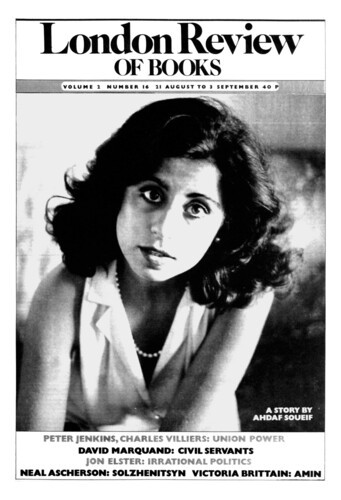

Zeina sat on the bed in her room on the roof staring out of the window. The sun had set, but there was still some light left in the pale blue sky. Clouds were gathering, and she could see the clothes hanging out to dry on the neighbours’ rooftop blowing in the rising wind. It was time to call Sa’d in from the street and give him his supper. She sighed. What bent luck, Zeina, she thought. Young and full of youth and pretty with eyelashes black as night even without kohl and a face fair and full of light and hair smooth as silk. What thighs. What legs. The men are always looking at them as you walk down the street, your melaya draped tightly round your body but showing one full straight leg with a dimpled ankle adorned by a thick silver anklet. Like that boy, what’s his name, the greengrocer’s apprentice ogling you till you had to chide him. ‘What’s wrong with you, boy? You’ve never seen a woman before?’ And he said – curse his cheek – he said: ‘I’ve seen women, Set Om Sa’d, but by the life of Seedna Mohammad, the Prophet, I’ve never seen one with legs like yours.’ A crazy boy. Of course you told him off, pulling your melaya across your face to hide your smile. ‘Shut up, boy. You must be mad or something’s gone wrong with your head. Don’t you know what my husband would do to you if he heard what you said? Haven’t you heard that his anger is worse than that of Iblis, the Devil?’

Zeina sat on the bed in her room on the roof staring out of the window. The sun had set, but there was still some light left in the pale blue sky. Clouds were gathering, and she could see the...