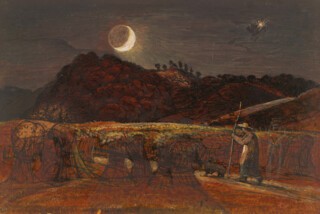

Samuel Palmer had one pocket in his coat for a sketchbook and one for Milton. He recalled the years he was living in Shoreham, the decade from 1825 to 1835, as spent ‘cultivating, among good books, a fastidious and unpopular taste’. During that time he made the pictures for which he is now famous: shepherds and flocks by moonlight, bright clouds, foaming blossom, cornfields heavy with a dream of late summer. None of the Shoreham pictures was shown, sold, or even known to more than a few people in his lifetime (although it’s possible that some of the group of six sepia pen and wash drawings now in the Ashmolean were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1825 – whatever he did show that year was strange enough to have one reviewer suggest that the artist exhibit himself as a curiosity).

An inheritance from his grandfather had made it possible for him to paint how he pleased and what he pleased. When the money ran out he moved from Kent to London, travelled in Britain and Italy, and began to paint more ordinary, saleable, landscapes. Samuel Palmer: Vision and Landscape at the British Museum (until 22 January) shows the range of his work. The peculiar power of the early pictures is reaffirmed and what had become of his talent by the end of his career can be judged. In the suns, moons, bright sunsets, dawns and evenings of some of these later pictures the spiritual light of Shoreham still flickers. In others it is power of observation rather than force of imagination that is striking. In his most beautiful studies from life of buildings and trees, the hallucinatory intensity of his attention to the detail of mossy roofs, leaves and branches is wonderful. There are pen and wash drawings on brown paper which bring to mind Ruskin’s Alpine landscapes. Ruskin praised him only once, but handsomely, in the 1846 edition of the first volume of Modern Painters, where he wrote that Palmer’s ‘studies of foreign foliage especially are beyond all praise for care and fullness’. At the end of his life it was an open commission from Leonard Rowe Valpy, Ruskin’s solicitor, which gave him the freedom to produce a cycle of landscapes based on ‘L’Allegro’ and ‘Il Penseroso’ – paintings cited by those who wish to find proof that his poetic vision hadn’t faded. They are worth attention, but the strangeness which made the Shoreham pictures so striking was not to come again. In a letter to George Richmond in 1834, Palmer wrote:

I believe in my very heart … that all the very finest original pictures and topping things in nature have a certain quaintness by which they partially affect us – not the quaintness of bungling – the queer doing of a common thought – but a curiousness in their beauty – a salt on their tails by which the imagination catches hold on them while the sublime eagles and big birds of the French academy fly up far beyond the sphere of our affections – one of the very deepest sayings I have met with in Lord Bacon seems to me to be ‘There is no excellent beauty without some strangeness in the proportion.’

The strangeness of Palmer’s Shoreham pictures depended on more than freedom from the need to sell. The trajectory of his career stutters and veers like a faulty rocket; what boosted the talent for picture-making he showed when young into something remarkable was contact with other artists. In the compelling self-portrait drawing of around 1824-25, as memorable as any by an English artist, he seems both vulnerable and determined. He was then just out of his teens; a couple of years earlier he had been sought out by an older artist, John Linnell, who had seen and admired his work. Palmer wrote that God had sent Linnell ‘to pluck me from the pit of modernity’. Through Linnell, who was his friend and patron and later his father-in-law, Palmer met William Blake. It was the light of Blake and of the old prints Linnell pointed him towards – in particular those of Dürer, Lucas van Leyden and Bonasone – that showed Palmer the path out of the pit of modernity.

Palmer and his friends, meeting together in Shoreham, called themselves the Ancients. Like the Pre-Raphaelites who came afterwards and the German Nazarenes in Rome who had gone before, they were a brotherhood of artists – the first of the kind in England – who wished to renew art from medieval sources. The Ancients didn’t live communally, as the Nazarenes had done, and, unlike the Pre-Raphaelites, who were supported by Ruskin, had no critical backer. Their work, taken collectively, was not striking in the way that the big, early Pre-Raphaelite oil paintings were, and when financial success came to Linnell through landscapes and to George Richmond through portraits it was by way of pictures which had little or nothing to do with their Ancient status. Not all the Ancients were painters or engravers; it seems that they were as much a society of like-minded aesthetes as a school with a single visual aesthetic. There was no manifesto. In what is recorded of them, mainly in memoirs written years later – stories of night-time walks in the countryside round Shoreham and recitations from Macbeth and The Mysteries of Udolpho – the impression is of a group getting high on ideas rather than serious art workers. William Vaughan notes in the catalogue (it is a model, both comprehensive and enlightening) that Palmer’s son ‘darkly remarked of certain early notebooks by his father’ – he later destroyed them – that ‘they showed “a mental condition which, in many respects is uninviting. It is a condition full of danger, neither sufficiently masculine nor sufficiently reticent.”’*

Five of the six early drawings in the Ashmolean have quotations attached to them, from the Bible, John Lydgate, Milton, Virgil and Shakespeare. But although the pictures are full of objects, they make only glancing reference to these texts. The strange, bare-trunked, big-leafed trees (the kind of thing dinosaurs are shown nibbling in museum panoramas), bright clouds, fields dense with wheat, hills shrubby and woody, all drawn and over-drawn (sepia was mixed with gum arabic) until the paper is as densely inked as a sheet pulled from a heavily etched plate, are informed by a medieval ‘primitivism’ which makes for a ponderousness, a quaint literalness, as though the elisions of the modern mode he was escaping could be compared to mendacity in a verbal description. What the attached quotations affirm is that these are visions of a place far off in time, a world imagined through what has been read as much as constructed from what has been seen.

Turner’s and Constable’s heightened response to weather resulted in sketches of clouds and skies made with near scientific objectivity. They were at it early on, too early for the Ruskinian intuition that a natural order was being destroyed by industrial change to distract them from the facts. Palmer, even in his studies after nature, turns to the literary imagination, looks for the weather of the poets in nature, not finding there the poetry of the painters. His moons cast brighter shadows, his sunsets glow with greater fire than those in the real world.

Retreating from modernity he created a hermetic world, essentially an illustrator’s world. He understood the sources of its attraction. Writing to his patron Valpy about one of the most striking of his late Milton paintings, The Waters Murmuring of around 1880, he says that it will ‘realise golden reflected light in chasmal hollows’, which indeed it does. ‘The moment supposed,’ he says, ‘is that immediately before the poet (in the covert) wakes; when the nymphs sent by the genius of the wood, have just given a staccato tang, preluding the “sweet music” which he is to hear as he awakes.’ The painting, like much good illustration, succeeds by not overspecifying particulars. The figures are small and blurred, the moment described must be understood by, as it were, walking into the picture.

The fashion for that mode of looking was long out of favour when the great revival in Palmer’s reputation began in the 1920s. It is no surprise that it was the Shoreham pictures which were influential and that the later work was seen as a sad decline. Graham Sutherland in his etchings and landscapes, and even Henry Moore, were influenced by him, but it was illustrators such as John Minton who absorbed most from these works, and visionaries of a different sort – Cecil Collins, for example – who were able to go on tapping an analogous vein. Palmer’s gift to posterity was a kind of dream landscape, best seen in the early night scenes. It finds echoes in English romantic painting of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, but closer to it are the slightly spooky depths of rural England evoked by novelists like T.F. Powys, Sylvia Townsend Warner and David Garnett.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.