Oil paint, the most powerful of mediums, can also be nasty-looking stuff. Watercolour can be feeble or messy, tempera can lack verve, distemper can look flat, but none of them has oil paint’s potential for unpleasantness. Its physical qualities – its brilliance, the way impasto can give weight to a brush stroke, the way one colour can merge with another on the canvas, the way it can be spread like butter or, when diluted, dribble down a canvas – are potentially wonderful. Its physicality can, however, get out of hand even in the work of a great painter. When oil paint is put on with a palette knife the picture surface can look like a badly iced cake. There are passages of foliage in Courbet which are nasty in this way; all of Vlaminck demands a strong stomach. It is the quality of the paint – knifed on with forced expressiveness – that makes most of Strindberg’s little pictures in the exhibition at Tate Modern (until 15 May) unpleasant to look at. And they don’t offer much that makes up for the nasty surface. There is usually a band of sea, a band of sky and something rocky or sandy in the foreground. There are cliffs or a lighthouse. In some of them a small, solitary plant is outlined against the sea. The most effective are of breaking waves; some of the least effective are sunsets in which a red disc sinks below the horizon of a putty sea.

They are amateur paintings, but not naive ones. In a handful of pictures from 1873, none much more than 12 inches wide or six inches deep, painted on the island of Kymmendö in the Stockholm Archipelago, there is enough Corot-like attention to the look of things for Strindberg’s feeling for the landscape to register. In Storm after Sunset at Sea, a band of grey clouds seen against a yellow sky, a band of red below them and a dark troubled sea below that, have a Nolde-like intensity. Amateur painting is best when, as in these early pictures, it retains some modesty of aspiration. Pictures from a second burst of activity in the 1890s, in which Strindberg gets his effects by stirring up the paint on the canvas and looks for power in accidental resemblances, try for more and achieve less.

Strindberg was more than distantly aware of the directions art was taking at the turn of the century. He knew Gauguin; a letter from him was printed as an introduction to the catalogue of Gauguin’s 1895 exhibition of Tahitian pictures. In it Strindberg describes how at first he disliked the paintings but then found that he, too, was ‘beginning to feel an immense need to become a savage and create a new world’. He mixed with artists in Paris and Berlin – the most distinguished pictures in this exhibition are portraits of him by Munch. There is another portrait by his friend Carl Larsson, now famous for the pretty pictures he made of his own house and family. Larsson’s paintings give a view of an Arts and Crafts domesticity that is about as far as you can get from Strindberg’s accounts of home life. The friendship didn’t last.

Strindberg challenged norms: in painting and in science as well as in print and on the stage. The intransigence that gave force to his writing made his alchemy foolish – one of the pieces of apparatus he used in his attempts to make gold is on show – and though he took his science seriously, he treated the periodic table as a bourgeois convention. The radical changes in the art of painting which he witnessed from early on – he visited the 1876 Impressionist exhibition in Paris – encouraged artists who believed in their own originality. And Strindberg was original – interested in the place accidents and chance can have in works of art. (He was early in using aleatoric techniques in music, playing songs on a randomly tuned guitar, for instance.) But his inventions didn’t make up for a lack of visual imagination.

His photographs are more interesting. Amateurism – or rather a particular notion of what amateurism is – has come to have a special role and status in photography. The epigraph to the catalogue of the exhibition of the work of André Kertész (at the National Gallery of Art in Washington until 15 May) quotes something he wrote in 1930: ‘I am an amateur and I intend to stay that way for the rest of my life. I reject all forms of professional cleverness or virtuosity … As soon as I have found the image that interests me, I leave it to the lens to record it faithfully.’* Cleverness and virtuosity are, as any photography magazine shows, just what amateurs are encouraged to pursue, but the question of whether the camera can produce images innocent of aesthetic shaping – or, at least, whether the aesthetic act is one of choice rather than of construction – is at the heart of many arguments about photographic aesthetics.

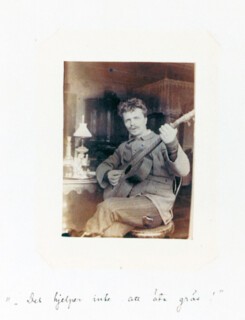

Strindberg played with the idea that the photographic plate offers a direct path to the soul and the universe. He didn’t, of course, do anything as simple as pick up a camera and take pictures. He exposed naked photographic plates to starlight, and called the resulting plates, mottled and speckled with dots, ‘celestographs’. (Never mind that they were the result of accidents in development and nothing to do with stars.) His distrust of intermediaries led him to suspect camera lenses of absorbing the life of the subject, so he made a pinhole camera to be free of them. He planned a survey in words and photographs of rural life in Europe, but exposures and development went wrong and what could have been a milestone in the history of reportage came to nothing. He also made a series of photographic self-portraits which he hoped to publish as a companion to his fourth volume of autobiography. Some of these survive: images of the writer at his desk, with his children, playing the guitar. (They have captions like ‘Come on you old hack, let’s fight,’ and ‘Thank God the damned summer is over. I’d be happy for it to be winter all year.’) They give you a face and an expression – bright, intense eyes; a brisk military moustache turned up at the ends – which fit with the character of a man who would rather fail than conform to anything, even the laws of nature and the facts of optics.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.