The story of Paula Modersohn-Becker is, according to Diane Radycki, ‘the missing piece in the history of 20th-century modernism’. This is a large claim, and the basis for it is Modersohn-Becker’s series of nude self-portraits, the first such works by a woman. Paula Becker grew up in Dresden until she was 12, when her family moved to the smaller, wealthy city of Bremen, where her father worked as a building and works inspector on the newly nationalised railway. Despite her father’s continual criticism of her ambitions (‘I don’t believe you will be a divinely inspired artist of the first rank’), when she was 16, in 1892, she was allowed to go to London, probably to St John’s Wood School of Art, for two months, and then to Berlin for two years, where she studied at the Association of Women Artists, concentrating on figure portraits and the nude. Back in Bremen during the vacations, she began visiting the artists’ colony at Worpswede, where she moved in September 1898 to study with Fritz Mackensen, who had cofounded the colony with Otto Modersohn.

Worpswede, 16 miles from Bremen, was a hamlet of thatched cottages surrounded by peat bogs. In 1884, Mimi Stolte, whose family owned a shop in the village, met Mackensen while staying with her aunt in Düsseldorf and invited him to spend the holidays in Worpswede. Mackensen and Modersohn decided to settle there in an attempt to set up a community far removed from the rigid academicism of the art school in Düsseldorf which they had both attended. The Worpswede artists shared a love of outdoor painting and liked making life-size works. They painted peasant dwellings with thatched roofs, and boats with black tarred sails slowly carrying peat down the canals. Becker wrote breathlessly in her journal in the late summer of 1897: ‘Worpswede, Worpswede, you are always in my thoughts! … Birches, birches, pine trees and old willows. Beautiful brown moors – exquisite brown! The canals with their black reflections, black as asphalt. The Hamme, with its dark sails – a wonderland, a land of the gods … The atmosphere pervades me to my smallest fingertip.’ The artists exhibited together, published pamphlets and assembled frequently in the Barkenhoff, the house among the birches belonging to Heinrich Vogeler (another former Düsseldorf student) and his wife and former model, Martha Schröder.

Another young female artist who visited the village was my grandmother Margaret Walthour Lippitt. She had attended the Académie Julian in Paris in 1898, a few years before Becker went there. (One day, Sargent came up behind her when she was sketching in the Louvre and remarked on her auburn hair: ‘So like a Titian.’ She was not displeased.) In 1904, she went with her husband to live in Bremen (he was in charge of the cotton exchange there) and over the next ten years made frequent trips to Worpswede. She was especially close to Modersohn and to Rilke, neither of whose names made much impression on me as a child. We had a copy of Modersohn-Becker’s Goose Girl on the stairs, and the deep greens and browns of the northern moors perfectly matched the depressing folk tales my mother had been told when she was growing up in Bremen, and passed on to her own children.

Rilke had been invited to Worpswede in 1898 by Vogeler; he returned often and in 1903 wrote a book about the artists and their use of the local landscape. Modersohn felt belittled by Rilke’s description of him as an illustrator of fairy tales. His landscapes capture perfectly the strange silence of the grasses and trees and pools, and Becker admired them for their rendering of ‘the hot, brooding autumn sun, or the mysterious, sweet evening’. Rilke didn’t mention Becker’s paintings – she hadn’t done her most important work at the time he was writing, and after her death he said she had never shown him her pictures. His judgment of the artists was not generous: he saw them as thrusting the peasants of the village, ‘who are not of their kind, into the landscape’.

There seems to have been a certain amount of posturing, as Modersohn called it, in the artistic community. My grandmother told me that on Sundays at Vogeler’s house all the women would put on their best white dresses, and Vogeler himself – always a dandy – would dress up in a frockcoat and beret. (Vogeler joined the Communist Party after the First World War, emigrated to the Soviet Union and was deported to Kazakhstan, where he died in 1942.)

There could scarcely be any greater contrast than that between the bucolic quiet of Worpswede and the excitement of Paris, where Becker spent the first six months of 1900. Paris was far more open to art education for women than anywhere in Germany, particularly in regard to anatomy and painting from the nude. Becker had read the journals of Marie Bashkirtseff, a young Russian who had studied painting at the Académie Julian in the early 1880s, and was influenced by her enthusiasm.

Becker couldn’t afford the Académie Julian and had to make great efforts to live within her budget: she didn’t heat her room, ate only one meal a day (lunch), and drank barley coffee in the evening. The sculptor Clara Westhoff, whom Becker had met in Worpswede, joined her in Paris, and they each had a small studio on the rue Campagne-Première, near the Académie Colarossi, where they studied for six months, painting from the figure and the nude. Becker wrote to Modersohn, trying to persuade him to come to Paris. He arrived in early June but three days later she received a telegram saying that Modersohn’s wife, Helen, had died. He rushed back to Worpswede, and Becker followed him. They were engaged three months later. Modersohn’s journal records the event: ‘Wed. 12 Sept. Afternoon boating – Paula Becker – Rilke. 5.30 p.m. engaged.’ They married in May 1901, a month after Clara Westhoff married Rilke.

Modersohn-Becker found it hard to get used to her new life in the peace of Worpswede, with a husband and small stepdaughter. On 30 March 1902, she wrote in her journal:

My experience is that marriage doesn’t make you happier. It takes away the wholehearted illusion you previously had of some kindred soul being out there. In marriage, you feel doubly misunderstood because all your previous life was about finding someone who understands … I’m writing this in my kitchen housekeeping book, on Easter Sunday 1902, sitting in my kitchen and cooking roast veal.

As well as finding marriage and rural life difficult, Modersohn-Becker had been upset by the effect of Westhoff’s marriage on their friendship. After their daughter was born, Rilke made it clear that family took precedence over friendship. He wrote to Modersohn-Becker on 12 February 1902:

If your love has remained alert, then it has had to see that the experiences that came to Clara Westhoff hold their value precisely because they have bound themselves closely and indissolubly with the interior of the house where the future is to find us: we had to burn all the wood in our own hearth in order just to warm up our house and make it habitable … Are you surprised that the centres of gravity have shifted, and is your love and friendship so mistrustful that it constantly wants to see and seize on what it owns? You must constantly experience disappointment if you expect to find the old relationship unchanged.

In 1903, she returned to Paris, continuing classes at the Académie Colarossi so that she could paint from the nude, and spending her mornings drawing in the Louvre. Her husband stayed in Worpswede. Radycki says ‘he feared the influence of Paris on his work.’ She was back again in 1905, studying this time at the Académie Julian. Clara Rilke-Westhoff, who was studying at the Institut Rodin, introduced her to Rodin’s work, and she introduced Clara to the work of Gauguin and Cézanne.

Early in 1906 Modersohn-Becker decided to leave her husband for good. Rilke-Westhoff told her own husband that Modersohn-Becker ‘lived unmarried, really, that her husband, beside whom she lives, was not able to perform sexual intercourse because of his nerves … She believes herself able to bear children – and would still like to – when she is alone.’ She left Worpswede ‘without a word’, according to Radycki, in the middle of the night, and took the train to Paris, where Rilke met her at the Gare du Nord. Having settled in Paris, she started painting the female nudes, several of them self-portraits, that would become her most lasting works. ‘I believe I have achieved something good,’ she wrote to her mother in May. But by the end of September she had agreed to return to her husband. It’s not exactly clear why: she couldn’t support herself financially; she was having problems with her work; she felt vulnerable on her own; and her husband had, presumably, promised he would consummate the marriage. ‘I shall be returning to my previous life with certain changes,’ she told Rilke-Westhoff.

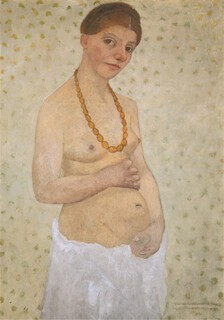

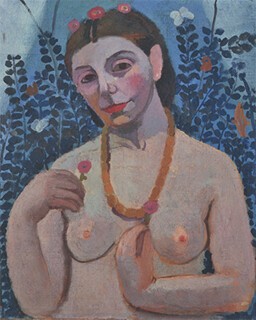

Modersohn-Becker’s portraits and, above all, her self-portraits, nude and clothed, make a forceful statement about female subjectivity. Their singularity and awkwardness testify, as Radycki says, to their newness and ‘outrageous ambition’. Self-Portrait Nude with Amber Necklace, Half-Length II, of 1906, is a joyous affirmation. The thirty-year-old artist looks straight at the viewer. The amber beads, which appear for the first time in her work of this year, hang heavy, and there are flowers, some bedecking her hair, one held in each hand, and some on the foliage behind.

In the most celebrated of these nudes, Self-Portrait on Her Sixth Wedding Day, she wears the beads, has a pregnant-seeming tummy and looks at us sideways. The picture has the label: ‘I painted this at age 30 on my sixth wedding day. P.B.’ This is the only work that she signed and titled, and it celebrates her wedding anniversary in a strange way: when she painted it she thought her marriage was over, and she was not pregnant. Perhaps it was a signal that she wanted to have a baby or perhaps it was simply a demonstration of the fertility of the painter: she often wavered about having a child, and never about her art. She signed herself not ‘PMB’, for Paula Modersohn-Becker, but ‘PB’, ignoring her married name.

Those amber beads have always fascinated me. They are present again in Self-Portrait with Lemon, where the yellow of the fruit sets off the colour of the beads. In her nude and semi-nude pictures they weigh on the body and on the sight and remind me of Suzanne Valadon’s Self-Portrait with Bare Breasts (1931), in which the painter is also wearing beads and at 66 years old calling attention to her ageing breasts. Like Modersohn-Becker, Valadon looks directly out of the picture. The Large Standing Self-Portrait Nude of 1906, in which Modersohn-Becker again holds pieces of fruit, reminds Radycki of Rilke’s ‘Requiem for a Friend’, written a year after her death (which I quote in Burton Pike’s version):

And in the end you saw yourself as a fruit,

you stepped out of your clothes and brought

yourself to the mirror and let yourself

into it, all but your gaze, which remained outside,

immense. And it did not say:

this is me; no, that is.

Early in 1907 Modersohn-Becker got pregnant and painted what Radycki claims is the first self-portrait by a pregnant woman in the history of art. In it she is dressed, isn’t wearing the amber beads, but is holding up two flowers, interpreted here as ‘the creative woman’s twin gifts: her genius and her biology’. She died on 20 November 1907 as the result of an embolism, 18 days after the birth of her daughter, Mathilde.

Modersohn-Becker’s journals were published after her death and became ‘enormously popular’. Rilke thought they misrepresented her. He refused Modersohn-Becker’s mother’s request that he edit them, saying that they wouldn’t do the artist’s reputation any good. He felt that they ‘distract one from her work … For where do they let us learn that this accommodating creature, who met the demands of family communication so compliantly and co-operatively, would, later, be seized by the passion of her task, renouncing all else, shoulder loneliness and poverty.’ It’s clear, however, why many have loved the journals: they are full of warm and telling descriptions of her surroundings, her daily life, her moods, her ambitions for her painting, the joy she took in the thick application of paint, or her excitement over glazing techniques. For Rilke, though, ‘the Paula Modersohn to which they contribute would inevitably be indescribably inferior to her freedom, to the one she ultimately attained in her final year and in the great beauty of her departure from us.’ But he saw the heavy amber beads and her pregnancy as a ‘bad omen’:

what do you mean by the contour of your belly

laid out like the lines of a palm

so that I can no longer read it but as destiny?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.