One late January afternoon in 1979, before taking the night train from Paris to Barcelona, I had tea with Jacqueline Lamba in her studio apartment on the fifth floor of 8 boulevard Bonne Nouvelle. I climbed the many steps more slowly than Jacqueline, who bounded up in her long skirt (like those of her friend Frida Kahlo). She was a painter, and ‘scandalously beautiful’, according to André Breton, who had married her and written L’Amour fou for her in 1937.

I first met her in August 1973 in Simiane-la-Rotonde, a hilltop town in the Vaucluse, not very far from the cabanon, a small stone house in a field, where I spend my summers in France. For several hours we talked about Breton and Artaud, and Surrealism as she had known it. One day she came to the cabanon and, in the noontime blaze, insisted on walking up the nearby hill to the chapel of Notre-Dame-des-Anges, leading my children by the hand. On another summer evening, we drove her home to Simiane late at night, and an owl accompanied our yellow car, a 2CV with its canvas roof rolled back, all the way, like some sort of sign. For me, she was only good fortune. ‘Ah,’ she would say, ‘if that publisher won’t take your essays, I shall go there and hurl all his manuscripts to the floor.’ A sketch of Simiane that she gave us still hangs in our cabanon.

Over those years, Jacqueline and I talked about many subjects, from poetry to psychoanalysis. We would talk for so long that the chimney in her little studio with its white walls would go cold: ‘I had let the fire go out without noticing, then I lit it again to bring you back,’ she wrote to me after one of those evenings. When I translated Breton’s L’Amourfou, I found her reminiscences wonderfully helpful, particularly about René Char, who lived nearby at L’Isle sur la Sorgue.

That January afternoon, before I left for Spain, Jacqueline handed me a small envelope and told me to open it at midnight. I was sharing a sleeping compartment with five Spanish men, and my Spanish wasn’t up to following their conversation even had I wished to do so. I looked at my watch, found it was midnight, and opened the pale grey envelope. It contained one thin page covered with tiny and careful lettering and was addressed in pale green ink to ‘Ondine’, the water nymph. It was dated 7 August 1934. Jacqueline was then earning her living as an unclothed swimmer in the Coliseum, a spectacle Breton enjoyed, inviting his friends to come along in the evenings. This is the letter he sent Jacqueline Lamba:

Ondine et Paradis! Je n’étais pas du tout prêt à me lever lorsqu’on est venu m’apporter la lettre la plus belle de toutes, il fallait absolument que ce fût ainsi. Il faisait encore très sombre, on devinait un de ces ciels blafards qui nous sont donnés depuis que tu es partie, celui d’aujourd’hui bat du reste tous les records et je t’ai vue longuement sans rien voir. Tu étais là te faisant attendre et j’imaginais mille choses plus horribles les unes que les autres; je relisais bien au delà de les savoir par coeur certaines phrases répondant tellement aux désirs que je t’exprimais hier et je me fascinais devant tels mots d’un tissu violet si lâche … Je t’AIME tant ainsi, je sais si peu que nous sommes encore sur la terre. Je voudrais me disperser pour toi dans l’eau, dans le soleil et dans le vent. N’oublie pas que je t’attends ce soir encore, songe demain qu’à onze heures, je me serai mis pour toi à genoux, j’adore cette prière.

… J’ai fait brusquement la rencontre d’un personnage extrêmement particulier. Il s’agit d’un médecin ami de consuls, avec qui j’ai passé dans une assez grande agitation la fin de la soirée d’avant-hier où j’avais dîné chez René Char et toute la soirée d’hier. En un clin d’oeil nous avons eu, lui et moi, l’impression de nous trouver sur des points très spéciaux des affinités extraordinaires, comment dire, de posséder des lueurs complémentaires sur certaines choses très difficiles. C’est un ancien chef de clinique de la faculté de Paris, c’est-à-dire professionellement quelqu’un de tout premier ordre et, de plus, il est extrêmement versé en occultisme. Comme j’avais été tenté de lui parler presque tout de suite de ce qui m’émeut tant dans le passage du fictif au réel marqué par l’accomplissement de ‘Tournesol’, il a réussi à me dire d’emblée sur ce sujet des choses étonnamment impressionnantes (découvrant par exemple que j’avais certainement ‘Jupiter en 9e maison’). Il s’est d’ailleurs passionné littéralement pour cette histoire qu’il m’a supplié de la laisser approfondir avec moi. Je suis tout à fait sûr que la rencontre que cet homme et moi avons fait l’un de l’autre est des plus magnétiques, et il en a manifestement la même conscience que moi. Hier soir il n’avait pas plus tôt promené un regard circulaire sur l’atelier et prononcé quelques mots sur le caractère magique et ‘noir’ de l’assemblage des objets que les lampes se sont éteintes, ce qui s’est plusieurs fois produit dans des circonstances analogues, dont Eluard par exemple peut témoigner, comme Giacometti peut témoigner de notre trouble à tous pendant cette très courte éclipse d’hier.

Mon beau Démon … ceci pour te montrer que je suis toujours dans les bonnes grâces du démon. Mon bel Elément liquide, je m’inonde de toi. Y aura-t-il des landes assez grises, des rochers assez tourmentés, assez brisants, des bois assez creux pour notre vol associé de ce soir? Un seul mot encore, mais qu’il soit du moins porté par ma voix: Je t’aime.

André

Here it is in English:

Ondine and Paradise! I wasn’t at all ready to wake up when they came to bring me the most beautiful letter of all, and that’s just the way it should have been. It was still very dark, you could just see one of those pallid skies we’ve had since you left, today breaking all the records, and I saw you lengthily without seeing anything. You were there, I was waiting for you, and I imagined a thousand things, each more dreadful than the others; I was reading again, already knowing them by heart, certain sentences answering so clearly the desires I expressed to you yesterday and I was fascinated by the appearance of words of such a soft violet cloth … I LOVE YOU so much, I am so unaware that we are still on this earth. I would like to disperse myself for you in the water, in the sun and in the wind. Don’t forget that I’m waiting for you again tonight, think tomorrow that at 11 I shall have knelt for you, I adore this prayer.

… I have just now made the acquaintance of someone very special. He’s a doctor to various consuls, with whom, after dining with René Char, I spent the end of the evening the night before last in a rather exhilarated state and all last evening. In an instant we had, he and I, the impression of sharing some extraordinary affinities on rather unusual points, how can I put it, of possessing complementary views on certain very difficult things. He’s the former head of a clinic in the University of Paris, that is, clearly someone at the top of his profession and he is also extremely learned in occultism. As I was tempted to talk to him almost immediately about what so moves me in the passage of the fictional to the real marked by the events of ‘Sunflower’, he mentioned right then some extremely impressive things about it (discovering for example that I had certainly ‘Jupiter in the ninth house’). He got so excited about this happening that he begged me to allow us to examine it together in greater depth. I am absolutely convinced that our discovery of each other is endowed with the highest magnetism, and he is obviously convinced likewise. In the evening he had no sooner looked around the studio and said a few words about the magic and ‘black’ character of the assembly of objects than the lamps went out, which happened several times in analogous circumstances, about which Eluard can bear witness, as Giacometti can bear witness to our collective disturbance during yesterday’s very short eclipse.

My lovely Demon … this to show you that I am still in the good graces of the demon. My beautiful liquid Element, I drown in you. Will there be heaths grey enough, rocks tormented enough, forests hollow enough for our flight together tonight? One more word, but let it be at least carried by my voice: I love you.

André

Some points in the letter take a bit of explanation, and some are clarified by Breton’s 1923 poem ‘Tournesol’. The water imagery refers, like the name Ondine, to Jacqueline swimming naked in the Coliseum, and ‘Jupiter in the ninth house’ refers to an astrological sign, characterised – for example, on the website Café Astrology – in a way that would have appealed to Breton:

You are always hungry for knowledge and wisdom. You have a naturally philosophical nature, and you enjoy sharing your opinions and knowledge with others. You can be a natural teacher, and you love the learning process. You very strongly value freedom of movement and expression. You can easily be inspirational, and find success in travel, education, teaching, sports, publishing and foreign cultures.

Breton marvelled at the way his poem ‘Tournesol’ predicted his encounter with Jacqueline in the Café de la Place Blanche. She had gone there intending to make his acquaintance, and was writing to him when he saw her. Breton recounts the episode in L’Amour fou, with the repetitions revealing his obsession:

This young woman who just entered appeared to be swathed in mist – clothed in fire? … this woman was scandalously beautiful … This young woman who had just entered was writing – she had also been writing the evening before, and I had already agreeably supposed very quickly that she might have been writing to me, and found myself awaiting her letter …

They take a walk near Les Halles, and doubt sets in: ‘There would still be time to turn back.’ They pass by the Tour Saint-Jacques and he feels

a whole violent existence forming around it to include us, to contain wildness itself in its gallop of cloud about us:

In Paris the Tour Saint-Jacques swaying

Like a sunflower

He quotes his own poem, thinking now that the swaying of the tower represents his own hesitation between the two meanings of the word ‘tournesol’: a sunflower and blue litmus paper. Then he succumbs to a ‘wonderful dizziness’ that leads him ‘fearlessly towards the light! Turn, oh sun, and you, oh great night, banish from my heart everything that is not faith in my new star!’ and quotes the full poem.

Tournesol (1923)

La voyageuse qui traverse Les Halles à la tombée de l’été

Marchait sur la pointe des pieds …

Au Chien qui fume

Où venaient d’entrer le pour et le contre

La jeune femme ne pouvait être vue d’eux que mal et de biais

Avais-je affaire à l’ambassadrice du salpêtre

Ou de la courbe blanche sur fond noir que nous appelons pensée …

La dame sans ombre s’agenouilla sur le Pont-au-Change

Rue Gît-le-Coeur les timbres n’étaient plus les mêmes

Les promesses de nuits étaient enfin tenues

Les pigeons voyageurs les baisers de secours

Se joignaient aux seins de la belle inconnue

Dardés sous le crêpe des significations parfaites

Une ferme prospérait en plein Paris

Et ses fenêtres donnaient sur la voie lactée

Mais personne ne l’habitait encore à cause des survenants

Des survenants qu’on sait plus dévoués que les revenants

Les uns comme cette femme ont l’air de nager

Et dans l’amour il entre un peu de leur substance

Elle les intériorise …Sunflower

The traveller passing through the Halles at summerfall

Was walking on her tiptoes …

At the Smoking Dog café

Where the pro and the con had just come in

The young woman could scarcely be seen by them, and only askance

Was I speaking with the ambassadress of saltpetre

Or of the white curve on black ground we call thought …

The lady with no shadow knelt on the Pont-au-Change

Rue Gît-le-Coeur the stamps were no longer the same

Night-time pledges were kept at last

Homing pigeons helping kisses

Met with the breasts of the lovely stranger

Pointing through the crepe of perfect meanings

A farm prospered in the heart of Paris

And its windows looked out on the Milky Way

But no one lived there yet because of the chance comers

Comers more devoted still, we know, than ghosts

Some of them seem to swim like that woman

And in love there enters a bit of their substance

She interiorises them …

Breton then analyses his poem and, with certain reservations, claims that he believes ‘it is possible to confront the purely imaginary adventure which is framed in the poem and the later realisation – impressive in its rigour – of this adventure in life itself.’ The most minute points now seem to him to prefigure later occurrences. The mention of ‘homing pigeons’, for example, because he has just received a letter with the seal of a dove on it, and – a major prefiguration – the ‘swimming woman’. In L’Amour fou the entire episode of encounter and prefiguration ends: ‘The following 14 August, I married the all-powerful commander of the night of the sunflower.’

This took place about three months after their first meeting. The letter Breton sent Jacqueline on 7 August 1934 was kept inside the original copy of L’Amour fou, in which photographs by Man Ray, Dora Maar and Brassaï are enclosed in a wooden cover made by Georges Hugnet. Jacqueline suggested that the Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet in Paris should buy the book, but it couldn’t afford to pay. She then asked me to sell the original somewhere in the United States for $20,000 and in a letter described some of its pages and sent photos of them. She wrote, as she often did, in inks of several colours, using the colours for varying emphasis. I tried every dealer I could think of, but none offered enough, and the book remained in France. She would have liked to have the original available for others to study, she said, but ‘tant pis … Anyway, dealers are the worst kind of people.’

I have held on to the letter without publishing it or even referring to it. I am grateful to the daughter of Jacqueline Lamba and André Breton, Aube Elléouët, for her permission to publish it now. I am giving it to the Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet as a sort of substitute for the original of L’Amour fou, and in honour of Jacqueline Lamba.

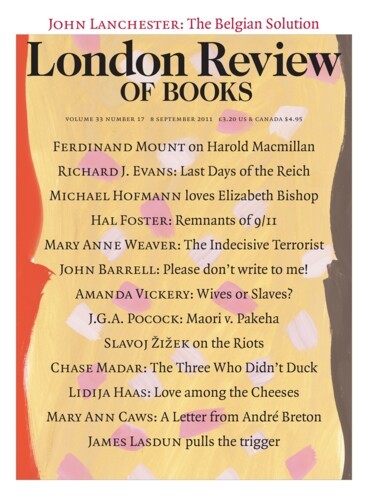

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.