Laila Soueif never normalised her son’s incarceration. Through three arrests and three trials she fought for him in the courts, in legal depositions, appeals, marches, protests. Then, on 29 September 2024, she declared a hunger strike. Laila had given ten years of her life to fighting for her son, and now, in what she decided would be the final act of the fight, she put her life on the line.

Ahdaf Soueif

On Monday, 28 October, six small book collectives, including the Palestine Festival of Literature (PalFest), published an open letter signed by a thousand writers (I am one of them) pledging to boycott Israeli cultural institutions that are ‘complicit in violating Palestinian rights’ and have ‘never publicly recognised the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people as enshrined in international law’. This is the boycott that Palestinian civil society began calling for twenty years ago.

The British Museum is one of the world’s few encyclopaedic museums: it tells the story of how civilisation was built; it boasts seven million visitors a year and is committed to free entry; it holds a unique place of authority in the nation’s – perhaps the world’s – consciousness. A few days ago I resigned from its Board of Trustees.

My resignation was not in protest at a single issue; it was a cumulative response to the museum’s immovability on issues of critical concern to the people who should be its core constituency: the young and the less privileged.

Story: ‘Melody’

Ahdaf Soueif, 30 March 1989

The scent of jasmine fills the air. It has been filling the air every night for the last month, I guess. Which is how you know the season is changing in this country. In this country the bougainvillaea blooms against our walls and windows all the year round. The lizards dart out from under the stones and back in again. The mosquitoes buzz outside the netting and the pool-boy can be seen tending the pool every morning from eight to ten. We’re not allowed to use the pool; women, I mean. It’s only for the kids – and the men of course. They can use anything. And they do. Use anything I mean. And I don’t get to smell the jasmine that much either. You can only really smell it at night and I don’t go out at night that much because of Wayne. Not that there’s anywhere to go, you understand. Only shopping or visiting on the compound. But even that I don’t get to do much of. Wayne sleeps at eight. If he doesn’t get his twelve hours he’s a real grouch all of the next day. And he has to wake up at half-past seven every morning to catch the school bus. Now that’s one thing I could never understand: why was that child never sent to school? She just kept her with her all the time. When we first came to this compound six months ago they were the first people I saw. The first residents, that is. You don’t count the maintenance people and the garden-boys. We moved in on a Friday afternoon and the first thing we did was go right out again and drive up and down the road and I remember we said how convenient to have a grocer’s, a newsagent, a flower-shop and a hospital right on our doorstep practically. Not that any of them looked like they were up to much but still they’d have to be better than nothing. And on the Saturday morning, as Wayne and I came back from the grocery store (Rich had gone to work, of course – that’s my husband) we saw a woman and child standing by the pool. The woman smiled, and Wayne ran over. I followed. Mind you, I thought she looked a bit tacky from the start. Her hair was a dark bronze, obviously dyed, and you could see the roots where it was growing out. She had quite a bit of eye makeup on and her skirt was shorter than you normally see around here. She hadn’t even bothered with an abaya which is normally OK on a compound but not with such a short skirt. The kid was very pretty though and little Wayne fell for her straight away. She was a true blonde with fabulous natural curls. Her face was heart-shaped with a small retroussé nose and big blue eyes and she had drawn one of her mother’s veils over her like a miniature abaya. It turned out she was only a couple of months older than Wayne. But she was much more self-conscious, self-possessed. Being a girl, I guess. Girls grow up quicker than boys. Well, Ingie, that was her name, the woman’s I mean, chatted away – although you couldn’t really call it chatting since her English is appalling – but she told me a bit about the compound and I asked where her kid went to school because I had to decide on a school for Waynie and she said Melody didn’t go to school. She said she had another baby, Murat, who was asleep upstairs just then, and she was keeping them together and teaching Melody at home how to read and write. I thought straight away that that was wrong, although, of course, it wasn’t for me to say, but the kid couldn’t speak a word of English. I mean she was very pretty and everything and in point of fact Wayne was standing there just staring at her all through our conversation. He was smitten. I think he just fell in love. Well, later that day when Wayne dropped his gun into the pool and I couldn’t reach it and he’s crying his head off, Ingie appears at her window and lowers a broomstick, yelling: ‘Try this, try this.’ So we got the gun out of the water and went upstairs to give her back her broomstick and Wayne just would not leave; he had to stay and play with Melody. I’ve never understood what the attraction was, quite frankly. She never played his kind of game. All she’d do was play with dolls and dress and undress them and talk to them – in Turkish. While he watched. And once I went to collect him and found them both sitting around a tub of water on the bathroom floor with bare feet and wet clothes, ‘washing’ all the dolls clothes. And Ingie just laughs and says: ‘It is so hot.’ Ingie’s main thing is laughing. Laughing and clothes and makeup and dancing. And cooking. When we first moved in, she would come round, maybe twice a week, each time with some ‘little thing’ she had made: pastry, apple tart, pizza, whatever. All of them things that take a lot of making. And little Melody was helping her. She also helped her, she said, make all those tiny doll’s clothes for Barbie. I said, ‘But you can buy them at Toyland for nothing,’ and she laughed and shrugged and said: ‘But I like.’ And I guess she likes cooking three-course meals and a dessert for her husband every night and waiting on him too, no doubt. The way these Moslem women treat their husbands just makes me ill. They actually want to be slaves. Mind you, of course, that’s probably how she got him in the first place. I thought it was bit odd when I saw him: a great, big, tall man and obviously a lot older than her. In his fifties maybe. And, laughing, she tells me that they (Ingie, Melody and Murat) are his second family. I pretend to be surprised but in point of fact Elaine had already told me (Elaine is my Scots friend – she’s been here for almost four years and she knows everything), Elaine had told me he used to be married to an American woman and he’d lived in Denver for twenty years. They had two boys and he looked after them and did everything else as well. The wife worked and she had like a strong personality and naturally she wouldn’t do anything in the house. I have a lot of sympathy with that. I mean Housework and me are not the best of friends. I’d rather read a book. I do it here though. Housework, I mean. Since I’m not working and Rich is. But I don’t like it. Anyway. Ingie’s husband (he wasn’t her husband yet at that point of course) he had enough one day so he packed up and went home and got himself a young Turkish wife who would do absolutely everything for him and then he brought her to this country where he could virtually lock her up while he made loads of money. We don’t even know if he ever divorced his first wife. Ingie didn’t say any of this of course. Just said he was a genius and loved his work and could fix any machine in the world and that his first wife ‘is a very bad girl’ and that he is ‘very happy, very joyful man’. And indeed, their Betamaxes are there to prove it. Him dancing in front of friends and family at Melody’s third birthday. A film of him filming Melody and a pregnant Ingie romping in the woods on a holiday in Vermont. All very joyful. Ingie too is ‘very joyful person’. When you visit her she always has some tape on – loud. Disco, rock, Oriental music, whatever. And one of Melody’s favourite games is to sit Wayne down, get her mother to put on some of that wailing, banging stuff, grab a scarf and start dancing for him. And she can dance. Arms and legs twirling. Neck side to side. Leaning backwards. The lot. And Wayne, who normally can’t sit still for a minute, sits transfixed, watching this little blonde who cannot speak a word that means anything to him strutting and flirting about with a veil. I wasn’t even sure this friendship was particularly good for him. But the tears and the tantrums that we had if I tried to stop him from going over – it was just easier to let him go. Once she was supposed to be coming to our apartment to play with him and she didn’t show. He just sat and waited. He wasn’t even four yet but he waited for her for over two hours and then he made me take him over to their apartment and when they weren’t there he sat down on the doorstep and wept. This whole compound, as far as he was concerned, was ‘where Melody lives’. Melody didn’t care as much as he did, I think. But then she had a little brother and Waynie has no one. Well, he has three brothers but they are much older and they’re back in Vancouver. In point of fact we, too, are a second family. Rich was married for fifteen years. I don’t really know that much about his first wife – except he pays her a lot of alimony which is part of the reason why we’re here. But he had three sons and he never wanted to have Wayne. Wayne was the result of a deal I made with Rich. When he got the offer of this job and he really wanted to take it, I said: ‘OK. You give me what I want and you can have what you want.’ I mean, not every woman would agree to be buried alive in a place like this, would she? So he signed the contract and we bought the jeep and set off overland and while we were crossing France I got myself pregnant. He made some jokes about making sure it was a girl, but after Wayne came he really chickened out and went and got himself a vasectomy so I couldn’t nag him for another kid. Ingie said her husband was waiting for their third. Always talking about it. But Elaine said Ingie had told her she was on the Pill. She didn’t want to get pregnant because some fortune-teller back home had said that she would have three children and one would break her heart. So she figured if she only had two, that would somehow invalidate the whole prophecy. I don’t know about all that. I mean, I don’t believe in fortune-tellers myself but sometimes you hear stories of things they’ve said. Well, anyway, Ingie’s husband was on at her to have a third and every month he waited to see if she had conceived and meanwhile she’s secretly on the Pill and hiding the strip among Melody’s pants and vests and terrified that he should find out. That’s what these Moslem men are like: they can never have enough children. Mostly though, they want boys. But this one wanted another girl. I asked Ingie how come he wanted a girl and she said he thought girls were more ‘tender and loving’ than boys. Besides, a boy would always end up ‘belonging’ to his wife while a girl was: ‘her father’s daughter forever. But,’ she added, ‘of course we believe everything that God bring is good.’ Of course.’

Doing something

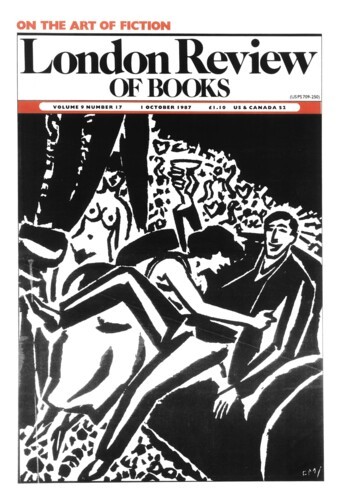

Ahdaf Soueif, 1 October 1987

Three or four years ago, a friend of mine was asked to illustrate a Teaching English book for the Ministry of Education in Cairo. He was (is) an Egyptian, but an Egyptian from outside officialdom – a cartoonist. He painted a series of charming and instantly recognisable street scenes: stacked green-grocers’, lemonade vendors, decked-out taxicabs, dust-carts pulled by donkeys. The Under-Secretary flew into a rage: Who is this man? An Israeli? Why has he drawn everybody with kinky hair? Doesn’t he know selling lemonade on the street is unhygienic? And where did he get all these donkeys? There are no donkeys in Cairo. We want representations of the real Egypt. Eventually the commission went to an artist who had apparently suffered a time-seizure somewhere in Hampshire in the mid-Fifties and the Ministry got its real Egyptians: blazered schoolboys with satchels and freckles and cute, short-dressed little girls with blond pony-tails.’

Podcasts & Videos

Mina's Banner

Ahdaf Soueif

In the 2012 Edward Said Lecture, Ahdaf Soueif tells the story of ‘Mina’s Banner’and the Egyptian revolution.

Pieces about Ahdaf Soueif in the LRB

Forbidden to Grow up: Ahdaf Soueif

Gabriele Annan, 15 July 1999

When Tolstoy died in November 1910, one of the principal characters in Ahdaf Soueif’s new novel felt bereaved: ‘I have derived more enjoyment from Anna Karenina and War and...

Asyah and Saif

Frank Kermode, 25 June 1992

This remarkable novel labours under what some might think serious disadvantages. First of all, at around four hundred thousand words it could be thought on the long side for a book principally...

Edward Said writes about a new literature of the Arab world

Edward Said, 7 July 1983

In this small-scale and intimate first collection of stories by Ahdaf Soueif there is a remarkably productive, somewhat depressing tension between the anecdotal surface of modern, Westernised...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.