Broad shoulders retreating down a gangplank: my mind’s eye rests there, after reading two new books about Paul Gauguin. The gait is springy: this passenger pushes away from the others; he strides off. The ground on which he alights is Peruvian, then French, Danish, Panamanian, Martinican and Tahitian, until finally a rowing boat anchors and his feet wade ashore on rocky Hiva Oa in the mid-Pacific Marquesas. I note the force in those shoulders though the face is half-averted. Gauguin appears a lone unit, careering across a globe vexed by European empires. The wake behind him still churns and confuses – his crisp figures in golden oranges and browns set against brooding greens and violets, his sinister pottery, his burnished wooden ‘idols’ and slogan-incised planks (‘Soyez mystérieuses’). One source of the confusion being that we have yet fully to detach ourselves from that era.

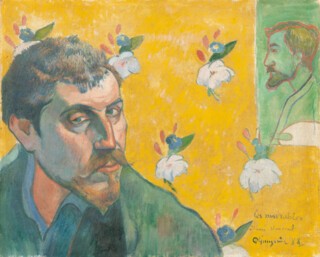

Before there are books there are bodies, and it’s to a body that these books return the reader. ‘Tall, dark-haired, swarthy of skin, heavy of eyelid and with handsome features, all combined with a powerful figure’: this is how Gauguin struck an observer who met him in 1886 in a Breton fishing village. The head of Pont-Aven’s artist gang was then in his late thirties. Five years later Mette, his estranged Danish wife, found herself faced with a ‘grizzled eagle’, according to Sue Prideaux, with a ‘great hooked beak of a nose’. He ‘exuded virility’. The title of Prideaux’s biography, Wild Thing, runs with Gauguin’s boast of being ‘a savage from Peru’. (He had spent his childhood years in Lima, where his widowed mother had relations.) During an early stint as a merchant marine his nose got broken somehow, but Gauguin was a tough: he could claim never to be ‘put out of my road by others’.

He was a tough who philosophised. ‘Life has no meaning unless one lives it with a will,’ Gauguin wrote not long before it ended for him in 1903, his frame giving way after 54 years of hard exertion. In his heyday he had been – as the Parisian journalists liked to repeat – a ‘Hercules’ with a sweeping range of labours. Prideaux surveys them: here was a master of fencing, a player always ready to strike up on mandolin or harmonium, a navvy briefly excavating the Panama Canal, a carer for one ailing painter (Charles Laval) in a Caribbean beach hut and for another (Vincent van Gogh) in a two-up-two-down in Arles, a government draughtsman in a Tahiti planning office, an anti-government political satirist, a cook ‘proud of his skill in making a good French omelette baveuse, runny in the middle’. Forging his own path on limited funds, Gauguin roved the social scale. After their return to France in 1855, his mother became the kept woman of a cultured financier who helped her son move from seamanship to stockbroking. Years of high earning on the Bourse ended with the banking crash of 1882. By this point Gauguin was 38 and a family man with four children. He tried his hand as a rep for a French tarpaulin business in Copenhagen before being reduced to pasting up bills on the Parisian boulevards for five francs a day. From that point onwards, he was forced back on his art. ‘A queer mix-up’ was Gauguin’s take on the change in his fortunes, as he looked back on six turbulent years doing what he could to make painting pay. A buoyant review, nonetheless: ‘I stand on the edge of the abyss, yet I do not fall in.’

His footing in the world may have been insecure, but he was dextrous. Nicholas Thomas, whose Gauguin and Polynesia encompasses much that preceded Gauguin’s arrival in Tahiti in 1891, observes how swiftly he mastered diverse techniques: lithography in 1889, for instance, and before that woodcarving and ceramics. Entering a pottery in Paris for a few weeks in 1886, Gauguin conjured up, ‘at a rate of nearly two pots every day’, irregular convoluted vessels that drew on his recherché knowledge of ancient Peruvian ware – innovatory achievements later to be hailed by Degas, Matisse and Picasso. No less deftly, he had nine years earlier carved and burnished slick marble busts of Mette and their first son, Émile. The handiwork in oils – that finicky, almost nervously precise hog-brush hatching that remained his default mode – began somewhere around the time of his meeting with Mette in 1872. Describing a quiet agricultural landscape dated to the following year, Thomas judges it ‘extraordinary’ that ‘a novice, quite literally a Sunday painter with limited time and no formal tuition’ could produce something so ‘fully resolved and perspectivally complex’. He notes that this canvas nods – not least in its title, Working the Land – to the work of Pissarro, one of the Paris independents in whose art Gauguin’s mother’s benefactor was taking an interest. I would build on that. In mapping Gauguin’s ‘wild’ zigzag pathway, his dealings with Mette and with Pissarro – both relationships emerging much at the time he first took to painting – offer telling co-ordinates.

Mette, the Danish tourist introduced to Gauguin in a Right Bank restaurant in 1872, was equipped with unflappable self-confidence, backed by a family in the Copenhagen elite. Two handsome strong people matched off – first as lovers and parents, and then, after Gauguin lost his foothold in the Bourse, as wrestlers over cash. Both fought quite low while holding fast to their respective rectitudes. Life together became unsustainable after a dozen years, though they continued to correspond. Gauguin’s letters reveal that the marriage was as integral to him as the art which helped wreck it. He butted himself against Mette – his persecutor, his allegiance, his hope against hope. Posting from Paris to Denmark in 1888, he declared class war: he was one of those who must rely on ‘the fruits of their labour’, opposing himself to a bourgeoise who could lean on unearned income. ‘You do not like art,’ he wrote. ‘So what do you like? Money.’

Gaining no ground, Gauguin went on firing at Mette after relocating to colonial Tahiti. ‘The women here admire my wife’s photograph,’ he wrote to her in 1893. ‘I’ve told them she is dead.’ Among the admiring ‘vahine’ was probably the 13-year-old Teha’amana, whom he had recently painted lying belly down, naked on a bed with her eye on the viewer. In a letter ending ‘Kisses for you and the children’, Gauguin sent Mette a description of the painting, with a taunting ‘this-isn’t-what-you-think-it-is’ exegesis that he said might be ‘necessary’ after Mana’o Tupapa’u was dispatched back to Europe to be exhibited. The girl’s eye was inwardly fixed, he argued, on a ghost he had inserted to hover behind her, an oil painter’s approximation of a Polynesian woodcarving.

The provocations – the didactic mystifications that started with that foreign-language title, indeed the sex tourism itself – were the sharper because he was scratching at his own sores. You don’t need to warm to Gauguin personally, as Prideaux does, as Thomas doesn’t, to sense that an inner dislocation directed his jagged behaviour, perhaps also resonating in his jittery brushwork and grotesque ceramics. Here in Tahiti, did he remain a ‘savage’? Or was he a grounded citizen, a ‘courageous colonist’ harassed by the thieving ‘native’? (His choice of words as editor of a local journal.) He was both and neither: the indigent ‘greatest modern painter’ (his own words again) and the failed paterfamilias; it became difficult to bear, and in his fiftieth year there was a suicide attempt. It was only in 1901, after his final journey, to Hiva Oa, that a certain composure seems to have set in. Many who had met him back in France – notably van Gogh – looked up to him as a leader. But he had been backing onto a ledge, in retreat from his own reflection.

Compare his own first mentor. Pissarro, eighteen years older, was more fully placeless: a Jew born in the Danish West Indies who retained his original passport throughout a career spent in France. Gauguin records in the memoirs he started writing on Hiva Oa the abiding respect he felt for him. That respect was not reciprocated, however, as Pissarro’s letters to his son Lucien make clear. Why should it not have been? ‘Working the land’ – figures interacting with a certain generous terrain, a vision dear to the painter of paysannes fruit-picking in the Île-de-France – was a theme to which Gauguin equally liked to return: the Caribbean women porters depicted during his 1887 stay in Martinique echo those in Pissarro’s earliest canvases, and later, by Pacific shores, Gauguin again portrayed islanders sustained by an environment that was properly theirs, albeit with less muscular effort. Each déraciné yearned for a stable arcadia, each would have been aware of its precarity.

It’s true that Pissarro’s diffusions of dapple contrast with the chunky compartments of hot colour that Gauguin came to favour, but that was not what caused the former’s disapproval. No, what he rejected was the presumption that a global citizen could deliver a global art; what he also suspected was a touristic frivolity about the experience of the persons observed. Pissarro castigated the Vision of the Sermon (1888) – Gauguin’s canvas in which a Jacob wrestling an angel manifests itself in the scarlet collective imagination of a Breton village congregation – for pick-’n’-mix appropriation: ‘He swiped all that [the components of the vision] from the Japanese and from Byzantine painters.’ It was a dalliance with religion that represented ‘a step back’, he thought. Did Gauguin really see and believe as those coiffed Bretonnes did? Was he not a metropolitan modern? This mere ‘sailor’s art’, this ‘bricoleur’s’ ragbag, looked still worse in 1893, when Gauguin, on a two-year return from Tahiti, exhibited canvases in Paris that yoked iconographies by turns Buddhist, Hindu, Christian or would-be Oceanic (that ghost) to material sketched during his initial stay in the colony. The two painters faced off, as Pissarro related: ‘He told me … that the young would find salvation by replenishing themselves at remote and savage sources. I told him that this art did not belong to him, that he was a civilised man and hence it was his function to show us harmonious things. We parted, each unconvinced.’

Each argument here, as I see it, still has grip. Even as it was in 1893, artists remain torn between the invigorating jangliness of world culture and the urge to compose a clear personal melody. Was Pissarro fair to Gauguin? Prideaux and Thomas each have nuanced answers. The former – a fulsome scene-setter (‘Silk and satin dresses susurrated swishily, sexily’ and so on) – keeps to the promise of her preface ‘not to condemn, not to excuse’, but Wild Thing is driven by her partisan engagement with her man in all his manliness and underpinned by her confidence as a tour guide to the intellectual styles of the Belle Époque. (She has also written lives of Munch, Strindberg and Nietzsche.) Thus she can expound the ‘Symbolist-Synthetist’ notions aired at soirées held by Mallarmé that Gauguin would attend, and defend Gauguin’s ‘point that worldwide historical references were designed to infer [she must mean ‘imply’ – where are Faber’s copyeditors?] universal human interconnection’, all the while insisting that no programme could constrain a painter who believed that ‘art must be totally free to roam wild.’

But her most intriguing argument for Gauguin’s work is that he kept nagging at a distinctive obsession. A lifelong puzzlement: what may the other, over there, be thinking? Or as Prideaux introduces it, with reference to the portraits of his children, ‘the impenetrable discontinuities of consciousness’. Gauguin sometimes guesses specifically. Behind the sleeping head of his second son, Clovis, ‘the rich cobalt-blue wallpaper … has become the night-coloured sea of his dreams.’ Beyond the Breton parishioners is the vermilion in which their imaginations might be swimming. In the violet darkness above Teha’amana lurks the crudely modelled bogey that causes her to stare in fright – or so Gauguin tried to claim. For these are additive tactics in picture-making, and therein lies their shakiness. We see one chunky body of strong pigment and we see another of contrasting hue and we are held by the optical vibrancy of colour itself, rather than sent off on a poetic journey. Gauguin seems often to settle for this. He piles on symbols from wherever. They add to the sumptuousness. They don’t signify. Eh bien. Soyez mystérieuses.

In this sense, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? – the nearly four-metre-wide ‘last testament’ Gauguin composed before attempting suicide in 1897 – may be considered, Thomas proposes, ‘a success as a painting, but a failure as a work of art’. Its blue-greens, golds and browns ravish the eyes but there’s a mismatch between the lofty speculations promised by the title and the Tahitian figures to which the hot pigments attach. ‘What the painting is emphatically not, is any sort of representation of Oceanic culture, belief or identity,’ Thomas states as a lifelong student of those matters. An Australian-born anthropologist, he reviews the extant art-historical commentary on Gauguin’s big frieze and remarks on ‘the insensitivity to local voice of the ostensibly progressive northern hemisphere academy’. Although, as this suggests, Thomas’s pitch is more to the campus lecture theatre than to Prideaux’s general readership, his insights are fully as humane.

He opens up a two-way conversation. Here was a European modern interacting not with doomed passive victims of colonialism, but with Polynesian contemporaries fashioning their own forms of modernity. The fabrics, forms of building and everyday dealings that Gauguin recorded in the South Seas testify to communities tackling globalisation with flair and resilience: more, communities that nurtured their own artistic interpreters. Thomas notes that while visiting a museum on a stopover in Auckland in 1895, Gauguin may well have encountered the innovatory woodcarvings of Tene Waitere, produced for colonial patrons; he illustrates an astonishing example, combining the ‘classic dense design’ of Maori art with naturalistic portraiture. Gauguin’s own ‘faux-devotional’ ironwood idols converge in appearance. What should we make of this? Thomas is left wondering whether in Gauguin and Polynesia he has been describing ‘a meeting, or just a crossing of paths’.

His evidence pushes either way. The incomer’s political instincts were erratic: now statist-conformist, as we’ve seen, now subversive – in his last years on Hiva Oa, Gauguin distinctly and honourably stood up for indigènes against empire. His sexual behaviour looks at the very least slobbish. (Prideaux absolves him of passing syphilis to his partners, citing a recent chemical analysis of his teeth which shows that he wasn’t given the standard treatment for the disease; Thomas is not so sure.) Yet the light-commitment ‘marriages’ that Gauguin entered into were unexceptional in Tahitian society, and one of the adolescents involved later remembered him merely as un coquin, a rascal. Thomas thinks it probable that dialogue with Teha’amana about Tahitian beliefs prompted Gauguin to insert the tupapa’u behind her body: there was, in other words, genuine exchange. But, as Thomas repeatedly complains, sifting the data remains difficult because Gauguin was such an unreliable witness. He liked to cover his tracks as a painter and was often his own worst advocate. I can’t but side with Thomas: this would have been a tiresome guy to meet, however thankful I feel for the rewards his art offers.

Combine Gauguin’s own screeds about his intentions with those of the art historians: set them against the canvases themselves – and what can you then conclude? That Where Do We Come From is ‘essentially incoherent’. That Manao Tupapa’u ‘simply cannot be made coherent’: that ‘this painting, if not Gauguin’s whole output, is contradictory in the deepest possible sense.’ In this ruminative riposte to quickfire commendations and condemnations, Thomas has contrived one of those brow-furrowing counterintuitive claims designed to raise appreciative hmms in a seminar. But no, professor. Category mistake. Those canvases are as coherent as their size, priming and oil medium will allow. Paintings and those who make them are concrete entities around which criticism flits and flickers. We come back to mere bodies.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.