Caricature is visible metaphor. Expressed in words, the idea that ‘Napoleon sliced off Europe as France’s share of the global pudding while Pitt took the oceans for Britain,’ is unremarkable. But drawn by Gillray, as The Plumb-pudding in Danger; – or – State Epicures taking un Petit Souper, it comes alive. The two men in absurdly large hats who stab vigorously at the pudding are grotesques. Pitt the Younger, almost skeletally lanky, nose pointed, chin receding, is the type of the aristocratic English silly ass; Napoleon, short, dark, goggle-eyed, that of the greasy wop in some Little England bestiary. But they are much more than stereotypes: each is also a portrait. Gillray’s genius for satiric likeness peoples his stage with human beings, not with the puppets of lesser draughtsmen. Although he could exaggerate grossly – see Burke’s sharp nose and Fox’s blue chin – his knife goes deepest when, exercising his talent for delicately vicious moderation, he does little more than remove the cosmetic smoothing which innate kindness applies to the ugliest face. He emphasises traits of no particular horror so that when his victims are inserted – absurdly or scurrilously – into scenes of disgraceful licentiousness, convincing likeness makes the tar stick. Sometimes they are just straight portraits – and good ones.

This skill with likeness is one thing revealed by James Gillray: The Art of Caricature, at Tate Britain until 2 September – the inclusion of formal portraits of his victims by other hands makes it possible to see exactly how he tweaked appearance. Another is his ability as an engraver. There are passages of wiry drawing in some plates – for example, the figure of Pitt as Death and the white horse which carries him in Presages of the Millennium – which only the most vigorous and controlled pen drawing could match, and which only a master in either medium could achieve. Gillray’s first ambition was to be a reproductive engraver (Richard Godfrey suggests in the catalogue that he failed because he could never avoid exaggerating, if only a little). He possessed a combination of technical abilities which no modern caricaturist can match: a good grasp of anatomy, a fine way with drawn drapery and skill in the management of scenes containing many figures. These, and a flair for straight portraiture, were exceptional talents. Yet we have seen his like, if not his equal, again – the craft still lives. The small section of modern work not only shows that cartooning is one of the rare visual modes in which there is a continuous tradition; it also proves that some modern exponents, stimulated by the unceasing flow of human absurdity, chicanery and mendacity, pack as mean a punch as Gillray. Cartoonists need skills, but unlike painters they have no need to refresh their art by adopting radical styles or new modes of representation (or indeed non-representation). The subject matter waiting every morning to be chopped and shaped keeps the old knives bright. Napoleon, the Prince of Wales and any number of politicians (some of whom, like Canning, eagerly solicited an appearance in his prints) all collected cartoons – and politicians’ offices and lavatories today are decorated with them. The cartoonist is condemned to chastise a class which loves the lash.

Some of Gillray’s plates were little longer in gestation than today’s daily-paper cartoons. Others took more time, however. The exhibition devotes a section to three of these: Shakespeare Sacrificed, Lieut Goverr Gall-Stone and Titianus Redivivus. These large, discursive prints are directed at targets which you now need notes to identify: Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery, a print-publishing venture to which Gillray was not invited to contribute; Philip Thicknesse, an exceptionally unpleasant man, ‘by nature a blackmailer, a lecher, and a sadist’; and the activities of Ann Jemima Provis, a confidence trickster who convinced a large number of Royal Academicians that she had access to a manual which explained the secrets of Titian’s colouring. These are among the most elaborate of Gillray’s prints and the most demanding for modern readers – for read as well as look at them you must.

Altogether, there are many references to absorb. Take the stage shown in Titianus Redivivus. Crowded with painters, it is centred on the distant view of Miss Provis at her easel, her peacock train supported by naked graces. You may well recognise Reynolds in the foreground, rising from the grave with his ear trumpet, but you should also know that Edward Malone, his biographer, said that, were he alive, Reynolds would have subscribed to Miss Provis’s method. The flying, farting putto labelled ‘VENTUS MALONICUS’ now starts to make sense. The portfolios labelled ‘Sandby’, ‘Turner’ and so on, which are being pissed on by a monkey, record the names of painters who weren’t taken in by Miss Provis.

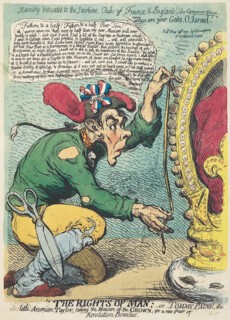

You need to develop a taste for these overcrowded stages, which are wonderfully drawn and thickly inscribed, if you’re not to be cut off from some of Gillray’s highest flights. Gillray clearly loved words, and there are sheets where more space is given to working out the caption than to the visual rough: deny his prints their hybrid nature and concentrate on his visual excellence, and you miss the terrier’s yap and the viper’s hiss. Paine, ‘taking the measure of a crown for a new pair of revolution-breeches’, burbles on anxiously to himself about his old craft of tailoring. Unless you read his speech bubble, the comic anxiety of his face is meaningless.

Gillray could also turn out work which is actually pretty. The Fashionable Mamma – or – The Convenience of Modern Dress shows Mother wearing a fashionable sack dress, with slits in front so that the baby – here being presented to the breast by a nurse whose clothing suggests she has just come up from the country – may feed. Only details – the exposed nipples, the greed of the sucking baby and Mother’s slightly exaggerated Roman nose and long neck – distinguish it from a neatly turned fashion plate. The brilliance and sophistication of The Reception of the Diplomatique and His Suite at the Court of Pekin (Gillray rightly guessing that the trade goods Earl Macartney’s embassy took to China would not impress) makes no concessions to cartoonish distortion.

Coming away from the exhibition I found myself on the train sitting opposite William Pitt. A female William Pitt to be sure, but the nose, mouth and chin were clearly his. It’s a common thing to be left by an exhibition with an after-vision which overlies and colours the world you walk out into – and in this case a disturbing one. The mucky world Gillray invented is not, one finds, a fantasy. It’s one way of seeing things, and once it has taken hold, it is pervasive. Very little is known about his life – there is probably little to know. He lodged with his publisher, Mrs (the title was honorary) Humphrey; he mixed with local tradespeople; he was sought after by politicians and by amateurs. In 1810 he lapsed into insanity, and was cared for by Mrs Humphrey until he died five years later. He troubles us because he was troubled and because, all his working life, he transgressed, putting down on paper an exaggerated view of the way the world is, and one which makes us feel a lot less comfortable.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.