In the archives of the British Empire and Commonwealth Collection, held in Bristol, you can find a neatly closing polished wooden box, inside which are half a dozen 8 mm film reels, with about fourteen minutes of footage per reel. The films were shot by Air Commodore Leonard de Ville Chisman, DFC CBE (1899-1974). They show something you almost never see: candid images of colonial warfare, shot during military action. On one of the reels, servicemen can be seen preparing for air raids and loading aircraft with bombs; Chisman then takes the camera into the cockpit and films the bombing and machine-gunning of villages from the air. The attack took place in January 1937, and the target was Arsal Kot in Waziristan, which the British were seeking to pacify. But there’s also an earlier sequence, in which an airman (Chisman?) stands in front of his Westland Wapiti, holding up a leaflet for the camera, before affixing large bundles of them, wrapped in fabric, to the plane’s undercarriage. Back in the cockpit, the film shows thousands of leaflets being dropped over the villages that are soon to be bombed: clouds of paper can be seen fluttering down over the rugged landscape surrounding Arsal Kot.

Chisman’s wooden box contains another item: a large piece of fragile, yellowed paper, somewhat larger than A2-sized, slightly tattered at the edges, carefully folded. Clearly, this is one of the leaflets – presumably kept by Chisman as a souvenir. The same text is printed twice in sturdy calligraphic script, first in Pashto, then again in Urdu:

Notice

To the armed militants in the vicinity of Arsal Kot

As you have taken advantage of the cessation of airstrikes to re-enter Arsal Kot and are using it as a base to commit crimes against Government forces, this notification is to inform you that airstrikes will resume on Tuesday, 12 January 1937, and will continue until further notice.

From the afternoon of Tuesday, 12 January, staying within two miles of the above-mentioned area will be dangerous.

Everybody must therefore leave the area and stay out until otherwise informed. The Government does not want your women or children to come to any harm, so take them immediately to any place of safety.

You are also advised that touching any kind of unexploded bomb or artillery shell carries an extreme risk.

By order of the Government

Chisman had joined the Royal Naval Air Service in 1917, and saw action in the Mediterranean theatre; by 1922 he had become an armaments specialist in the RAF, and was eventually transferred to what is now Pakistan but was then British India, where he became commander of the RAF’s Army Co-operation squadrons in Peshawar and the North-West Frontier Province (‘army co-operation’ is now called ‘close air support’ – air back-up for soldiers on the ground). It was for his service in Waziristan that he received his Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded for gallantry between January and September 1937. The bombardment of Arsal Kot was part of a long and ultimately unsuccessful British campaign against Mirza Ali Khan, a charismatic Sufi mystic known in the British press as ‘the Faqir of Ipi’. His insurgency, in which he was backed by the Afghans, would grind on until Partition, causing the British serious problems. Khan has been described as ‘the most determined, implacable single adversary the British Raj in India had to face amongst its own subjects’; he was never captured or killed, and on his death in 1960 the Times described him as a ‘doughty and honourable opponent’.

The squadrons commanded by Chisman were engaged in what was then known as ‘air policing’. The doctrine had been perfected by the British in Iraq in the mid-1920s, though it had earlier been used in Somaliland. It involved using the air force to conduct carefully targeted and destructive bombing raids as a way of maintaining order without the need for ground troops. Leaflet drops intended to communicate British intentions and requests ahead of the raids were used from the very start, and were integral to the practice. The aim was to subdue restive or disobedient colonial subjects in distant, inaccessible or dangerous areas, forcing them to conform to the will of the colonial government without the need for direct occupation (‘control without occupation’).

The classical doctrine centred less on outright killing than on the potentially catastrophic and continuous disruption of daily life, through the destruction of civilian dwellings, farmland and livestock. But the value of violent mayhem was well understood and planes were often deliberately used to inflict heavy casualties. (This was particularly true against the Nuer of Southern Sudan, who were regularly bombed and machine-gunned from the air.) Leaflet drops informed people that because of the actions their leaders had taken, or because there were insurgents hiding among them, they should immediately leave a proscribed area. Continuous air strikes then prevented people from returning until the government’s demands were met, effectively blockading them from their own homes and livelihoods. Casualties were viewed as the responsibility of the victims, who were considered to have been amply warned. (‘Those who have been hurt have disobeyed and their deaths are their own fault,’ as a leaflet dropped over the hinterland of Aden put it.) The bombing could be ferocious, with thousands of munitions delivered in air raids that could last up to eighteen hours a day for weeks on end. It was considered a generally successful and cost-effective policy, and in the interwar years the RAF became the favoured instrument of colonial control across swathes of the British Empire, from Sudan to India via Palestine and Iraq.

The dropping of warning leaflets was not done out of humanitarian concerns: for the British it was strategic, since causing excessive casualties was understood as a source of ongoing resentment and thus further trouble. It isn’t hard to see the parallels with modern military strategy. The same techniques are still, in essence, used by many modern militaries, often in the very same areas where they were originally developed. The continuous bombing of Iraq and the imposition of the no-fly zone between the first and second Gulf wars was a modification of the doctrine, and the leafleting of Iraqi cities such as Fallujah was absolutely in line with it. The ‘war on terror’ saw the return of air patrols and targeted strikes preceded by warnings to the remote valleys of Waziristan, once the redoubt of Mirza Ali Khan. Across the Islamic world, from North Africa to Pakistan, leafleting followed by bombing has been a regular feature of Western policy, the leaflets sometimes serving as a pseudo-legal device to open up free-fire zones where anyone remaining after the warning has expired is considered a legitimate target: their deaths are their own fault.

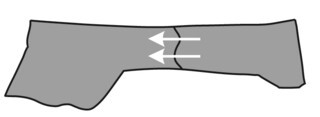

The thousands of leaflets recently dropped by the Israeli air force over Gaza, instructing civilians to leave the entire northern part of the Gaza Strip, contained the following message:

Dear Residents of Gaza

The terrorist organisations have started a war against the State of Israel, and the city of Gaza has become a battle zone. You must evacuate your home immediately and go south of Wadi Gaza.

For your safety and security:

- You must not return to your home until further notice from the Israel Defence Forces.

- Public shelters in Gaza must be evacuated.

- Do not approach the security fence. Anyone who approaches the security fence puts himself in mortal danger.

For your own safety and the safety of your families, you must evacuate your homes and go south of Wadi Gaza.

The Israel Defence Forces

Below the text was a diagram, in case the message wasn’t clear.

The leaflet would have been recognisable to Air Commodore Chisman except in one very important respect: the British were brutal, but they acknowledged that the land belonged to whomever it was they were bombing. They expected them to return home once it was over.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.