There have been two recent opportunities to see Richard Mosse’s remarkable work in London. Broken Spectre (2022), a film and series of photographs, was displayed earlier this year in an echoing, pseudo-industrial basement space at 180 the Strand; the Hayward Gallery’s ecologically themed group show Dear Earth, which runs until 3 September, includes the related but more austere multiscreen Grid (Palimi-ú) and photographs taken on the Rio Tigre in the Peruvian Amazon. All these works involve stark confrontations with an Amazonian terra atrocitatis, in which extractive industries work with antinomian fury to create fields of toxicity and death amid the planet’s most abundant concentrations of life. Together, they document what amounts to an act of negative creation, an anti-Genesis.

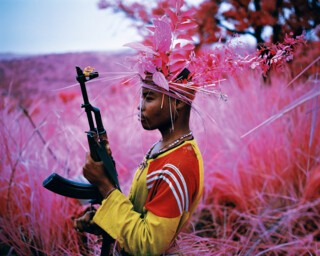

Mosse seeks what can’t be seen. He employs military or industrial camera technologies sensitive to light spectra invisible to the eye; his subjects are ignored or remote catastrophes. His photographs of the war in Congo for The Enclave (2013) were created with Kodak’s discontinued Aerochrome film stock, a ‘false-colour’ infrared film that reproduced the deep greens of the Congolese jungle as hot pinks and purples. Aerochrome originally had military applications: it was used to detect enemy emplacements camouflaged with foliage. Repurposed by Mosse, the film produced an aestheticised theatre of war, with child soldiers, bullet-riddled corpses and squalid refugee camps set in a candyfloss landscape, as flamboyantly neo-chromatic as a Kinshasa sapeur.

The drone-borne multispectral cameras used for the aerial photography of both Grid and Broken Spectre were designed by Mosse and his team. Like Aerochrome, they produce false-colour representations of wavelengths invisible to the naked eye, so foliage shows up in lipstick scarlets, saturated orange, pinks and purples. Versions of the same technology are used in military reconnaissance and on satellites that measure solar radiation from the Earth’s surface, producing data that can be used by scientists to study, for instance, damage to forest cover. Similar drone-mounted cameras are used by farmers to check crop health from the air, and one of the first photos in Broken Spectre is of a billboard advertising agricultural drones for use on the vast monocultural farms of soya and palm that are eating into Amazonia. ‘Our Technology Makes Your Profit Sprout,’ the legend reads, a formulation that confuses the financial and the organic, while hi-tech industrial agriculture – or ‘precision farming’, as the drone industry styles it – advances through the rainforest.

The images were all made in remote parts of the Amazon: the Mato Grosso, Rondônia, Cuiabá – the same places whose lost isolation Claude Lévi-Strauss lamented in Tristes Tropiques. In Broken Spectre, they are of three varieties: close-up images of jungle life; composite multispectral images of the jungle from the air; and black and white infrared images of the human beings who live and work in the jungle – both the frontiersmen who work the ranches, gold mines and logging stations and the Indigenous Yanomami. The humans and their baleful work are shown at intermediate size (what we might think of as a ‘normal’ size for photographic reproduction); around their monochrome industry and misery Mosse veers between very small things made enormous and enormous things made very small. The images of life include a leaf-like katydid squatting among some scrotal miniature pitcher plants, and a mantis elegantly goal-hanging on a bundle of Venus flytraps. Shot at night with an ultraviolet lens, these photographs are saturated with hallucinatory colours; the impression is of burgeoning and utterly alien life, on a scale so small and so abundant as to disorient the human viewer.

This is part of the point: Mosse is trying to show complex ecological and historical processes taking place beyond perception and representation. The aerial photographs lift us away from the miniature universe on the jungle floor to take in a drone’s-eye view of huge swathes of forest, where the camera’s novel colour range distinguishes distressed vegetation from healthy forest. The violent attacks that the Amazon has sustained start to become clear. Fires rage, both through the jungle and, hellishly, below the earth: in the Pantanal, the world’s biggest wetland, dry seasons are now so extreme that fires break out underground, coursing through desiccated root systems. They are nearly impossible to fight. Gold mining is conducted in the Amazon by hosing sediment into waterways under extreme pressure. The mud appears white in Mosse’s camera lens, the spoil-clogged rivers chalk-blue. This is river and forest transformed into a filthy toothpaste moonscape. Oil palm plantations spread into the jungle like a pink fungus; the regimented rows of trees are a million asterisks, a continuous stream of obscenities.

Scattered throughout are images of the people at the centre of it all: the garimpeiros or illegal gold miners, fixing the tiny amounts of flushed-out gold with mercury, and poisoning themselves and the river as they do so; the Yanomami, trying to protect the forest and their people from the incursions of loggers and miners; and ‘burners’, posing in front of the primary forest they are about to incinerate. These are Mosse’s perpetrators and victims, the mediators of life and death in the jungle. We are looking at the blazing, contaminated, violent frontier of a planetary-scale disaster.

The photographs are too beautiful, however, to convey the horror fully: they show disasters, but they also lift us out of them. Their prettiness speaks as much to desktop wallpaper aesthetics as to the military-scientific origin of the technology. Perhaps Mosse intends this: the destruction his pictures document doesn’t sit easily with their probable destinations – the art gallery, the collector’s house. Planetary doom through a pink filter is a great commodity.

But this knowing art-world ambivalence is abandoned in the films, which are terrifying, direct and refuse to sustain such games. Grid comprises aerial drone shots of palm plantations, cattle ranches and mining sites, presented as a shifting, sixteen-screen patchwork. It is offset by a widescreen film of Yanomami men in the village of Palimi-ú. Blackened with charcoal and dressed in ceremonial finery, they declaim their desperate condition to the camera, and plead for help against the violence of the miners. Meanwhile the multiple screens flicker like a CCTV surveillance array, capturing crimes about which nothing is being done. ‘We don’t want to be filmed for nothing, as usual,’ one of the men says. ‘You must come quickly and help us … or did you just come here to see and film for no reason?’

Broken Spectre makes for harder viewing still. Playing on a continuous loop across a split screen, and accompanied by Ben Frost’s fear-inducing soundtrack, the world pictured is one that has been plunged into the abyss. Two burners, faces wrapped in cloth against the smoke, race between piles of freshly felled vegetation, spraying petrol onto the leaves and lighting them with burning brands. The flames rise, engulfing the forest in smoke. Three cowboys ride through lush forest, before their path opens onto the carbonised wasteland they have created, desolate as far as the eye can see. Hundreds of dewlapped, doe-eyed cattle are herded through the burns, grazing where they can; later we see them lined up in panic for the bolt-gun. Slaughtermen swiftly set about working the warm carcasses with knives, dragging flayed hides across the gore-stained floor, chainsawing bodies in two. Loggers fell forest giants for the camera; each lands with a sound like a bomb going off. A gigantic, gnarled rotary drill is slowly lowered into a pristine waterway; a pair of black-necked Jabiru storks on the river bank are shaded by darkening clouds; the skeletal trunks of the dam-submerged forest shimmer in the swollen water. A tide of murders covers the landscape, and aerial footage shows us the devastation left in its wake. There is not a scrap of green in the film; in the multispectral eyes of Mosse’s camera, the trees that still stand are fiery red.

If this sounds apocalyptic, that’s because it is. Ecocide and genocide come together in Amazonia: colonisation is an unfinished project in the world’s last great inhabited wilderness, and the film’s occasional drift into the cinematic register of the Western is deliberate. Mosse includes sequences showing the abject poverty of the burners and cowboys, and the pitiful nuggets of bullion dross scummed by the garimpeiros; they may seem like gleeful devils, but responsibility for their actions lies far higher up the chain. It extends into the darkness of the gallery: London’s smooth and level pavement was raised by the same infernal principles.

At the centre of the maelstrom is a speech by Adneia, a young Yanomami woman. In one of those dramatic accidents that so often attend filmmaking, Mosse’s reel runs out in the middle of her declamation, leaving the screen in darkness for several minutes as she castigates Bolsonaro, who unleashed frontier capitalism on her people with renewed ferocity. Like the men in Grid, she tells Mosse not to film her if he’s not going to do anything. ‘You white people, see our reality,’ she says. ‘Open your minds. Don’t let us talk so gallantly and do nothing.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.