The Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum is now open. It is home to the museum’s scientists and its dried, bottled and otherwise preserved collections of specimens. The recently completed ‘cocoon’ is an eight-storey-high sprayed-concrete storage space. The path to it (for the moment at least) is by way of the dark galleries with hardwood drawers and display cases of Waterhouse’s main museum building. You pass under the white bulge of the cocoon, and find yourself standing beside the towering glass wall that encloses it. The dramatic transition from one style of building to another seems to carry a message about one kind of biological science replacing another. A feature is made of internal windows that let you look into working laboratories. They were impressive but empty on the morning I was there. What you see – the machinery that has mechanised DNA sequencing, the microscopes and the computers – fits so nicely with the elegant modernism of the building, designed by the Danish firm C.F. Møller Architects, that the ensemble suggests a work of art: a Damien Hirst medicine cabinet, say. But that emptiness was doubtless an accident of timing. The theme throughout is activity. There are new tools and techniques, and the attitude to the public is pressing in its openness.

The layout of the building programmes the visit. A lift takes you to the top and walkways that follow the curves of the cocoon wall lead you down and around from one didactic, interactive station to another. Behind the foot-thick cocoon walls lie the collections. Temperature and humidity are adjusted to keep safe the contents of the countless drawers of beetles, butterflies and spiders and the sheets of pressed plants that make up the museum’s entomological and botanical collections. You get to see the inside of the cocoon through internal windows, but it is sealed from intruders: the carpet beetle is one of a host of enemies that must be kept at bay. So in one way the symbolism is confused. A real cocoon protects a developing, living creature. Here everything that is kept is also dead.

Among the displays there are video clips; they remind you that there is more than one species of museum. For example, while art museums buy, solicit, borrow, or gracefully accept additions to their holdings, the staff of the Natural History Museum go out into the world to pick and trap new material. The museum buys things too – they’ve just raised £150,000 to purchase Jean-Marie Cadiou’s collection of 230,000 hawk moths – but much of what accompanies the new displays comes from field trips. They may take a scientist to a distant jungle-covered mountain or to a local bog. Once there foliage is snipped, soil sampled and bugs trapped. Clips from video diaries show you the tools of the trade (light traps for moths, pitfall traps for beetles, lots of local newspapers to press plants), tell of tribulations (insect bites, typhoons) and give a notion of what is achieved: hoards of beetles, flies, plants and so forth brought home. The clips are just one aspect of the museum’s eagerness to show what they do and how they do it, to put aside the pejorative vocabulary (‘fusty’, ‘old’) and replace it with that of modern science. There are even windows through which you can watch day to day operations in the cocoon. I’m not sure, were I on the staff, that I would relish the demands this makes. A flashing light invites you to press the button and talk to the woman you see mounting plants, but she is busy and doesn’t really look as though she would welcome the interruption. In any case, what she is doing is well described in a video loop.

Many of the specimens are old – some go back to the 18th century, to the founding collections of Hans Sloane and the first scientific explorers – and their importance is acknowledged. The emphasis, however, is on the museum’s role as a working scientific institution. As far as public spectacle goes, the part of the museum’s collection that is housed here has one great advantage: the contents are unusually beautiful. Stuffed birds and beasts, their skeletons and skins, and the jars of faded creatures in the Spirit Collection housed in another part of the Darwin Centre are now too easily contrasted with footage of living examples to be quite the things of wonder they once were. Butterflies and beetles, on the other hand, are often nearly as bright in their preserved state as they were in real life – and quite as brilliant as they are in their portraits on porcelain, textiles, or in the margins of books of hours. Some of the cases are as pretty as a Meissen plate or a length of embroidered silk. Dry, faded plants attached to herbarium sheets – flowers and buds, the fronts and backs of leaves, young and old foliage – have the ordered charm of illustrations in old herbals. Once in a while you are distracted by the projected image of a living insect as it makes its way across one of the surfaces you touch to get more information.

The clips in which scientists speak about their work are direct and interesting. You become aware of the distinction between natural history – the collecting and labelling of specimens – and taxonomy: the establishment of evolutionary relationships. Taxonomists have been notoriously argumentative; theirs is a descriptive, interpretive discipline that didn’t allow much in the way of experimental confirmation until DNA analysis arrived. Not that DNA resolves every dispute. One of the little video lectures refers to a study which began as a search for the genetic differences that distinguish two strains of a British orchid; it turned out that visible divergence in the plants was not yet clearly identifiable in the genome. One imagines that this piece of work was picked out because it shows that the monitoring of diversity still matters, even when most of the recent research pointed up in a new botany text will have arisen from experiments on one species – thale cress. The new gene-sequencing laboratories one sees through the interior windows don’t preclude the need to collect and describe. The answer often given when the value of taxonomy is questioned – does it really matter at just what point a new twig began to sprout in the tree of life? – is that only mapping diversity will allow us to monitor environmental change.

Perhaps it was in part to remind people not to let the ordered displays in the museum mask the wonderful complexity of the living environment that, in 1995, the museum set up a wildlife garden in the south-west corner of the grounds. From it you get a view of the new building through the trees. At the moment the sheep that are called in once a year to crop a little meadow are in residence. The undergrowth is in a state of faded, autumnal disorder. It is a good antidote to the clinical splendour of the laboratories over the fence.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

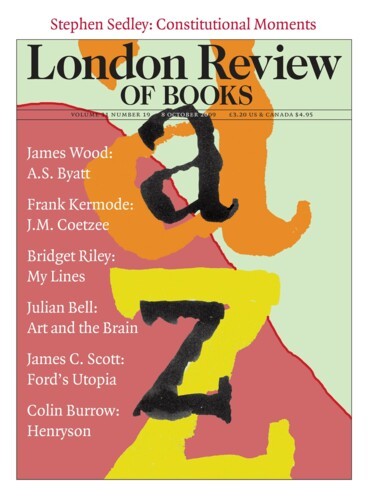

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.