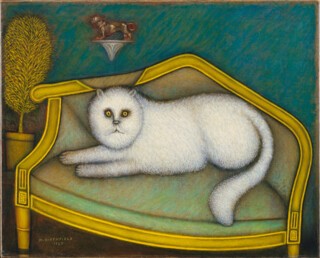

In 1939, the American collector Sidney Janis was asked to curate a show of work by unknown artists for the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He visited the Hudson Walker Gallery on 57th Street, but found nothing he wanted to include. On his way out, however, he noticed two paintings turned to face the wall. The gallery owner explained that they were not worth seeing, but Janis insisted. ‘What a shock I received!’ he later wrote. ‘In the centre of this rather square canvas, two round eyes … were returning my stare! They belonged to a strangely compelling creature which … immediately took possession of me. This was my introduction to the work of Hirshfield.’

The strangely compelling creature was Angora Cat, one of only two paintings Morris Hirshfield had begun before 1939. He was 67. In the seven years before his death in 1946, he painted almost eighty more. Angora Cat carries a strange psychological charge. A white cat with electric yellow eyes sits on an Art Deco sofa, beneath a small figurine of a lion. The curvature of the couch warps the perspective and the cat is much too big for its seat. Its fur is made up of hundreds of tiny strokes of paint; the result, Hirshfield believed, ‘was better than a camera could do’. Angora Cat was painted over a picture by an unknown artist that Hirshfield’s wife, Henriette, had framed and hung in their apartment in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Part of the underlying painting – the lion figurine – remains visible; he integrated it into the picture just as he did in Beach Girl, the other painting Janis found at Hudson Walker Gallery, where a girl’s face peers through layers of paint.

When the paintings were exhibited in Contemporary Unknown American Painters at MoMA later that year, the press took these features as evidence of Hirshfield’s ignorance and limited technical abilities; a self-taught artist, the critics argued, he probably couldn’t paint either lion or face so decided to keep the ones he found. In Master of the Two Left Feet, Richard Meyer tries to show that these compositional strategies actually reveal Hirshfield’s knowledge of art history and the way paintings work. The vogue in the 1930s and 1940s for unknown, native and ‘primitive’ art means that Hirshfield is remembered (when he is remembered) as an unworldly Jewish tailor who one day decided to pick up a paintbrush. In Meyer’s account, however, Hirshfield was a canny operator who knew how to play on distinctions between high and low culture.

Born in 1872, Hirshfield emigrated to New York from Poland when he was eighteen, one of many Ashkenazi Jews escaping persecution in Eastern Europe and Russia. He changed his name from Moishe to Morris and found a job in the rag trade, working as a pattern cutter in a women’s suit factory on the Lower East Side. Soon he had saved enough money to leave the factory floor and with his brother, Abraham, opened a women’s clothing store called Hirshfield Brothers. In 1912, Hirshfield, along with Henriette, Abraham and their sister, Bertha, opened E-Z Walk Manufacturing Company, a wholesaler specialising in orthopaedics and slippers for women. Between 1913 and 1934, Hirshfield patented 24 designs for orthopaedic foot devices and slippers; the latter were variously adorned with buckles, pompoms, straps, bows and classical figures. Janis joked that Hirshfield’s habit of painting women with two left feet could be attributed to the fact that slipper samples ‘were made in left feet only’. (Among other anatomical idiosyncrasies, Angora Cat has two left paws.) The patents, which included ankle straighteners, arch supports, shoe inserts and heel cushions, made him rich: E-Z Walk grossed more than a million a year in the 1920s and survived the Great Depression.

In the mid-1930s, Hirshfield fell ill and the company went bankrupt. For a while he worked as a ‘foot appliance consultant’, but the money wasn’t good and the Hirshfields were forced to move from affluent Borough Park to a small flat in Bensonhurst. It was here that Hirshfield took up painting, working for ten hours a day in his bedroom, much to his wife’s annoyance. It took him years to finish Angora Cat and Beach Girl. Henriette’s feelings changed as his paintings gained recognition; his first solo show opened at MoMA in June 1943. Though his reception was always mixed – he was celebrated by Clement Greenberg but derided by the press – it was a remarkable achievement for a tailor and businessman whose only previous artistic efforts were two wood carvings he made as a boy.

Hirshfield owed his success almost entirely to Janis, whose career trajectory was similar to his own. After a brief stint as a ballroom dancer, Janis worked in his brother’s shoe business and went on to set up a shirting company – M’Lord Shirts – which catered to the aspiring middle classes (it was the first company to sell shirts with two breast pockets). The venture was so successful that its sale allowed Janis and his wife, Harriet Grossman, to spend the rest of their lives collecting art and writing books. By the early 1930s, they had acquired major works by most key modern European painters, and in 1934 Janis was invited to join the MoMA advisory committee. He would later donate a large part of his collection to the museum, including Angora Cat.

Janis’s passion for modern art was matched only by his love for artists he called ‘self-taught’ (preferring this term to ‘primitive’ or ‘naive’), who in the late 1930s and early 1940s formed a cornerstone of MoMA’s exhibitions programme. Exhibitions such as American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America, 1750-1900 (1932-33) and Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America (1938) introduced the public to a number of these artists, making an aesthetic claim for unschooled painting (Janis wrote a catalogue essay for Masters of Popular Painting on Patrick J. Sullivan, an American house painter turned artist he described as ‘gentle’ and ‘unspoiled’). Masters of Popular Painting was the third exhibition to survey the major movements of modern art at MoMA; the first, Cubism and Abstract Art, was held in 1936; the second, Fantastic Art: Dada, Surrealism, opened the same year. It was followed by two survey exhibitions, both organised by Janis, that included paintings by John Kane, Horace Pippin, Anna Mary Robertson Moses (aka ‘Grandma Moses’) and Hirshfield. In They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century (1942), Janis described them as ‘artless, ingenuous, refreshingly innocent’, successors of the itinerant portrait painters and craftsmen of the 18th and 19th centuries. In the preface, Alfred H. Barr wrote that Janis identified with these artists: he, too, had learned his trade informally and attributed his success to intuition and the strength of his convictions.

Janis took Hirshfield’s work to Europe, where he showed it to Picasso and Giacometti. He persuaded Peggy Guggenheim to buy Nude at the Window (Hot Night in July) for $900, far more than she had paid for paintings by Mondrian ($160) and Magritte ($75). Barr described Janis as ‘the most brilliant new dealer, in terms of business acumen, to have appeared in New York since the war’, but it’s not clear why Guggenheim spent so much on the painting. She eventually sold it back to Janis – perhaps, Meyer suggests, because she was upset by a photograph taken by Hermann Landshoff in which Breton, Duchamp and Ernst (her soon to be ex-husband) stand behind Nude at the Window, while Leonora Carrington sits on a rocking chair with a stone phallus between her legs. The split with Ernst was acrimonious, not least because Guggenheim believed her husband was still in love with Carrington, with whom he’d once been involved. Meyer interprets the photograph as ‘an elaborate joke’ at Guggenheim’s expense.

Meyer is particularly taken by Hirshfield’s relationship to Surrealism, dedicating a considerable portion of the book to his inclusion in First Papers of Surrealism, an exhibition held in New York in 1942. Curated by André Breton, it included works by Carrington, Ernst, Frida Kahlo, André Masson and Yves Tanguy. Hirshfield was invited to exhibit Girl with Pigeons (1942), a painting in which a female figure lies on a red striped sofa, surrounded by pigeons and decorative palm fronds. As Meyer notes, it is likely that the girl and the pigeon near her mouth were painted with the canvas positioned vertically, before Hirshfield turned it onto its side to finish the picture. For Meyer, this makes the painting ‘pleasurably off kilter’; to my eyes, it’s simply obtuse.

In ‘rediscovering’ Hirshfield, Meyer has tried to expand the narrative of interwar American art, arguing that Hirshfield is an important, if neglected, figure in its history. Given the prominence of ‘popular painters’ or ‘modern primitives’ in the period, it is surprising that there is no mention of them in the diagram Barr drew for the Cubism and Abstract Art poster (although Rousseau is given his own place). Instead, the various modern movements from Surrealism to the Bauhaus resolve themselves finally in Abstraction. That Hirshfield was included in First Papers of Surrealism complicates this closed teleology.

Meyer is at his best when he works to uncover a ‘textile imaginary’ in Hirshfield’s painting. The hair of one girl looks like grey-flecked yarn, the background of another like herringbone cloth. Skies are woven out of wool. A lion’s mane resembles a woman’s fur stole (‘only Hirshfield would invent a lion who not only has fur but wears it’), while the whip held by the driver of a winter sled looks like a giant threading needle. These details help to unravel the paintings from within. (It’s worth noting that the etymology of ‘detail’ comes from tailoring: taillier, ‘to cut in pieces’.)

Meyer is less convincing when he takes Hirshfield’s reception by the avant-garde as writ, especially where there is little evidence. Countering a contemporary critic who demoted Hirshfield’s painting from greatness to folk art, Meyer argues that he ‘neglects to mention that it was Picasso, the most widely recognised living artist in the world, who had named Hirshfield “great”’. There is no reason to doubt Picasso’s feelings, but it would be useful to know why he felt this way. Similarly, Breton declared Hirshfield to be ‘the first great mediumistic painter’, a statement Meyer agrees with, but without asking of what Hirshfield was a medium. The Freudian id? Archetypes? Capitalism? Nor does he ask what kind of unconscious might have motivated Hirshfield’s textile imaginary. Meyer wants to see the paintings ‘through the eyes of Eros’, as Breton saw Surrealism, but figures with two left feet are a prophylactic. Does Nude at the Window really evoke a world of ‘magical pleasure far beyond the quotidian’, ‘a realm beyond reason or recognition’? Does it really give off ‘sexual heat’?

Surrealism suggests a movement away from reality. Hirshfield pulls you in the opposite direction: his paintings are subreal; they lead nowhere but themselves. Guggenheim wrote that when Two Women in Front of a Mirror (1942) hung in her entrance hall the bottoms of both figures received ‘many pinpricks from sensuous admirers’. Janis recalled that Tailor-Made Girl (1939) returned from an exhibition with ‘the nose, which is in relief … blackened by fingermarks’. This fetishistic quality is taken up by Meyer, but dirt and debasement speak more to base materiality than they do to Eros as Breton meant it. Meyer never quite gets there, in part, I think, because he wants to emphasise the anti-intellectual ‘pleasure’ of Hirshfield’s painting, and also because he seems anxious to find a way of legitimising Hirshfield’s inclusion in the modernist canon.

Janis used the expression ‘self-taught’ because it connected the artists he loved to everyday life. Meyer, an art historian from Stanford University, published by MIT, identifies with this tradition: his introduction states that he will forgo academic jargon and his conclusion is autobiographical. Hirshfield was seen as a ‘popular artist’ in the 1940s and Meyer ‘aspires to [write] a work of “popular art history”’: ‘Individuals and events take precedence over arguments or art-historical themes.’ This results in many omissions. While Meyer provides biographical detail and anecdote, he does not discuss the conditions that led self-taught artists such as Hirshfield to come into view only to disappear a decade later. Hirshfield’s show at MoMA in 1943, which was advertised with the subtitle ‘Retrospective Exhibition of Primitive Paintings by Retired Cloak and Suit and Slipper Manufacturer Shown at Museum of Modern Art’, was the last solo exhibition by an unschooled painter at the museum. It was also, as John Brooks wrote in the New Yorker in 1960, ‘one of the most hated shows the Museum of Modern Art had ever put on’, and contributed to Barr’s dismissal as director. Meyer doesn’t address the reasons why such a supposedly popular painter was reviled by the public.

The prominence of self-taught artists in this period can be traced to Roosevelt’s New Deal programmes, including the Federal Art Project, which, in bringing art to community spaces and commissioning work from a wide range of artists, blurred the lines between fine art and the wider culture. The ascent of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s marked the end of this period – it offered a dramatic break with the past, celebrating America’s global ascendancy. The appeal of self-taught artists making it against the odds (Janis never mentioned that Hirshfield was once rich) diminished, as did the attraction of work that appeared handmade, laboured or odd. In the wake of decolonisation and the Great Migration, critiques of modernism’s infatuation with the ‘primitive’ and ‘naive’ also played their part. To weave these kinds of narratives into the account of Hirshfield’s short career as a painter might well make for a more ‘academic’ and less ‘popular’ book, but Meyer risks underestimating the reading and art-going public, who aren’t so pleasure-seeking as to be averse to argument and art history.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.