In the mid -1990s, I bought a watercolour from a pleasantly ramshackle antique shop I used to frequent in Walmer. It shows two boats, a yacht and a two-funnel liner on a choppy sea, and has a hefty but cheap gilt frame. The painting is done in a flat, naive style, reminiscent of Alfred Wallis, though the colours are not like his and anyway it is signed. The initials ‘S.B.’ in a careful round hand are prominent in the bottom right corner. When I got it home, I saw there were brown mould spots on the sky area and I asked a picture framer I knew, who also did restoration, to see if he could stabilise it. He returned it to me with a curious expression, somewhere between a smile and a smirk. There was, he explained, no mould. The brown spots had been painted on deliberately. He also suggested that the initials ‘S.B.’ stood for Sexton Blake, which is rhyming slang for ‘fake’, and was the monogram used by the forger Tom Keating, after he got caught, to indicate his own work. I think the framer was expecting me to be disappointed, but I was thrilled. The picture is not as old as I imagined. I thought it was early 20th-century whereas Keating only started signing his work after 1977. That didn’t matter. My anonymous little picture had acquired an author and a story. It was part of the newspaper sensation of the 1970s and 1980s which saw Keating’s criminal career exposed, largely through the diligence of the art critic Geraldine Norman, who had become suspicious about the number of Samuel Palmers coming on the market. She later helped Keating write his autobiography and he went on to have a career as a minor celebrity with his own television show.

Did I like my picture more because of what I knew about it? Visually it was unchanged, though I now looked at the brown spots differently and I realised that the frame was part of a deliberate attempt to imply a prewar date for the painting. On the whole I liked it as much as an image, but I felt fonder of it as an object for knowing its history. The purist line of argument holds that what we know, or think we know, about a picture or an object should not affect an aesthetic judgment. But, the counter-argument runs, could there ever be a solely aesthetic judgment? In the philosophical debates about the psychology of perception that raged in the late 18th century, Uvedale Price made the point that a slight sketch by a great artist is always more sought-after than a finished piece by an obscure one entirely because of its associational value. A small watercolour seascape by John Constable, though unfinished, trails clouds of reflected glory from the familiar Romantic landscapes and the atmospheric intensity of his big ‘six-footer’ canvases. If, however, paper analysis reveals it to be a work of the 1840s, probably by Constable’s son Lionel, it suddenly looks rather thin and uninteresting. Just such a ‘forgery in the manner of John Constable’ features in the Courtauld Gallery’s immensely entertaining exhibition Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection (until 8 October), with a caption explaining that Constable’s family came under pressure from dealers after his death in 1837 to attribute as many works to him as possible. The aesthetics of association translate into hard cash.

The show explores the tortuous ramifications of ethics and aesthetics, crime and connoisseurship, in relation to specific works of art, some of which the Courtauld acquired as acknowledged fakes for study purposes, while others were bought in innocence or bequeathed by unwary collectors. There are a few horrors. It is hard to see how Mark Gambier Parry, whose bequest included a specimen of 19th-century Venetian tourist pottery from which someone had scraped off the factory mark, could ever have believed it was a piece of Renaissance majolica with a contemporary portrait of the doge Marco Barbarigo. But most of the exhibits are awful warnings against complacency. Visitors are invited to try their own eye with a couple of forgeries shown beside genuine pieces. I got the Tiepolos right but was stumped by the Constantin Guys, having never looked at his work before. Ignorance, greed and optimism are the criminal forger’s friends and there is a calculation to be made in balancing them. A relatively minor artist such as Guys will fetch less than a Michelangelo but will be easier to pass off – though the show does include a putative Michelangelo sketch on which opinion is still divided. The key moment of opportunity may come when a neglected artist becomes suddenly fashionable, so that demand is high but scholarship still limited. Whoever knocked up the jaunty ‘Breughel’ A Religious Procession took advantage of the rediscovery of his work in the 1920s. The caption doesn’t say where it was done, but the vivid, Kandinskyesque palette smells strongly of interwar Europe. It is one of the peculiarities of fakes that they sometimes reveal themselves simply through the passage of time. Some of Han van Meegeren’s ‘Vermeers’, painted in the 1930s and 1940s, with their angular faces and hard shadows, now look positively Art Deco.

Not all are so easy to spot. The Courtauld has done something of a retouching job on the history of its own van Meegeren, a copy of The Procuress (c.1622) by Dirck van Baburen. The caption states that it was ‘known to be a forgery’ when it was given to Geoffrey Webb, a professor at the institute, who donated it to the collection in 1960. This was not the impression given to viewers in 2011, when the picture was the subject of the first episode of the BBC series Fake or Fortune. At that point the Courtauld claimed to be unsure of its authenticity. Analysis of the pigment revealed that it included Bakelite, a plastic patented in 1909 and useful for hardening paint quickly. The picture had been given to Webb, who played a prominent role in the postwar recovery of artworks looted by the Nazis, as a thank-you gift by a Dutch colleague. Whether the colleague knew it was a forgery isn’t clear. But none of this has harmed the Courtauld because, as the dealer Philip Mould revealed to an astonished Fiona Bruce in Fake or Fortune, van Meegerens fetch more these days than Baburens. Van Meegeren’s career vividly exemplifies the corkscrew character of the forger-as-artist. He was put on trial after the war for collaboration, having sold a Vermeer to Hermann Göring, but got off when he explained in court that it was a fake and claimed he had done it to help preserve Holland’s genuine heritage. He duly became something of a national hero for having conned Hitler’s vice-chancellor. More difficult to explain was the copy of a book of his own designs found in the Reich Chancellery, inscribed: ‘To my beloved Führer in grateful tribute, from H. van Meegeren, Laren, North Holland, 1942.’ With remarkable sangfroid van Meegeren claimed that the inscription was itself a forgery – and he was, in some quarters, believed.

The two principal motives that fakers give, according to the exhibition, are financial gain and a desire to ‘fool the experts’, the latter as complex and diverse in its implications as the former is straightforward. If anyone ever did fake pictures solely for the money there aren’t many examples here. One possible exception is the chalk drawing of a head that was one of 2400 works supposedly by Corot that appeared in the 1920s and were said to have been left in his studio at the time of his death in 1875. The story that they had been concealed ever since by his landlords was exploded with relative ease.

The forger usually has more convoluted reasons and half a wish to be caught. A particularly flagrant case from the 1890s was Icilio Federico Joni, who appears in the exhibition in a sepia photograph looking winsome in doublet and hose. Joni took the late Gothic Revival to its most literal extreme with his ‘early Italian’ religious pictures, of which a plausible example, in the form of a small triptych, is included in the show. There is often such a streak of exhibitionism in the forger, who may become their own most elaborate creation. Tom Keating put himself forward as a humble backroom restorer outraged by the machinations of an art world that passed off paintings as originals when they had been so heavily repainted as to be in effect reproductions. He made much of the fact that he never took money for his pictures. What he thought about the collectors who were later duped into buying them or the innocent students and visitors who saw them in public galleries is less clear. Like van Meegeren, he became a kind of Robin Hood folk hero, the little man – and nearly all forgers, at least those who’ve been caught, are men – against the establishment.

But the forger’s forger, strongly represented in the show, struck a different pose. Eric Hebborn was an alumnus of the Royal Academy, a friend of Anthony Blunt and the perpetrator of countless bogus Old Master drawings. Although he confessed, Hebbborn was never charged with any criminal offence. Too many personal and institutional reputations were at stake for anyone to want to cast the first stone. In 1991 he published an autobiography, Drawn to Trouble, in which he denounced the art market and later turned the tables on his victims, including the Courtauld, by ‘confessing’ to authorship of genuine works in their collection. The show includes a street scene by Guardi that Hebborn said was one of his, thereby forcing the Courtauld onto the defensive and making it prove its own case. It was able to do so by means of photographic evidence dating from before Hebborn was born. He didn’t have the last laugh. In 1996, shortly after his manual The Art Forger’s Handbook was published in Italian translation, he was found collapsed in a street in Rome suffering from severe head wounds and died three days later. Claims and counterclaims about his work continue to echo uncomfortably through an art world that, with the commendable exception of the Courtauld, would generally prefer to forget the whole thing.

Keating had a scale for assessing pictures that were not what they appeared. It went from mistakes (innocent copies that were later misattributed), to over-restored originals, to intentional fakes, and finally to full-blown forgeries, for which the deception extended beyond the object itself to the creation of a false provenance. There are examples of all levels in the exhibition, though it’s hard to define a pure mistake. At the innocentish end is George Romney’s pen and ink Study of the Conjuring of a Spirit from the Play ‘Henry VI’, to which the bookseller Walter Spencer added the initials ‘W.B.’ in the belief that it was by William Blake. Spencer was prone to such improvements and, as the caption admits with a note of resignation, ‘other spurious signatures on original drawings in the Courtauld collection’ can be traced back to him. At the most elaborate end are carefully re-created studio stamps and mounts made to suggest that a picture has passed through a respectable private collection. The 19th-century sculptor Egisto Rossi, who had a sideline in fake drawings, went so far as to improve a putative Giuseppe Passeri Virgin and Child with St John with a mark in the corner suggestive of the Medici coat of arms.

But there are some kinds of fake that are all but impossible to prove, either in a gallery or a court of law: what might be called remote forgeries, which need involve no physical contact with an artwork. The reputation of the American art historian and connoisseur Bernard Berenson was badly dented when his private arrangement with the dealer Joseph Duveen came to light. Berenson received 25 per cent of the price of works he authenticated and grew rich on the proceeds of what subsequent research has suggested were sometimes highly optimistic attributions. Connoisseurship has been out of favour in recent years, tainted partly by suspicion of conflicting interests, both financial and academic, and also by resentment of the fact that it is the province of an elite. The continuing row about the presently invisible putative Leonardo da Vinci, Salvator Mundi, has done nothing to restore faith in expert assessments.*

As the Courtauld exhibition and successive series of Fake or Fortune illustrate, technology is becoming both more useful in detecting forgeries and more trusted. An X-ray of the Joni triptych shows the modern nails holding it together. At this point one might wonder why, if the only demonstrable difference between this and a medieval piece is some usually invisible nail heads, the cocktail of information and association that makes up ‘authenticity’ matters, beyond its effect on the price. The answer, the exhibition argues by implication, is that it matters for the understanding of history and of the work of individual artists. Describing a fake Rodin drawing, the Courtauld points out that the ‘lumpy female nude’ is ‘awkward and wooden’ and so not by Rodin, a judgment that depends on there being enough real Rodins to know that, even on an off day, he was never as bad as that. If accepted as genuine, Joni’s rather lovely soft-eyed Virgin, with her Pre-Raphaelitesque companion saints, would have slightly shifted our understanding of medieval aesthetics and religious imagery and over time allowed for more misattributions by comparison, until a whole piece of the past was significantly skewed.

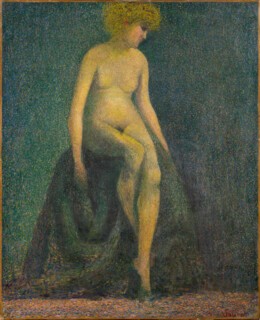

The most tantalising picture in the show balances on this knife edge. Nude with Blonde Hair was bought as a Seurat by Samuel Courtauld himself. He had been told by Seurat’s friend Félix Fénéon, who catalogued his work, that it was genuine, an early painting done as Seurat was formulating his pointillist style. The caption points out that the signature is a later addition, but the main objection to it – what makes it ‘one of the most puzzling works in the collection’ – is its ‘poor quality’. But the argument that it isn’t by Seurat – even when young and in a formative stage of his career, because Seurat never painted anything so bad – is circular. Fénéon knew him. My bet is that it’s genuine.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.