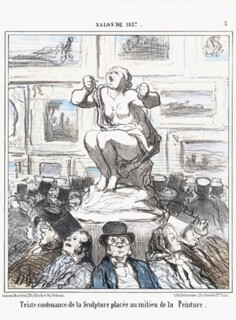

A Daumier lithograph of 1857 shows a marble statue on a plinth coming alive in the midst of the busy Salon. She clenches her fists and bawls in sheer frustration. No one hears her. No one sees her – and that is the reason for the ‘triste contenance de la Sculpture’, as the caption has it. In an out-turned circle, the top-hatted Parisian art-lovers turn their backs on the plinth, gawping instead at the paintings packed dado to ceiling on the Salon’s walls. Eleven years earlier, in his ‘Salon de 1846’, Baudelaire had sardonically wondered ‘why sculpture is boring’. Three-dimensional manufacture – ‘brutale et positive comme la nature’ – satisfies only hicks and savages, the critic suggested. More advanced minds will not be content with objects that can be approached from all angles and thus fail to supply us with a personal artistic viewpoint. Painting, with its single perspective, ‘exclusive et despotique’, is more properly the language of the imagination.

Daumier – who became a hero for Baudelaire – could feel for the marble on her plinth because he had kept company with sculptors from his youth in 1820s Paris, most notably Auguste Préault, a fiery radical pursuing a difficult course in a fine art highly dependent on official patronage. Daumier, the son of a penniless glazier-turned-playwright, headed instead for the unrespectable trade of press illustration. From the age of 21 he knocked out at least an image a week for the combative leftist editor Charles Philipon, becoming a master of snap metaphors, startling crops and chiaroscuros and suchlike tools from the picture-maker’s kit. Yet behind the lush surfaces of his lithography, a 3D artist is always at work.

The figures in his pictures have been assembled on a mental modelling stand, one on which he distils and recomposes his observations rather than transcribing them straight from the object. To deliver the picture entails isolating one aspect of a body he already understands in the round. Early on, he conceived his figures in stout heavy blocks, squeezed to this satirical end or that in accordance with phrenological interpretations of character. In 1832, aged 24, he started actualising some of these interpretive studies in clay: six such grotesque heads are exhibited in the thrilling précis of Daumier’s career on view at the Royal Academy until 26 January, along with two later forays into modelling, a fragmentary relief and a figurine of Ratapoil, the twisted bogeyman intended to lambast the resurgent Bonapartism of the mid-century.

In between, Daumier’s mind-sculptures exchanged weight for dynamism. The Fugitives relief of 1848 or thereabouts shows the heroic nude entering his repertoire: in no way a careerist yet dreamily ambitious, he would have drunk up the comparisons to Michelangelo that critics have since invoked. But already he was looking beyond that schema, starting to conceive each figure as a verb (climb, carry, fall etc): an inclination in space given transient visibility. Wonderful pen drawings from his middle age bring out the attitudes of clowns or lawyers from seedbeds of freely wandering line, wash being gently applied to the paper wherever body volume or body interactions suggest themselves. He seems to home in unerringly on those inner prototypes, so sure in poise, so empathetically inhabited.

Why should we think about the prototypes, treating Daumier’s art as a two-tier operation? Because the exhibition points us towards such a fractured set of surfaces. Of course lithography, compliantly transmitting every nuance of his crayon, remained his base of operations over more than forty years of hand to mouth picture production, during which he cast his eye over three revolutions and two intervening autocracies. Equally, the pen and watercolour work of the early 1860s – a time when the ageing artist needed to produce saleable pieces because Philipon had modernised his paper and dropped him – presents a mannerly, obliging face.

But some fifteen years before that, Daumier started reaching for oils, and his dealings with this high art medium expanded the fault lines opened up by his clay experiments. He tends to approach oils as if a matrix of free brushwork could deliver his ideas to him as lucidly as lines drawn with crayon or pen: but the paint keeps sliding the thought out of his hands, transmuting it into something less precise in meaning and possibly more glamorous. Sometimes he falls in with that process, as in his largest canvas, an Ecce Homo of c.1850 that swaggers with a woozy, Goyaesque bombast. But often he fights it – most furiously in a Man on a Rope done about a decade later, in which the slathered impastos have been scoured, sanded and hacked about with blades. Baudelaire’s argument is inverted: the brute, unruly paint is coming between Daumier and the clean sculptural concept in his imagination.

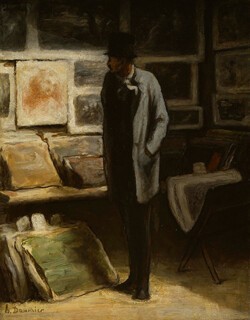

Stand far enough back, and the image just about recomposes into another inclination in space, another way a figural mass might suggest a city or a terrain around itself. Elsewhere, it might be a heavy-burdened laundrywoman and her small daughter crystallising the quaysides of the Seine, or a hovering-to-pounce collector leafing through a portfolio in a print shop. (Catherine Lampert and Ann Dumas, the exhibition’s curators, have shrewdly foregrounded the genial art-world banter in Daumier’s wide subject range, rather than, say, his sneers at 19th-century feminism.) Daumier’s figures summon up times as well as spaces: none more so than the railway passenger looking out of a window in A Third-Class Carriage, man and window effectively devising a visual character for modernity through their stark receding repetitions. Alternately, there are his melancholy, self-referential pasts: the old street clowns whom no one still cares to watch, or Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, forlorn spirit and squat flesh, adrift in a Parisian’s fantasy of desert Spain.

That this exhibition is full of irresistible jokes as well as stabs of pathos almost goes without saying, particularly when it is near impossible to draw a line between Daumier’s own wit and that of Philipon, who composed many of the captions. Laughter shrinks historical distance. The body-centred politics of this art, with its instinct that every rhetorical burden should be weighed on the shoulders of working men and women, continues to communicate. Or is it the communication breakdowns that inspire, the flailing battles with paint that seem a foretaste of later modernist heroics? Think further about Daumier’s politics or his aesthetics and the historical strangeness returns: the unique circumstances in which this quiet, dreamy, noble-minded hack played off the brash new medium of lithography against high art agendas. Think further about the mental operations involved in doing so, and you fall back to reflecting on the strangeness of genius.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.