In 1920, Samuel Rosenstock, better known as the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara, one of the founders of the Dada movement, which wanted to remake the world as an experientially liberating place where meanings could be freely rewritten, asked fifty artists from ten countries to contribute work that could be published in an anthology to be entitled Dadaglobe. Dada had begun in 1916 in the performances and readings put on by its members at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich, which were intended to express disgust with the First World War and the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist policies that led to it. Tzara desperately wanted to escape too the narrow nationalism and individualism (Dada opposed any idea of leadership) characteristic of the postwar period. The political world was demanding the use of passports and identity papers while Dada protested in the name of the collective: by 1920, the movement had spread to Berlin, Hanover, Cologne, Paris and New York, and there were ‘présidents et présidentes de Dada’ from eight countries and three continents.

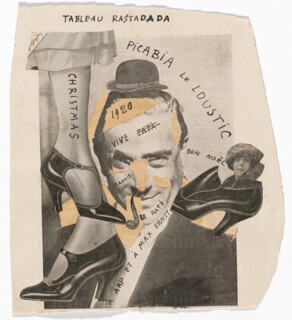

The anthology was never printed because the painter Francis Picabia, who had said he would pay for it, fell out with Tzara. Dadaglobe Reconstructed, first shown in Zürich and now at MoMA in New York (until 18 September) displays the contributions Tzara received. There were four signatories – Picabia, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Tzara and Walter (signed ‘Dr’) Serner – to the letters written on smart notepaper headed ‘Le Mouvement, Dada’, all requesting contributions for an anthology intended to emphasise ‘the collaboration, in all languages, of Dadaists of the whole world’. It was to be published by La Sirène in Paris, with a print run of ten thousand. The artists were asked to send two or three reproductions of artworks, drawings, designs for book pages or a photograph of themselves, altered as desired, as well as literary texts. The contributions poured in.

There was a precedent: Richard Huelsenbeck had intended to publish a similar collection called Dadaco early in 1920. Some trial pages were printed but the project seems to have been abandoned on grounds of cost. The volume was first intended to be entitled Dadako, a term combining art with enterprise, but as a result of Tzara’s antipathy to the letter ‘K’ (think Amerika) it was changed. (As for changes, Huelsenbeck moved to New York, where he became Charles R. Hulbeck, psychoanalyst.) The use of the portmanteau word ‘Dadaco’ is reminiscent of Kurt Schwitters’s use of the second syllable of ‘Kommerz’ in his Merzbilder, works created from things he found in the streets: ‘Everything was ruined,’ he wrote, ‘and it was a matter of building new things from debris.’ The syllable ‘merz’ was cut out from an ad for a bank.

Tzara said he hoped to receive ‘aesthetic essays that read like manifestos … that is to say: steadfast, neat, final and ardent’. It’s hard to think of his own Dada manifestos as ‘neat’, however final he might have wanted them to sound, though they were ardent. ‘I say,’ he declared in 1918, ‘there is no beginning and we are not trembling, we are not sentimental. We shred the linen of clouds and prayer like a furious wind, preparing the great spectacle of disaster, fire, decomposition.’ As Adrian Sudhalter, the co-curator of this show, puts it: ‘The idea of an international Dada anthology for which contributions might travel through the mail as surrogates, in effect, for individuals forbidden to do so in that epoch, registered as not only relevant, but urgent.’ Tzara himself didn’t manage to travel to Paris until January 1920; it was even more difficult for the movement’s German supporters. But Dada believed that the movement could spread, whatever the constraints on its individual members, and Dadaglobe was intended to show this.

The exhibition is split into four sections representing the different possibilities stipulated in the letter. The self-portraits are hung with texts in the glass cases below corresponding to the faces above. Man Ray sent two texts, ‘L’Inquiétude’ and the unintelligible ‘Simultaneous Dialogue’. One of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s wooden constructions is included; in the photograph she sent she is half-hidden by its wooden head. Further along, Jean Crotti’s intriguing geometric forms are far too seldom seen, as are those of his wife, Suzanne Crotti, sister of Marcel Duchamp, whose gouache, Usine de mes pensées, seems to represent the factory of her thoughts, with the rectangular blocks of buildings set astride parallel railroad tracks. You could look at her infinitely complicated Broken and Restored Multiplication for over an hour. Everything here feels both wedged in and spacious. In the last room, it’s a joy to see Ribemont-Dessaignes putting God so delicately on a bicycle. Duchamp himself sent a photo reproduction of To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour and his Bride, both shown here along with the originals.

Many of the works here are early versions of later and more famous pieces: Max Ernst’s collage The Chinese Nightingale, with the hands uplifted to the single eye underneath the fan, makes us think of the raised arm in his Celebes of 1921 in the Tate, and of the threatening bird-headed creatures in Oedipus Rex of 1922. Anton Bragaglia’s Portrait of Julius Evola, in which Evola’s left eye is encircled by a dark circle with a diagonal stripe slipping down his cheek, is no less visually suggestive, and reminds us of the monocle worn by Tzara.

It might be supposed that the parodic portrait by Man Ray of L’Homme as an eggbeater, stirring up this and that, responds to La Femme with its uninterpretable protrusions and bowling-ball shapes. According to the catalogue for the show, this may have been originally intended as a double portrait of Man Ray (‘Man’) and Duchamp; Man apparently switched the titles on the second set of prints, which he later sent to Jean Arp. It’s easy to love the visual and language play here: the photo of Tzara with ‘DADA’ written over his forehead; the photo of Raoul Hausmann with ‘section de merde allemande’ neatly printed on his face.

Some groupings are particularly engaging, like the triple gatherings of the photomontages by Ernst: his collage portraits of his wife, Armada v. Duldgedalzen, la Rosa Bonheur des Dadas, and his son, Jimmy, Dadafex minimus, le plus grand antiphilosophe du monde, the title referring to Tzara’s manifesto ‘Monsieur AA the Antiphilosophe’, are shown along with Ernst’s own Fatagaga, as these collages, done in collaboration with Jean Arp, were known (it’s short for ‘Fabrication de tableaux garantis gazométriques’). In The Punching Ball ou l’Immortalité de Buonarroti of 1920 Ernst has ‘dadamax’ written across his cheek and holds a bust of Buonarroti. The Fatagaga of a very altered double photo of Ernst and Arp, with Arp looking down and Ernst looking at us, is also included here.

We still don’t know why Picabia stopped his funding of Dadaglobe and what the falling-out with Tzara was really about. But it’s wonderful finally to see the works they collected together in the same place, demonstrating that the spirit and energy of Dada is still evident now, a century on, together with the social ills that brought about its birth.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.