The magic lantern is a prosaic object: a tin or wooden box, fitted with a chimney, a set of lenses and a light source. But for nearly four centuries it has animated the walls of homes and theatres, first as a device for conjuring demons and later as a form of popular entertainment. It is thought to have been invented around 1650 by the Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens, to whom we also owe the pendulum clock and the discovery of the true shape of the rings of Saturn. Slides are inserted upside down, so that the image projects right side up, and the lantern is positioned at a distance from the screen determined by its lenses. Originally the images were miniatures, hand-painted on glass, but from the 1850s photographic slides began to dominate the market. Full darkness is required for the lantern to work, since even a sliver of light will dilute the projection.

Many of the earliest lanterns were made in Germany in the workshops of the Nuremberg toy makers. Early allusions to projection devices can be found in Giovanni Fontana (c.1420) and Giovanni della Porta (1589), but the first printed description appears in the second edition of Ars magna lucis et umbrae by Athanasius Kircher, published in 1671. Five years earlier, in August 1666, Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary about a man who brought him ‘a lanthorn, with pictures in glasse, to make strange things appear on a wall, very pretty’. During the 19th century, John Ruskin, Heinrich Wölfflin and other art historians used lanterns to illustrate their lectures. Charles Dickens put on shows for his children and called London itself his magic lantern. It ‘sets me up and starts me’, he wrote to John Forster. In Remembrance of Things Past, Proust’s narrator projects toy lantern images into the dark of his bedroom, uncertain where his self ends and the sorcery begins.

Illuminants evolved over the centuries: candle, argand lamp, limelight, arc light, incandescent light bulbs, light emitting diodes. The simplest shows used a single lantern. More sophisticated arrangements, better for spectacles, had two projectors side by side or stacked one above the other. Triunials, or three-tiered lanterns, created the most elaborate effects but were more expensive and harder to master. The most popular special effect, only possible with two or three lenses, was that of dissolving views, in which one landscape faded into another, or day transitioned into night. This technique also made use of an early version of the thought balloon, with an inset hovering above the subject: a girl asleep in a forest dreaming of witches flying overhead, a soldier of returning home. Other effects were produced by moving cranks, levers and handles. Slipping slides allowed for movement back and forth – eyes glancing left and right, rapid transformations. Lever slides created an arc, rotating handles a full circle.

In some cases, the lanternists themselves became part of the lore; the Savoyards, 18th-century itinerant wanderers, would leave their mountain homes in late October to travel the countryside with a magic lantern strapped to their backs, its tall chimney like a ship’s funnel powering their journey. They led a portfolio existence: peep shows by day and magic lantern shows by night, as well as offering their services as chimney sweeps. To judge from surviving engravings, Savoyards often played the hurdy-gurdy and kept as a companion a marmot, a large ground squirrel whose piercing squeaks must have added to the atmosphere. Savoyard lanterns, rough-and-ready objects that bore the marks of weather and regular use, tended to be crudely made and weak in illumination.

From 2019-21, I was writer in residence at the Swedenborg Society, which has hundreds of magic lantern slides in its archive. The director, Stephen McNeilly, invited me to put on a show, and write a series of short pieces to accompany the images in the collection. The society was founded in 1810 to translate into English the works of the 18th-century Swedish scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. Although the slides were made long after his death in 1772, his taxonomic impulse and his investigations into the afterlife make him a fitting presence for a magic lantern show, and the oak-panelled neoclassical hall at Swedenborg House seemed a fitting venue. We contacted Jeremy Brooker, then chairman of the Magic Lantern Society, who along with wife, Carolyn, has been putting on magic lantern shows for decades. They agreed to collaborate. We wanted to offer audiences the full spectacle, to show the different registers the instrument can produce, and so we decided to include some of Jeremy’s slides too, as preludes to my stories. This meant we could show hand-painted slides as well as photographic ones, offsetting contemplative moods with moments of joviality. Many of Jeremy’s slides are playful and nimble, while those from the Swedenborg collection, most of which are monochrome, suggest an otherworldly stillness.

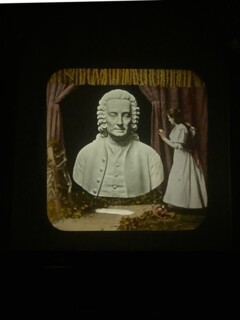

The Swedenborg slides are mostly landscapes, street scenes and scientific diagrams used to accompany lectures. A box labelled ‘Portraits and Busts’ holds dozens of images of former members of the society, a procession of eloquent faces, male and female. Scholars have struggled to learn more about their origins. It is not known when most of the photographs were taken, nor when the slides were made, nor by whom. James Wilson, an editor at the society, recently discovered that the majority of the slides were acquired in 1910 and 1912 by two men from the New Church: the Reverend J.R. Rendell and Alfred Henry Stroh. Rendell had a keen interest in photography; Stroh was an eminent theologian. The only box that can be dated is labelled: ‘Seventy-five Slides, illustrating a Visit to Skandinavia, LECTURE delivered by Dr Freda Griffith, 1952’. Griffith was the society’s secretary for more than three decades and devoted much of her energy to producing a third Latin edition of Swedenborg’s eight-volume Arcana Coelestia (1749). It’s revealing to see what her eye landed on during her travels: libraries, bridges, ships in the harbour. Most of the photographs contain no people, as though taken during a lull in human activity.

The three-and-a-quarter-inch square glass plates were kept in tight rows and had funerary black tape around their edges. I laid out those I found most intriguing: the silhouette of a hatted man under a bridge; vacant rooms with ghostly furniture; a tree-lined avenue with an overturned bicycle. Jeremy and I decided our themes would encompass the passage of time, ghosts and the supernatural, travel (physical and metaphorical) and the natural world (fantastical creatures and natural phenomena). I titled the spectacle ‘Stilled Shadows’, but as time went on I thought more about the movement that would come out of this stillness. A slide is usually projected for around ten seconds, so a five-minute story requires around thirty slides. Different sections call for a faster or slower rhythm; in the right context, an image might linger for thirty seconds or more, especially when accompanied by expansive music. Our show lasted for an hour and used more than a hundred slides.

The first performance took place on 21 October 2021 – the right time of year for summoning spirits. Until that evening, I hadn’t seen any of the slides projected. As I looked up from my text at the images, new details came into view – objects in a room, a face in a parked car. The show was accompanied by the silent film pianist Costas Fotopoulos, but this wasn’t the only sound the audience were attuned to: people later commented on the clacking of the slides, or rather, of the wooden carriers into which the slides fitted. The projection involves a complicated choreography in the dark. One person must insert the new slide as the old one is removed to avoid the dreaded empty circle of light. This is part of the allure of the analogue: it’s impossible to forget the human behind the illusion. In our show, the magic lantern occupies a table at the centre of the room, flanked on either side by rows of spectators, with the mechanism in full view. Rather than detracting from the experience, the exposed machinery adds to the sense of enchantment.

There’s something inherently ghostly about the magic lantern but its most overtly macabre manifestation was the spectacle of phantasmagoria, fashionable in the late 18th and early 19th century. Ghoulish figures were cast onto a translucent screen or a cloud of smoke with the help of a fantascope, a lantern on wheels that could zoom in and out, allowing the phantoms to grow in size as if rushing towards the audience. These shows were accompanied by the strains of a glass harmonica and clanking chains, thunder, church bells. The lantern would be concealed, the source of projection a mystery. The most celebrated phantasmagorist was the Belgian showman Étienne-Gaspard Robertson, who installed himself in the Capuchin Convent in Paris after the French Revolution, resurrecting traumas not yet laid to rest.

The ghosts in our magic lantern show are quieter. They haunt their spaces unobtrusively, they invite us to make psychological readings of inanimate objects. Among my stories is one about a reclusive writer who leaves home to search for her missing cat, and wanders through her past as she roams the city. Another woman, feeling captive to the fine flat she has inherited, begins to perceive an unsettling presence in a marble-topped table. A slide with the handwritten words ‘The Mechanism and Substance of Mind’, the title of a lecture on Swedenborgian theory, leads to a vignette about a young woman who is prey to a deepening solitude. A slide showing a pair of old-fashioned Swedish phone boxes, one for local calls, one for long distance, inspires a dialogue, each phone box given its own musical identity. As the stories unfold, the focus moves from individual portraits to a wider vision of the cosmos.

Today, the magic lantern is kept alive by the UK’s Magic Lantern Society, which hosts regular meetings, provides online resources and publishes a quarterly journal listing forthcoming shows, exhibitions, restoration tips and sightings of lanterns in recent films or TV programmes. Many of the personal ads are performances in themselves: ‘Young(ish) female member, five foot one, seeks Magic Lantern chimney maker to create stunning new chimney for wooden lantern. Current tea-towel chimney substitute lets out light and is becoming singed’; ‘For sale: Hand-painted double slipper slide: acrobat arches himself for vertical take-off, he succeeds only to tip over and land on his face. Excellent condition. £30.’

My modest collection of slides includes a painted portrait of the sun, captured on a summer’s day long ago. I bought it last year during a meeting of the society (at the back of the room, tables were set up with items for sale or barter). The sun is surrounded by an orange halo, billowy purple clouds and a sky in different shades of blue. The sun’s centre is transparent, allowing it to take on the colour of whatever background it is set against. Along the bottom of the frame is written in black ink: ‘The Sun as on 3o July 1817’. If you look closely you can see four sunspots, and perhaps something more, impossible to read with the naked eye. I have yet to see it projected.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.