No complete set survives of I Modi, the famous engravings showing positions for copulation, made by Marcantonio from drawings by Giulio Romano: it is said that both copper plates and prints were destroyed by the order of Pope Clement VII. The engraver was imprisoned, and the second edition, which included 16 sonnets written by Pietro Aretino to accompany the pictures, was also supressed. However, there’s a sheet of fragments (with the provocative bits excised) in the British Museum, and drawings made in the mid-19th century by Count Frédéric-Maximilien de Waldeck, based on a set of the engravings found, he said, in a Mexican convent, seem likely to be genuine reconstructions. They conform both with the British Museum fragments and with an edition in which the original engravings have been copied as woodcuts – the illustration here is taken from it – which Lynne Lawner supposes to have been produced in Venice around 1527. The unique surviving copy of this edition was found in 1928 by Walter Toscanini, son of the conductor. The pages of this book, the de Waldeck drawings, the British Museum fragments, and translations of the sonnets, are all included in Lawner’s book. A foreword by George Szabo relates the images of I Modi to the history of erotic art, and traces their use as sources by, for example, majolica-makers.

Lawner’s conclusion is that I Modi ‘proposes an alternative world to the decorous life of the courts; a world outrageous, sinful, heretical, profane and blasphemous, yet humanistic in its heritage’. One aspect of the world of decorum to which the prints and sonnets stood in opposition is examined in Stella Mary Newton’s The Dress of the Venetians 1495-1525, which catches fragments of the exchange between conservative and innovative spirits in the argument of fashion. At the age of 25 a well-born late-15th-century Venetian male put off gay hose, slashed sleeves and padded waistcoats in favour of a veste. This long black gown would be his regular wear for the rest of his life – unless he gained office, in which case he made official appearances in the same garment in red. If he became Doge he was allowed cloth-of-gold. Like present-day university students changing jeans and bomber jackets for business suits, young Venetians gave sartorial expression to corporate solidarity. The sobriety of the Council in times of trouble, and the splendour of representatives of Venice abroad, the licentiousness of the young and the pride of the old, are noted. Dressing well was both civic duty and personal pleasure, regulating it a constant official anxiety. Assessing the evidence is very difficult: not many paintings can be securely dated, and when they can, foreign styles must be distinguished from native ones. But the detail is fascinating. The speed with which changes took place suggests that fashion may have a constant velocity. And animadversions on the dress of the young, on the importation of foreign styles, the extravagance of women and the death of decency, speedily follow change.

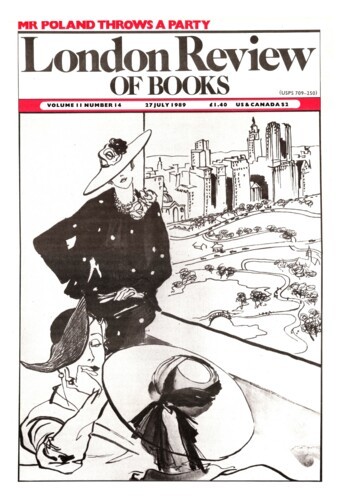

The most recent example of sumptuary law in this country (Second World War rationing) is reflected only distantly in William Packer’s two volumes of Fashion Drawings in Vogue – see this issue’s cover – since the artists were working in the USA for the duration, but in one drawing ‘Eric proposes the latest colours, black and hunter’s green, and “the newest, most prettifying forms of hat – the romantic riding hat”, for the British winter of 1941.’ The drawings are spirited and economical, and, unlike fashion photographs, which tend to excise local detail, frequently comment on the social scene. In one drawing, for example, women arrive for lunch in a smart restaurant; in another, a coloured maid is instructed on what shoes to pack in her mistress’s cabin trunk. While such scenes may have been fantasies for most of Vogue’s readers, they were presented in documentary style – a late flower of the craft of graphic reportage which reached maturity in the work of 19th-century magazine illustrators. (Of Eric – Carl Erickson – it was said that if the model had an ill-fitting dress the drawing would be of just that – a model in an ill-fitting dress.) This way of showing new fashions made sense in a world in which cocktail dresses were still worn to cocktail parties. The ‘where to’ and ‘when to’, as well as the ‘what to’ were acknowledged.

In the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties the presentation of self through clothes, and thus the presentation of fashion, changed. The magazines used more photographs, and those drew on personal fantasies more often than on social ones. Where you were going no longer predicted what you would go in. Plotting the transformations of the feminine and the female in modern fashion, Caroline Evans and Minna Thornton use photographs which turn subtexts into headlines. The iconography of androgyny, neurosis or sexual aggression puts darts, tucks and gussets into the background; the little fictions of the fashion feature which, in the Forties and Fifties, brought to mind a scene from a novel by Elizabeth Bowen, or a short story by Somerset Maugham, expanded to include Genet, The Story of O and comic books. Evans and Thornton spend some time analysing the feminist position on femininity, and here the disapproving tones of 15th-century Venetian officials find odd echoes: the Women’s Liberation Movement’s protest against the Miss America contest was an attempt to ‘ “get out” of fashion’: the Venetian Council had much the same aim. The book is at its most interesting when it goes into detail about how changes in fashion affect the way clothes are made and worn: it is particularly good on the contemporary Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo, who has made garments which question the elementary topology of dress (‘the wearer chooses how to put on two similar garments, one over the other, and where to dispose the spare holes’), and yet has been able to influence high-street clothes; and on Madeleine Vionnet, the French designer of the Twenties and Thirties who, like Kawakubo, helped transform, not just fashion, but the idea of the human body which, for most people most of the time, is implied by the clothes covering it.

The book ends with an anthology. It includes a remark from Helen Olcott Bell which should be included in a general challenge issued to those who do not believe salvation can be achieved through small things: ‘To a woman,’ she writes (read ‘man’ as well), ‘the consciousness of being well-dressed’ – read ‘appropriately’ or ‘pleasingly’ or ‘beautifully’ too – ‘gives a sense of tranquillity that religion fails to bestow.’ And for those who believe there is an escape from fashion there is Simone de Beauvoir: ‘A woman who dresses in an outlandish manner lies when she affirms with an air of simplicity that she dresses to suit herself, nothing more. She knows perfectly well that to suit herself is to be outlandish.’

Clothing is a rich source of coded non-verbal discourse. When Muriel Spark’s schoolgirls set their uniform hats at flirtatious or rebellious angles in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, they remind one that prescribed attire need not reduce the volume of information the medium gets across. This is why sumptuary law, which may defeat extravagance, cannot cure the vain or expunge nonconformity. In this matter the experience of the leaders of spartan Communist regimes, where chic variations on battle fatigues or a Chairman Mao jacket quickly develop, parallels that of Venetian officials and Edinburgh headmistresses. The mating and territorial displays of human beings are not unaffected by their plumage. When Mrs Thatcher’s kingfisher blue appears among the massed grey suits of her cabinet no ethologist would doubt which was the dominant creature.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.