Full recognition came late to Louise Bourgeois. Born in France in 1911, she married the American art historian Robert Goldwater in 1938 and moved to New York, where she worked first as a painter and then, after 1940, mainly as a sculptor and assembler of installations. The catalogue of the exhibition of her work at Tate Modern (until 20 January) consists mainly of handsomely illustrated, alphabetically arranged entries by a number of commentators. The longest take up a few pages, the shortest a few lines. Many draw on her own writings, published and unpublished. As a result the critical generalities which are normally segregated in introductory essays are mixed with the kind of detail usually found in catalogue entries. You can dip or skip, picking up cross-references as you go.

This suggests a way of thinking about Bourgeois’s work, and about museums. In museums of costume, say, or natural history, or cars, one is aware that taking objects out of circulation must diminish them. Clothes can only be fully appreciated on real bodies, animals when alive, cars when in motion. The art museum suffers much less from this kind of alienation. Many pictures were always intended to be seen in galleries. They are as proper a place for them as the theatre is for plays. Religious art may give one pause – even non-believers can feel that an object of veneration, an altarpiece say, loses something when put in a cool well-lit place, but on the whole art stands up to the museum pretty well. For many modern painters the museum was the space they had in mind, an extension of some ideal studio. But Bourgeois, speaking of her ‘cells’ – enclosed spaces like open-topped rooms, furnished and dressed like stage sets – said: ‘I wanted to create my own architecture, and not depend on the museum space, not have to adapt my scale to it.’

The masks and fetishes in ethnographical museums that artists in the early 20th century found so liberating are very unlike the works of modern art that can be traced back to them. Separated from myth-making and ceremony they are as unfulfilled as the unworn frocks and stuffed birds. Bourgeois has mythologised her family history, her life, her anxieties and feelings. Her references to feminism, gender difference, the body and its pains and satisfactions, are personal. Looking at her work in displays like those at the Tate – which separate the mask, as it were, from the ceremony – one feels to a degree excluded from what made her own work important to her. At times you are grateful. Some of the objects would like to enter your imagination by a back door that you might think it better to keep shut. You don’t always want to be spooked. The spirit of her work runs against the gallery’s tendency to tame and contain feeling, to reward masterly confidence. There are pieces here that, found on a forest path, would seem to contain ominous warnings.

Some of what she has made is nasty: turd-like in shape and tacky in texture. Femme Pieu, a small black object, like a heart with a pointed end and a central cleft into which pins are stuck, suggests bad magic. The two-foot-long latex-over-plaster cock and balls called Fillette defeats critical vocabulary. On the one hand, one could describe it as some kind of three-dimensional graffito, on the other, one wants to make sense of what she says of it: ‘Everything I loved had the shape of the people around me – the shape of my husband, the shape of my children. So when I wanted to represent something I loved, I obviously represented a little penis.’ Her statements are sometimes gnomic, but never boringly opaque. Robert Mapplethorpe photographed her with Fillette tucked under her arm like a shotgun. She looks out at him with mischievous amusement. The gloopy surface of Fillette turns out to be no more disturbing than the icing-smooth gloss of a pink marble, multi-breasted, headless dog with phallus. This figure, Nature Study, is identified by Bourgeois as ‘a self-portrait, an animal metamorphosis of the artist’.

This identification is typical. Mother and father, husband and children, childhood and betrayal are the source of the feelings the work builds on. In 1996 she stitched a handkerchief with the words ‘I HAVE BEEN TO HELL AND BACK. AND LET ME TELL YOU, IT WAS WONDERFUL.’ Maman, the giant spider already seen in the Tate’s turbine hall in 2000, protects the sac of marble eggs attached to her abdomen and menaces the viewer. ‘My best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and useful as an araignée,’ Bourgeois wrote. As for fathers, after going through a list of men – doctors (her own and her mother’s), teachers, a foundry owner, savants (Charcot, Lacan, Bateson), artists (Breton, Duchamp) – she said: ‘They are all ridiculous Don Juan macho father figures … they have all motivated my work. I had a bone of contention with each one of them and was out to call their bluff and still am.’

Her own father’s worst betrayal was to have as his mistress for ten years the Englishwoman employed to teach his children. Writing about The Destruction of the Father, an exercise in claustrophobia in which plaster and latex mounds in an open-fronted box – ‘abscesses’, the catalogue calls them – are lit with red light, she said:

This piece is basically a table, the awful, terrifying family dinner table headed by the father who sits and gloats. And the others, the wife, the children, what can they do? They sit there, in silence. The mother, of course, tries to satisfy the tyrant, her husband … So, in exasperation, we grabbed the man, threw him on the table, dismembered him and proceeded to devour him.

The spider mother and the monster father owned and ran a tapestry-repair company. The cannibal daughter worked there too. No account of the sculptor David Smith fails to notice his time as a welder on a production line; Bourgeois’s stitching should be thought of in the same way. A skill already learned, waiting to give a flavour of unusual competence to quite different constructions. When, in Seven in a Bed, she stitches together an orgy of pink, stuffed dolls the workmanlike seams domesticate the subject matter. Early sculptures from the 1940s and 1950s are skinny ‘personages’ – not much more than whittled sticks. Later she threaded bits of wood onto steel rods or packed them into a tall, open-fronted box. In more recent pieces the threaded items are sometimes little pillows of ticking covered in tapestry.

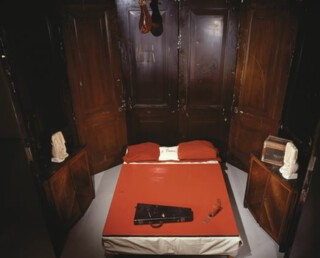

The most explicit invitation to voyeurism comes with the open-topped rooms she calls ‘cells’, like the one shown here. Many are within palisades of old doors or panels and you find yourself peering through a window or round a corner to check out what is laid out on a bed or hung from a hook. The general effect tends towards melancholy. Old clothes, spools of yarn, mirrors and models seem like echoes of Surrealist assemblages, but sometimes an oversized element (a monstrously long man’s coat hanging on a wall, for example), the general oddness of things and the feeling that you might be entering the imagination of a not altogether nice little girl brings Alice in Wonderland to mind. Passage Dangereux, a corridor defined by large wire cages filled with an odd collection of junk, is similarly and dustily disturbing.

Bourgeois at one time or another met, often knew well, the great artists of her time, first in France and later in America. While they pursued single ways of making art – and were told that they stood on the threshold of a future in which Modernism would advance with an assurance to match that of the thousand years of art that lay behind them – Bourgeois was playing Martha in the kitchen, cooking up art that seemed to be the work of a not-quite-in-tune follower of a whole string of them, but which now looks much more contrary. ‘What modern art means,’ Bourgeois has said,

is that you have to keep finding new ways to express yourself, to express the problems, that there are no settled ways, no fixed approach. This is a painful situation, and modern art is about this painful situation of having no absolutely definite way of expressing yourself. This is why modern art will continue, because this condition remains; it is the modern human condition.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.