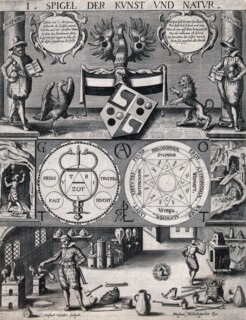

Arabic magic focused on harnessing the powers of stars and planets by calling on their associated spirits and angels at astrologically propitious moments. The best-known Arabic magical text, the Picatrix (in Arabic the Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm, ‘The Aim of the Sage’), instructs the magician in the manufacture of talismans imbued with the power of astronomical bodies. This involved elaborate apparel (helmets and swords) and animal sacrifices: a white dove for Venus, a black goat for Saturn. The influence of texts such as the Picatrix can be seen in the Key of Solomon’s insistence not only on similar apparel but on the importance of precise timing of magical operations, which must be performed on the day, and at the hour, of the presiding planetary spirits: ‘In the Days and Hours of Saturn thou canst perform experiments to summon the souls from Hades,’ whereas ‘the days and hours of Mercury are good to operate for eloquence and intelligence; promptitude in business; science and divination.’ Tables are provided that associate a planet, angel and archangel with each hour and day of the week.

The rites of exorcism were another important influence. The first half of the Key of Solomon makes for thrilling reading, in part because the intensity of the ritual increases dramatically with each attempt at summoning. The magician is instructed to stand at the centre of his laboriously prepared magic circle and recite the first conjuration. If nothing happens, the ‘suffumigations’ are renewed, the magician holds up his knife and proceeds to ‘strike the air’, then there is a confession, a prayer and a further conjuration, this one louder and more solemn, including more exhortations and holy names. If the spirits still fail to appear, the magician reveals the Pentacles, holds the knife aloft and bellows a further conjuration: ‘Behold anew the Symbol and the Name of a Sovereign and Conquering God, through which all the Universe fears, trembles and shudders.’ The ritual of exorcism, as documented by the 16th-century exorcist Girolamo Menghi, follows exactly this format, with a sequence of prayers, conjurations, recitations of holy names and dramatic gestures that intensify in pitch in proportion to the possessing spirit’s reluctance to be exorcised. Not only did exorcism provide a ritual template, it provided logical and moral justification for the practice of conjuration: if it were possible to wrestle demons into obedience by calling on superior spiritual forces (and the Church said it was) then it was possible to do this outside an exorcism; if it was not only possible, but right and good to manipulate and interrogate demons (and the Church said it was), why would it not be right and good to do so from the comfort of one’s own magic circle?

The Church authorities took against magic, however, and in the 16th century instituted a crackdown. One arm of the suppression was, of course, the witch trials, but it is important to realise that the consumers of grimoires, the majority of whom were male and literate, were (most of the time) not the same people as those tried as witches, who were usually neither of those things. Most of the women tried as witches weren’t actually witches, whereas those tried as heretics for the use of grimoires were – most likely – using grimoires. One reason for the particular notoriety of the Key of Solomon is that it appears more often than any other grimoire in the legal records of defendants.

The backlash against grimoires was a consequence of the rise in literacy levels across Europe, which had extended the pool of grimoire readers beyond the monastic and courtly communities, where they had been freely studied and shared, and their spells practised in secret. Davies argues that the Church itself was partly to blame for the surge in literacy. Rates of education among the clergy had been very low in the early 16th century. In 1551, the bishop of Gloucester had found that 168 priests in his diocese were unable even to repeat the Ten Commandments, and court records from the time are full of complaints from parishioners about boozing, womanising village priests. The shabby reputation of Catholic priests became a contributing factor in the rise of Protestantism, and many Protestant churches distinguished themselves from their Catholic counterparts by insisting that their priests obtain a university degree. The Catholic Church, in response, created seminaries for the compulsory education, and re-education, of its priesthood. But by improving the literacy levels of its clergy, the Church enabled its priests to abuse their position of spiritual authority by getting hold of grimoires (which they could now read) and charging parishioners for extra services involving the conjuration of spirits.

Rates of education among the rest of society improved during the same period, in tandem with the rise of print. Many of the ‘cunning folk’, rural practitioners of traditional magic, were able to extend their menu of services by getting hold of print copies of grimoires. Shepherds, who had a reputation in rural communities for being wise and educated (possibly because the quasi-masonic fraternities to which many belonged insisted on a level of literacy for membership), made money on the side by charging for spells cast from printed grimoires. We know from court records, as well as from correspondence with booksellers and accomplices, that there were increasing numbers of amateur magicians, too: they were usually artisans, tradesmen or farmers who had made enough money to educate themselves, and who bought grimoires and practised magic, both experimentally and for profit. Catholic authorities reacted to the spread of printed grimoires in Europe by publishing, from 1559 onwards, the papal Index of Prohibited Books, which banned all works of instruction in the magical arts. But this turned out to be another self-defeating measure that did more to excite interest in the prohibited books than anything else.

According to Davies, a shift in the official view of magic was precipitated by the investigation in 1678 into a plot to poison Louis XIV. As the recently created Paris police force probed the seedy underworld of the poison trade, it became clear that the suppliers of poisons – or ‘inheritance powders’ – were often also magicians, whose services were sought not only by the poor and uneducated but by the aristocratic elites. Male courtiers were drawn to black magic by promises of great wealth, while female courtiers paid magicians for love powders and potions supposed to boost their powers of seduction or ensure the faithfulness of their husbands. The confessions of two sorceresses, one a tailor’s wife, the other the widow of a horse dealer, exposed a close-knit network of magicians, priests, fortune-tellers, shepherd herbalists and apothecaries. Raids on their homes turned up stacks of grimoires. Twenty-five were found in the possession of a cunning woman who was said to have more learning ‘in the tip of her finger’ than others acquired in a lifetime, and who lived ‘as man and wife’ with another female magician. Among the more than forty churchmen arrested in connection with the poisoning plot was Étienne Guibourg, an elderly priest who confessed to performing black masses using the belly of a naked woman as an altar, and whose library contained numerous papers detailing rituals for invoking the demon Salam.

The exposure of this underworld led Louis XIV to order the passing of a law that aimed to quash those who ‘follow the vain professions of fortune-tellers, magicians or sorcerers’. Louis’s edict described magic as a foolish belief rather than a genuine diabolic force and made it clear that the law’s purpose was the protection of ‘ignorant and credulous people’ from con artists who claimed to possess supernatural powers. Over the next few decades, similar legislation appeared elsewhere in Europe reflecting this change in perspective. Grimoires remained popular among the general population throughout the Enlightenment and beyond, but the official view of them shifted from ‘instruments of heresy’ to ‘immoral manuals of superstition’. Today, practising grimoire magic won’t land you in prison, but talking people into paying you to enlist the services of demons on their behalf might.

Davies’s Art of the Grimoire, a survey of grimoire illustrations from the earliest papyri to the present day, provides a visual companion to this history. Many of the sigils, circles and seals from medieval and Renaissance grimoires are familiar from film and TV: they have been a stock trope for decades of horror movies (a grimoire bound in human flesh and ‘inked in human blood’ plays a central role in the Evil Dead series). The Hollywood grimoire is so firmly embedded in our cultural imagination that grimoires which don’t conform to stereotype appear all the more striking. Pages from a 13th-century manuscript titled Ars Notoria, sive Flores aurei contain distinctive plant forms in red ink. A ribbed and phallic cactus with protruding hair-thin fronds rises from the mouth of a demon. Three circles connected by a column contain the rippling, enfolded forms of what might be mushrooms. The magician is instructed to meditate on these diagrams while intoning the prayers written alongside them. An illuminated plate from a 14th-century French translation of the Llibre dels àngels, a manual for the invocation of angels by the Catalan friar Francesc Eiximenis, shows a red-winged angel leading a man away from a devil shaped like a black jackal, who walks upright on long legs with clawed feet. A scarlet tongue pokes rudely from its horned head.

Davies makes sure to remind us that although print expanded access to grimoires, it also stoked the zealotry of the anti-magic brigade. The title page of Peter Binsfeld, bishop of Trier’s Tractat von Bekanntnuss der Zauberer und Hexen (1592), a popular denunciation of witchcraft, bears a woodcut showing a group of witches: one kneels as she gropes the crotch of a devil, another dangles a baby’s head in a cauldron of boiling water, a third conjures a hailstorm with a pitchfork (or is it a broomstick?). A hand-coloured print broadsheet from 1586 reports on the problem of devils, who were blamed for terrible storms over Ghent: the accompanying illustration portrays the devils in the form of dragons, wrecking churches and uprooting homes. Davies includes the title page of a print edition of Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft from 1584, alongside one of its illustrations, a magic circle composed of the usual sigils, circles, pentagrams and magical names. Scot was an MP, and his book was intended as a condemnation of the foolishness of magic, but it contained so many conjurations, exorcisms, talismans and sigils that it became a popular grimoire in its own right.

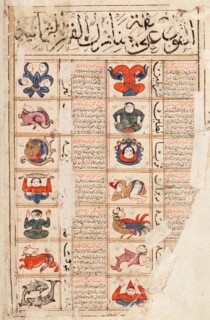

Art of the Grimoire encompasses grimoires and grimoire-like texts from beyond the Western tradition. Davies includes the Great Pustaha, a book of magic employed by the Batak magician-priests of Northern Sumatra. The cover of the 19th-century example included in the book is elaborately carved in black wood, while the pages are folded and glued: they open like a concertina to reveal a collection of incantations and spells illustrated in red and black ink. In the pages reproduced here, an insect monster with bristling limbs, a curling, fern-like tongue and skin tattooed with geometric mosaics is shown surrounded by imps in pointy red hats. (Imps around the world wear pointy hats, it seems.) Davies has found spellbooks, talismans and oracle bones with strangely rune-like inscriptions from China, and lavishly illustrated catalogues of yо̄kai (spirits) from Japan. Among the wonders from the Islamic magical tradition are books of djinn – such as the ‘Red King’, depicted riding a lion and called on to protect the home from snakes – and works of astrology: in the Kitāb al-Bulhān (‘Book of Surprises’), the ‘angels of the seven heavens’ are represented by curious human-animal-plant hybrids. Belief in a multitude of non-human entities, and in the ability of humankind to forge relationships with them via magical words and images, appears to be almost universal – and wherever these beliefs have co-existed with literacy, we find grimoires.

We are lucky to have Davies’s books, yet it is possible to read them and still feel as though the mystery of what exactly people were doing, and are still doing, with grimoires has not been resolved. What actually happens when someone invokes a demon? If nothing, then why are these beliefs so tenacious? Stratton-Kent and Rankine made grimoire magic part of their daily lives not because they were persuaded to do so by cynical wayward priests, but because they found in the grimoires a powerful source of religious experience – and there are many people like them, as a quick look online will confirm. The books of Stratton-Kent and Rankine are written less for historians than for other grimoire magicians who claim to be interacting with demons. Maybe demons do exist (I wouldn’t rule it out). Or it could be something like a kind of willed schizophrenia. Alan Moore once said that the magician is ‘trying to drive him or herself mad in a controlled setting, within controlled laws’, which could be the beginning of a convincing explanation of what the magician is doing, though it’s probably not one most magicians would agree with. There is a mechanism for interaction with something here, even if it’s only with our own imaginations. A book by a psychologist that took seriously the experiences of grimoire magicians (as Jung did with people who claimed to have seen UFOs) would make a fascinating accompaniment to Davies’s work.

I don’t feel compelled to communicate with demons, but I experienced several synchronicities in the course of writing this piece that made me feel, at times, as though something supernatural was trying to communicate with me. Working in the library one evening, I looked up from my desk to see, on the shelf immediately opposite me, a copy of Der Dämon by the German writer Arthur Luther. Weird, but probably nothing. On the second occasion, again at the library, I had just written a line about clergymen charging for extra services involving demons when I found in the gents a business card for ‘Mr Madiba’, a local witch doctor providing magical assistance in love and business to anyone willing to pay for it. A coincidence. But what about this one? I was on the Tube one morning, listening to a podcast by a psychiatrist interested in the occult. He described invoking one of the demons said to be useful in financial affairs and asking it for some money – as an experiment, of course. The following day he was queuing in a shop when the person in front of him dropped a £20 note. No one else seemed to notice, and he felt, he said, as though time had stopped: he had to decide whether to take the money and run, or do the decent thing and return it to its rightful owner. He gave it back. The psychiatrist was making a point about the dubious ethics of grimoire demons, but that’s not why I’m retelling the story. While I was listening to him, a man standing in front of me on the Tube dropped a £5 note on the floor.

What was going on? I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was playing with me, or wanted me to play with it – and I’m afraid I took the bait. At home I got the True Grimoire down from the shelf and turned to the spell ‘For Hearing a Pleasant Music’, which is one of the easiest to perform. You inscribe in a circle the sigil of Klepoth, a spirit who can make you see ‘all sorts of dances, dreams and visions’ as well as help you cheat at cards by whispering to you what’s in your opponent’s hand as you play. I carefully inscribed the sigil, then recited eleven magical words. ‘Afterwards,’ the spell says, ‘you will hear pleasing music.’ I waited a while, but nothing happened. The sigil of Klepoth is quite tricky to draw, so I gave it another go, thinking perhaps I’d made a mistake. I drew the circle, I inscribed the sigil, I intoned the magical words. I waited. Nothing happened.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.