The most unexpected building in Port Glasgow is a castle – Newark Castle, inherited in the 17th century by the Maxwell family, who turned it from an austere tower house into what the guidebook calls a Renaissance mansion. The Clyde rises and falls only a few yards from the castle’s back door, and in 1668 Sir George Maxwell sold eighteen acres of riparian land to the city of Glasgow, which thought it was a useful site for a harbour. Shoals and shallows above that point in the river made Glasgow inaccessible to sea-going ships; they usually transferred their cargoes at Greenock, three or four miles further west, to smaller vessels, barges and wherries that were rowed or poled the final twenty-odd miles to the Glasgow warehouses. Greenock’s near monopoly in the transhipment business irritated Glasgow’s merchants and civic officials, and disputes over taxes and tariffs frequently broke out. The New Port of Glasgow cut out the vexatious Greenock middleman.

In the 1950s I spent several holidays in Port Glasgow, in the tenement flat of my aunt and uncle and their two daughters. Its importance as a port had died long before. The boom years began with the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, which allowed Scottish merchants access to the New World’s tobacco, sugar and cotton, and drew to an end late in the same century when the Clyde was deepened to allow transatlantic ships and their cargoes to reach Glasgow directly. Port Glasgow found its future as a shipbuilding town, making its mark in industrial history and the pantheon of Scottish innovation by launching Europe’s first commercial steamship, the Comet, in 1812. Migrant workers arrived from the Highlands and the rural Lowlands, and especially from the place Victorian writers nicely called ‘our sister isle’. It became known for a time as the most Irish town in Scotland. Shipyards, quays and graving docks squeezed together along the flat coastal strip to the north of the railway, while tenements, some of them spectacularly sited, lined the slopes that rose steeply to meet the Renfrewshire moorland. This was more or less the town as I first saw it. It seemed impossible that there could be a castle in such a workaday place, where the clamour of the shipyards reached into every street and black smoke plumed from the trains that bustled to and from Glasgow. But there, squashed between two shipyards, almost as if it had been built after them, stood Newark Castle.

Port Glaswegians felt the castle conferred romantic credentials on a place sometimes known as ‘the dirty wee Port’, and my cousins were proud to take me there on a fine afternoon in the summer of 1955, one remembered in Scotland for its long procession of warm and cloudless days. We climbed stone stairs and looked into bare stone rooms. It was tremendously dull. Everything of interest lay outside. I was ten and keen on ships, and through dusty windows I could see a much more attractive world, and hear it, too – steel plates glinting in the sun, still to be fitted lifeboats, the fizz of welding torches, the juddering of rivet guns. The shipyard of James Lamont and Co. bordered the castle on its upriver side. Downriver, and even closer, lay the Ferguson Brothers yard. The ships built at both yards were small – 300 feet long at most – and had humdrum purposes: ferries, tugs, minesweepers, dredgers, the sludge boats that took the sewage from Glasgow and dumped it in the outer firth.

The bigger and more glamorous yards lay upriver at Dumbarton and Clydebank, where John Brown’s built the Queens for Cunard, and inside Glasgow’s city boundaries, where five or six companies on both banks (among them Harland & Wolff, Fairfield and Barclay Curle) gave Auden his ‘glade of cranes’. Downriver, the engine works and slipways of Lithgows, Scotts and the Greenock Dockyard Company shared the waterfront that stretched between Port Glasgow and Greenock. These names and others (in 1955, the Clyde had 22 shipyards) could be found on the builders’ plates of passenger and cargo liners, tramp steamers, river steamers, cross-channel packets, oil tankers, bulk carriers and every kind of warship.

As it happened, 1955 was the best year for Clyde shipbuilding since the Second World War, with 91 ships launched and enough on order to keep the yards fully occupied for the next five years. Even so, competitors in Europe and the Far East had begun to capture some of the river’s traditional customers, and the postwar figures were a long way short of those in its remarkable heyday. In 1891, for example, forty Clyde firms had launched 336 vessels, a typical annual output for the period 1889-1914 when every year the Clyde contributed between a fifth and two-fifths of the world’s new merchant ship tonnage. Nowhere else in the world had such a concentration of shipbuilding, and nowhere else was the industry so celebrated. This astonishing dominance wasn’t likely to return, but the memory of it sustained the notion of the Clyde’s prowess: that its workforce was especially skilled and made particularly sound ships. ‘Clyde-built’ remained a proud endorsement. Long after merchant shipbuilding departed the United Kingdom as a serious industry, people spoke of the river’s ‘great traditions’ as though they might have a practical application at some future point; as if the skills of a lost industry hung over the Clyde like a miasma, ready to be absorbed by a new generation with a genetic disposition to welding and engine-fitting.

Today, the river has two yards left. The first lies far upstream – about as far upstream as a ship can sail these days – in Govan, where the defence contractor BAE Systems makes warships for the Royal Navy on the site of the old Fairfield yard. The second is Ferguson’s in Port Glasgow, the last merchant shipbuilder in Scotland and one of only three to survive in the United Kingdom. Ferguson’s is now notorious in Scotland as the scene of a debacle – the ‘ferry fiasco’. Two vessels that the yard was contracted to build in 2015 will be delivered five years late, at a cost estimated at £250 million, roughly two and a half times the original budget. New dates have recently been set promising delivery next year, and a new chief executive talks confidently of securing the yard’s future. Only a few months ago that looked unlikely. The bigger possibility was that the ships would never be delivered, that the Scottish government would have to write them off and close the yard that struggled to build them.

Few of those involved emerge well from the story, but the charges against the SNP government in Edinburgh are the most serious. Accused of incompetence, evasion and the misuse of taxpayers’ money, the first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, and her colleagues have responded by talking about ‘learning lessons’, ‘saving jobs’ and ‘moving on’. Having renewed her demand for a second independence referendum, Sturgeon needs to demonstrate that her administration is more competent, transparent and responsive to local needs than the UK government. Scottish contempt for the Westminster political leadership reached new heights under Boris Johnson (and threatens to rise even further under Liz Truss), so this should be easy enough. But the SNP has held power in Scotland for fifteen years and has its own list of embarrassments, notably in the areas of public health, education and industrial policy. Compared to low life expectancy, the highest rate of drug-related deaths in Europe and the near total foreign ownership of aquaculture and renewable technologies, the ferries are a minor failure. Only the thinly populated peninsulas and islands of western Scotland are directly affected; a resident population of at most seventy thousand. What makes the ferries so potent politically is that they concretely encapsulate government ineptitude. The Scottish government commissioned and funded the ships; the Scottish government now owns and manages the shipyard: the Scottish government will subsidise the ships when (though ‘if’ still can’t be ruled out) they are in operation.

There are also two romances in play. The first is industrial: these may be the last merchant ships the Clyde ever builds and therefore ‘ane end o’ ane auld sang’ in the phrase used to describe the end of Scottish sovereignty in 1707. The second is Hebridean: the fifty inhabited islands that make their ragged pattern off the west coast have since the 18th century established themselves in the European imagination. Seagirt and empty, with crashing waves, a different language, a troubled history, famous visitors, huge skies, machair, sheep, songs – the Hebrides are utterly distinct, and the ships that serve them have a fascination denied to more humdrum forms of transport. The ferries provide what the Scottish government likes to call ‘essential lifeline services’, adding a touch of drama to the most ordinary voyage, the two or three minutes it takes to cross the Kyles of Bute, for instance. More urgent lifelines, those that save islanders from death by heart attack or car crash, whir overhead on their way to helipads at hospitals in Glasgow and Inverness.

The delays and cancellations in the ferry services to the islands over the past few years are unprecedented in living memory. Covid and the extremes of climate change are partly to blame. The smell of British ineptitude, managerial and technical, also hangs about. Local people are often bemused by the ignorant mistakes made by officialdom. New piers turn out to be badly sited in terms of the prevailing wind and easy docking; breakdowns of onshore equipment – passenger gangways and the like – take months to fix. But rising above all this is the spectre of the long delayed ferries, whose absence has required older ships to continue sailing long beyond their life expectancy, which means that they are often tucked away in dry docks under repair. Tourism and island industries of all kinds have suffered. Not for the first time, island people accuse the ferries of ruining the local economy and despise MacBrayne’s as a tyrannical monopoly.

Before ships have names, they have numbers. The most famous number in Clyde shipbuilding, probably in shipbuilding anywhere, was the massive hull known to its builders, John Brown of Clydebank, as 534. Its keel was laid down in December 1930, just before the full force of the Great Depression hit Britain. Cunard Line, which commissioned the ship, ran out of money, and work on 534 came to a halt exactly a year after it began. Thousands of workers were laid off in Glasgow and in many other British towns and cities where parts were being made for the vessel, ranging from giant bronze propellers to ashtrays. Two years of uncertainty and political debate followed, during which 534 lay silent on the stocks and colonies of rooks and starlings nested in its rusting bulk, until the government at last agreed loans that would pay for the ship’s completion. Work started again on 3 April 1934, a date that on the Clyde came to symbolise the end of the Depression, and in September Queen Mary came north to launch the ship and name it after herself.

A million people are said to have lined the banks of the Clyde to watch the Queen Mary sail down the river on its maiden voyage in 1936. Ships often brought out the rhapsodic and the tribal in writers, as well as the informational (tonnage, length, speed, the decoration of cocktail bars). ‘That men should be able to create so largely and beautifully is in the order of poetry,’ the Greenock-born journalist and novelist George Blake wrote. ‘The pride of a seafaring nation and of a shipbuilding race were utterly engaged. This mass of metal had become the symbol of national self-respect. To leave her unfinished would have been as unthinkable as, shall we say, to scuttle half the fleet.’

This year, national self-respect didn’t seem to be at stake in Port Glasgow, though residents who knew the history of the town were saddened that it should be the scene of such a prominent failure. The ferries were by now familiar features of the townscape, their hull numbers almost as well known as 534 had been ninety years before. Hull 801, launched as the Glen Sannox in November 2017, had been lying at Ferguson’s fitting-out quay for nearly five years, while the bulbous and rusty bow of hull 802 had loomed above the shipyard’s entrance gates for almost as long. If the terms of the contract had been met, both vessels would have been at sea since 2018, hull 801 on the run from Ardrossan to Brodick on Arran, hull 802 working the so-called ‘Uig triangle’, from Uig on Skye to the islands of Harris and North Uist. The ferries were part of the Scottish government’s plan to reduce the average age of the ten largest vessels in the CalMac fleet (which has thirty ships in total) from 21 years in 2017 to 12 years by 2025, and thus to improve reliability, increase capacity and reduce carbon emissions and fuel costs.

By the historic standards of Clyde and Hebridean ferries, they are big ships, at 102 metres long the biggest ever built by Ferguson’s, and, barring the Loch Seaforth, which serves the Ullapool-Stornoway route, bigger than anything in CalMac’s present fleet. Their intended capacity is 1000 passengers and 127 cars or 16 HGVs. To reduce air pollution, their dual-fuel propulsion system by the Finnish firm Wärtsilä can use liquefied natural gas, LNG, as well as marine diesel (though the benefits of LNG are now less certain than they were when the ships were planned). Their paintwork, with the usual CalMac white superstructure above a black hull, dips in a curve towards the stern, aiming to give an impression of speed, power and modernity. A century ago liners sometimes had an unnecessary third or fourth funnel to achieve the same effect.

The Comet was built only a short walk from Ferguson’s, on land once covered in scaffolding, cranes and slipways and now occupied by Tesco, M&S, B&Q, Superdrug and TK Maxx. Several famous ships first touched the sea from this ground, including a trio that left their mark on maritime literature: the Narcissus, which had Joseph Conrad as its second mate; the Grace Harwar, which took Alan Villiers round Cape Horn; the Moshulu, up whose rigging the 19-year-old Eric Newby climbed on the last grain race from Australia. All were three or four-masted barques: one or two Port Glasgow yards specialised in this last generation of big sailing ships and went on building them into the 20th century. None has a memorial here. What survives is a battered full-scale replica of the Comet, made in 1962 to celebrate its 150th anniversary and now pitifully neglected. Holes have been punched through its wooden hull; its funnel, as tall, black and thin as a drainpipe, has been cut down and lies alongside on the ground.

In the popular version of Scottish history that once flourished in pubs and school playgrounds, Henry Bell invented steam navigation when the Comet began its regular voyages between Glasgow, Greenock and Helensburgh in the summer of Napoleon’s advance on Moscow. In fact, Robert Fulton’s steamboat Clermont had started running on the Hudson in 1807, and in the five years before Bell got going on the Clyde half a dozen other steamers had begun to carry freight and passengers on the Delaware, the St Lawrence, the Mississippi and Lake Champlain. Scotland’s great contribution came from the engineer William Symington, whose paddle steamer Charlotte Dundas, built in 1801, was a mechanical triumph let down in the end by his nervous backers (though it encouraged the later schemes of Fulton and Bell). Compared with Symington, Bell was the lesser engineer and the greater enthusiast, the better talker and the bolder fibber.

Hoping to combine public interest in two relatively new phenomena, steam navigation and sea bathing, Bell commissioned the Comet partly to convey customers to his hotel at the new seaside resort of Helensburgh, saving them a slow journey by river or an uncomfortable one by road from Glasgow. Bell had the idea and enthusiasm, but the ship itself was realised by others. In Glasgow, John Robertson made the engine and David Napier the boiler, while John Wood in Port Glasgow built the wooden hull and installed the machinery. The result was a marvel, the prototype of a steamer fleet that would revolutionise travel on the Clyde by 1820, when two dozen of them sailed every day except Sunday to previously hard to reach corners of the firth. London had its first sight of a steamboat when a Clyde-built ship (the Margery, launched in Dumbarton) arrived on the Thames in 1815; the next year it became the first to cross the English Channel and the first to be seen in Paris, where an excited crowd watched it from the Tuileries. In the face of more powerful marine engines, larger ships and fiercer competition, Bell began to look for new routes for the Comet – and found them in 1819 when the ship began a new service from Glasgow to Fort William in the West Highlands, avoiding the treacherous Mull of Kintyre by using the Crinan Canal, which opened in 1801, to cross the Kintyre peninsula. No steamboat had ventured west and north of Kintyre before: the population was small, impoverished and thinly spread, the seas could be rough and shelter hard to find. Where was the profit in it? Bell took a harsh view of Highland landlordism and believed in the civilising mission of steam navigation. ‘You landed Gentlemen owt to do a grate deal more than you dow in forming improvements in your Ilands and coast of the Highlands,’ he wrote to one laird. They were too taken up with ‘politicks, gamblin and other trifling amusements’.

The weather soon got the better of the Comet, which lasted little more than a year on the Fort William run before it was wrecked in a snowstorm off the west coast of Kintyre. But by the late 1820s at least six steamboats were sailing regularly from the Clyde to Oban and Fort William and the islands of Mull, Skye, Lewis and Staffa, where Fingal’s Cave had been attracting visitors by sailing boat since the mid-18th century: the list included Joseph Banks, Samuel Johnson and John Keats. Mendelssohn was an early visitor by steamboat (‘He is on better terms with the sea as a musician than as an individual or a stomach,’ his companion wrote of Mendelssohn on that choppy August day in 1829). Turner, Wordsworth and Jules Verne followed. Tourists inspired by the Romantic movement and the novels of Walter Scott began to make an important contribution to steamboat revenues, though, as the marine historian Andrew Clark notes, ‘it was the enthusiastically reported visit of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in 1847 that glamorised and popularised the West Highlands for the wider world, opening up the region’s commercial potential for keen-eyed entrepreneurs.’*

Among them were the brothers James and George Burns, Glasgow merchants turned shipowners who by the mid-19th century had become Scotland’s most powerful shipping magnates, with a network of routes around the coasts of Britain and Ireland and a large stake in transatlantic trade as founding partners of the Cunard Line. In 1851 they sold the Hebridean services to another pair of Glasgow brothers, the Hutchesons, but not before installing their nephew, David MacBrayne, a typefounder to trade, as a junior partner in the Hutchesons’ company; in 1879, after they retired, he renamed it David MacBrayne & Co.

By the turn of the century, no name in the Highlands was better known. ‘So interwoven with the romance of the Highlands are the red-funnelled steamers of Messrs David MacBrayne,’ the Inverness Courier wrote in 1905, ‘that if their decks could but tell what as sentient things they would have witnessed – all they have known of joy and sorrow, love and hate, of tragedy and comedy, success and failure – theirs were a tale worth the telling.’ Few other transport companies have become so entwined in the image of the places they served – the Irrawaddy Flotilla with imperial Burma, perhaps, or the Great Western Railway with Devon seaside resorts – and none over so long a period. Partly this is the achievement of the company’s striking publicity. MacBrayne and the Hutchesons before him milked Queen Victoria’s tour in 1847 to claim Scotland’s west coast as scenery fit for a queen, and inaugurated what advertisers called the Royal Route, a day-long voyage from Glasgow to Oban that broke the journey into three stages using three boats: the first took travellers down the Clyde as far as the entrance to the Crinan Canal; the second, an elegant little steamer, took them through the canal; a third waited at the other end to complete the journey through an island-dotted sea to Oban, where other MacBrayne ships might be taken for ports further north and west, or even north and east via the Caledonian Canal to Inverness. MacBrayne’s took tourism as seriously as any present-day holiday company. It published colourful booklets that described points of interest; it acquired Highland hotels; and it took a lease on Staffa to shut out competition in the Fingal’s Cave trade.

The ships were attractions in themselves. From the 1850s to the 1870s, they became swifter and lovelier, a progress that culminated with the launch of the flagship Columba in 1878. Named after the Irish missionary who landed on Iona in the sixth century, the Columba served the Clyde leg of the Royal Route for 57 summers (lesser ships were substituted out of season). At 301 feet long it was the largest steamer in the British coastal trade, and among the fastest at 17-18 knots (20 mph). The first coastal steamer to be made of steel rather than wood or iron, the Columba was also unusually light. Black smoke streaming from its twin funnels, its canoe bow running knife-like through the waves, the ship became a famous sight all along its route. Those lucky enough to be aboard (Glasgow merchants, Edinburgh solicitors, the London owners of Highland estates) enjoyed magnificent breakfasts and lunches in the dining saloon, shopped at stalls selling books and fruit, sent postcards from the ship’s post office and had their beards trimmed at the onboard barber’s. The Columba went to the breaker’s yard in 1935 and seventy years later people who had seen it as children, from a riverside tenement or an Argyllshire beach, still talked of it as something grand and unforgettable.

Profits from the summer trade helped subsidise the less glamorous routes that carried freight and livestock, as well as passengers, to remote places all year round. At first this worked well enough: summer’s profits balanced winter’s losses. But summer revenues began to dip in the Edwardian period, the start of a long decline marked by two world wars and the coming of the car, the bus and the plane. There was a limit to the fares that MacBrayne’s could charge a working population of crofters, fishermen, priests and Free Church ministers. To add to this seasonal imbalance there was (and is) what Clark identifies in his superb company history of MacBrayne’s as ‘the equally huge adverse balance between what the Highlands and Islands produce and what they consume’. Small communities sucked in produce from the mainland – at one point almost every loaf of bread sold in the Hebrides was baked far away in Glasgow – and returned almost nothing by way of cargo. Slowly, often against its will, the state found a role. The first state subsidies came in the form of Post Office contracts to carry the Royal Mail – giving MacBrayne’s a near monopoly of seaborne mail along Scotland’s west coast. In 1890 a government report into the troubled economy of the Highlands and Islands proposed an expansion of sea services, allowing MacBrayne’s to reap more subsidy and gather a local reputation, which has never left it, as an oppressive monopolist feather-bedded by government funds: in Clark’s words, ‘a profiteer from the big city who rode roughshod over poor communities’. During the First World War the summer traffic more or less vanished and the price of fuel – steam coal was badly needed by the Royal Navy – rose steeply: facing large losses, the company begged for more money ‘otherwise the Mail services will automatically cease’. Soon there was talk of a government takeover, which was eventually ruled out on the grounds, to quote an official in the Scottish Office, that ‘we must be careful not to assume too much responsibility for this service’; the government should be wary of taking on the blame presently shouldered by a private company.

Complaints came from landowners with political influence as well as crofters with none. In 1919 the factor to Lord Leverhulme, who was on the verge of buying Harris, wrote that for seven weeks from January to March no cargo at all had been landed from Glasgow, with the result that for the last ten days of that time there had been no food in the local shops: ‘the people were without butter or margarine, no sugar, no bacon … The whole position is really becoming quite intolerable … If the government have got the interests of the people at heart, they must begin with the steamer question and reorganise the whole service.’ In the same year the people of Loch Skipport in South Uist complained that a community whose ‘sons and brothers have had to face the hunnish foe in a foreign land for King and Country, should be so exploited by rapacious Steamer Companies’.

Some of the complaints were reasonable, others less so. The island of Colonsay had nine sailings to and from the mainland every month, when the steamer called on its journey between Glasgow and the Outer Hebrides. In 1931, Colonsay had a population of 232 and the government estimated the average traffic per trip totalled half a dozen passengers and a few dozen boxes of rabbits and lobsters. Nevertheless, Colonsay’s owner, Lord Strathcona, a former Tory minister, consistently agitated for more steamer calls. John Lorne Campbell, described by Andrew Clark as ‘the ever-whining proprietor of Canna’, more often remembered as a historian and folklorist, was outraged when MacBrayne’s substituted a smaller boat on the service to the Small Isles. Mallaig, the mainland port, was only two and half hours away and Canna’s population was 24, but Campbell felt they deserved the cabins and the full catering service offered by the previous vessel. The mollifying response, Clark writes, ‘was the provision of soup’.

The company limped on through the 1920s with an ageing fleet – replacements were unaffordable – until in 1927, MacBrayne’s annus horribilis, two of its ships ran aground and another caught fire. All three were written off as total losses. The next year, when MacBrayne’s had to renew its mail contract, the criticism was savage and unrestrained: everything wrong with the Highlands and Islands, the age-old litany of depopulation, depression, economic failure and poverty, was laid at its door. In a letter to the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, the Tory MP for Argyllshire, F.A. Macquisten, made unfavourable comparisons with Norway’s coastal services (the same comparison, just as unfavourable, is still being made) and proposed that an efficient railway company took over the fleet. In the subsequent parliamentary debate over the renewal of the mail contract, the radical Labour MP Tom Johnston argued that there was ‘no justification whatsoever for allowing this private company, subsidised by the government, to retain control over these essential means of communication … Today we have an opportunity of breaking one of the cords that are slowly strangling the [Highland] race.’ The question of the contract went down ‘to the roots of the evil which besets the islands of Scotland,’ one MP said, while another added that the fleet was on average 68 and a half years old (untrue; though its most elderly member, the Glencoe, had survived since 1846 and was thought to have been the oldest working steamship in the world when it was withdrawn in 1931). David Kirkwood, a Red Clydesider like Johnston, denounced the company as ‘this petty little firm on the Clyde … ruining one of the most beautiful parts of the world, the Highlands of Scotland’. The Highlands could be ‘opened up’, he said, if the government took this ‘glorious opportunity’.

In the face of this onslaught, Hope MacBrayne, the founder’s son, threw in the towel. He abandoned his efforts to have the mail contract renewed and in 1928 sold the company for £75,000 to a consortium put together with government help. The new firm kept the old name, David MacBrayne, though no member of the MacBrayne family had any connection to it. According to a piece of sly Highland satire inspired by the 24th Psalm, ‘Unto the Lord belongs the Earth/And all that it contains/Except the Kyles and Western Isles/For they belong to MacBrayne’s.’ But to whom did MacBrayne’s belong? The new consortium’s capital was divided equally between the London, Midland and Scottish railway and Britain’s largest coastal shipping company, Coast Lines, both headquartered in England. But though (or because) the ownership of the little ships with their red and black funnels went south, the company’s image became more Scottish than before. All new-built ships were named after lochs, saltires and lions rampant emblazoned the posters, and the silhouette of a kilted Highlander wielding a targe and a raised claymore was adopted as the company symbol.

The takeover was a lifesaver for MacBrayne’s. A sympathetic government fixed an annual subsidy of £50,000 for the next ten years; the company immediately cut freight rates by 10 per cent and ordered four new vessels. Several more arrived before the Second World War. However distant the new ownership, it gave the company a future. But MacBrayne’s heyday, like so much else in Scottish life, belonged to the late Victorian and Edwardian age. That the name still survives today is remarkable given its inglorious end as an independent company, and Scotland’s history of extinctions over the past century. Lipton’s the grocers, the Scottish Co-operative Wholesale Society, North British Loco, Keiller’s marmalade, the Great North of Scotland Railway, the Dunfermline Linen Warehouse: where are they now? But there is MacBrayne, bolder than ever on the sides of its ships, its Scottishness underscored by the adjective Caledonian, as enduring in its patriotic appeal as a Tunnock’s Teacake.

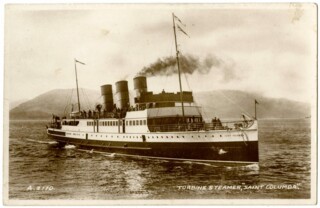

Soon after I saw Ferguson’s shipyard on that summer’s day in 1955, I went with my uncle, aunt and cousins to the promenade in Gourock. It was a Saturday afternoon; my uncle worked in the drawing office at Kincaid’s marine engine factory, where the week ended on a Saturday lunchtime. Gourock stands at the point on the Clyde where the estuary broadens out and takes a sharp turn to the south: the views west across the firth to the Cowal hills are celebrated, particularly for their sunsets. Into this view came an astonishing sight: what seemed to be a miniaturised version of an Atlantic liner, an elegant little ship with not one or two but three funnels, all nicely raked and painted red and black. This turned out to be St Columba, a pre-1914 turbine steamer to which MacBrayne’s had added a third funnel, a dummy, perhaps to perpetuate the prestige of the Royal Route (where it had replaced the old Columba) as well as to pay homage to the Queen Mary, another three funneller but a hundred times heavier.

In 1955 nothing much had changed since 1935: travellers took trains to the railheads at Gourock, Oban, Mallaig and Kyle of Lochalsh and then carried their suitcases up wooden gangways to steamers (as the ferries were still called) that had stewards and dining saloons. A steamer would slow to a halt far from the shore, to be met by a flit boat waiting to load or unload a passenger or two, or a ewe or a ram. Skye was the only island with stretches of two-way road. Elsewhere, drivers made do with single track roads and passing places. Mull, twice the size of the Isle of Wight, had two hundred cars. To ship a car there, or to any island other than Skye, was a complicated process involving the use of a crane or planks laid in parallel at the right state of tide from the quay to the ship. Few cars crossed to the islands until the mid-1960s, when the government, which as a result of railway nationalisation now owned half of MacBrayne’s, funded three car ferries and leased them to the company. The results were startling – in five months in 1964 MacBrayne’s carried five times as many vehicles to Mull as during the whole of 1963 – but the government’s direct involvement in the ships’ financing ran contrary to the traditional philosophy that subsidy was always to be preferred to ownership. As a Transport Ministry memo put it, subsidy ‘can be more easily restricted under contract with a private firm than [with] a nationalised undertaking, upon which the strongest possible [public] pressure would be exerted to maintain a standard of service higher than that at present in operation’.

MacBrayne’s received 300 per cent more public funding in 1949 than it had ten years earlier, while revenue only rose by 100 per cent. Over the next twenty years the gap went on growing, to renewed criticism that the government was subsidising a complacent private monopoly that paid little attention to local needs. By the late 1960s, public ownership could no longer be avoided. In 1969, the Labour government’s new Scottish Transport Group bought out the half of MacBrayne’s shareholding still held by Coast Lines, and in 1971 began the process of merging MacBrayne with the Caledonian Steam Packet Company, founded in the late 19th century by the Caledonian Railway to operate a fleet of steamers on the Clyde, its name somehow surviving the death of its parent fifty years before.

The promised efficiency savings failed to materialise, however, and the subsidies continued to swell. Between 1972 and 1982, an inflationary decade, they multiplied by a factor of five. But the company could argue that the money wasn’t being wasted. When responsibility passed from Westminster to the new Scottish government in 1999, Caledonian MacBrayne owned thirty vessels with an average age of 15.4 years – the lowest in MacBrayne’s history – and ran services that were cheaper, more frequent and more reliable than they had ever been. The company’s methods of procurement and subsidy, however, conflicted with EU competition law. A Brussels directive obliged it to put out to competitive tender any contract worth more than €150,000; as a result, orders for two medium and two large ferries went to Poland and Germany rather than British yards at a time when Ferguson’s still had the capacity and workforce to build them. The EU law on state aid – that it must not distort competition – had more complex results. To comply with the rules, the Scottish government had to devise a tendering process for the shipping services on the Clyde and the Hebrides that MacBrayne’s had considered its own. When the government published its consultation document there was widespread public alarm that the best routes would be cherrypicked – best in terms of subsidy; few if any routes made a profit – while others went to the wall or made do with inferior vessels. So the government proposed instead to invite tenders for the Clyde and Hebridean ferry services as a single operational unit. To reassure Brussels that this wasn’t merely a trick to perpetuate the old order, it came up with a plan to separate the infrastructure from the service, rather as the railway privatisation of the 1990s created a company, Railtrack, that took care of the rails, the civil engineering and the signalling, while the variously subsidised train operating companies won access to these assets by winning a franchise.

The infrastructure in MacBrayne’s case comprised the ferries themselves and about half of the piers and terminals they used – local authorities owned the others. In 2006 these became the property of a new publicly owned company, Caledonian Maritime Assets Ltd (CMAL), which leased the fleet at commercial rates to a new operating company, CalMac Ferries Ltd (CFL). CFL was a subsidiary of another publicly owned company, David MacBrayne Ltd, which had one or two assets elsewhere in the UK. An offshore company, Caledonian MacBrayne (Crewing) Guernsey Ltd, was established at the same time so that CFL could avoid paying the employer’s share of National Insurance contributions. All these bodies were answerable to a new government agency, Transport Scotland, which in turn answered to government ministers.

Under these convoluted arrangements, CFL won the franchise unopposed when it was first awarded in 2007, but when in 2015 it bid £900 million for another eight years, it found a rival in the ubiquitous outsourcing agency Serco, which in 2012 had won a similar franchise to run the shipping services to Orkney and Shetland. Trade union leaders, the political opposition and community campaigners were outraged, fearing that the government was prepared to privatise the ferry service, threatening the crews’ pay, pension rights and working conditions. The Rail, Maritime and Transport union (RMT) went on strike for a day; journalists (including me) fretted about the end of a company that had, in the words of one columnist, ‘carved itself an enduring place in the nation’s affections’. Among its opponents, Serco was a byword for hard-nosed profiteering from government contracts. By repositioning itself as firmly left of centre, the SNP had swept Labour from its heartlands in the West of Scotland in the 2015 general election and established itself as old Labour’s ideological heir. It could hardly go against a campaign based on fine Scottish traditions and working-class rights. The first minister, Nicola Sturgeon, announced that CalMac had retained the contract. ‘CalMac have a long and proud tradition of running the Clyde and Hebrides routes,’ she said, ‘and the company is woven into the fabric of the communities they serve.’

She didn’t mention, and too few of us understood, that Caledonian MacBrayne and CalMac Ferries Ltd were different things. The second ran the ferries, the first was a dormant limited company whose intellectual property rights were owned by CMAL. In other words, Caledonian MacBrayne was a brand: it could be sold. The sudden rush of sentiment – that the dear old name might be evicted from its Highland home – was misplaced. The name and the livery could remain, whoever operated the ships: Serco or the sovereign wealth fund of Dubai. No traditions were imperilled, but jobs were at stake. Since the Scottish government decided on the routes, the levels of service and the subsidy, a new franchise-holder had little room to find a profit by cutting costs, other than in the size of the crews and their wages and conditions.

The ferries were busier than they had ever been, thanks to a decision by the Scottish government to implement the Road Equivalent Tariff (RET), which used a formula linking ferry fares to the cost of road transport over an equivalent distance. RET has its origins in the ferries that cross the Norwegian fjords and was first mooted in Scotland in the 1960s by the Highlands and Islands Development Board (HIDB), originally, Clark writes, ‘to neutralise decades of islander complaints about MacBrayne’s freight charges’, and later and more broadly to make the islands cheaper to access, and in that way to level up the economic gap between island and mainland living. The HIDB formally proposed the scheme to the Westminster government in 1974, to have it rejected by successive UK administrations, Tory and Labour, for the next 25 years. RET-based fares would cover only a quarter of the operating cost. The Scottish Office minister Bruce Millan reflected conventional political opinion when he argued in 1975 that the fares needed to be anchored in some economic reality or the subsidies would be uncontrollable.

After power was devolved to Holyrood, outright rejection carried a greater political cost. In the run-up to the Scottish elections in 2007, Labour promised to discount ferry fares for islanders by 40 per cent; when the SNP won, it went further. After a four-year pilot scheme in which fares to some islands were cut by up to 50 per cent, RET was rolled out across the entire system. The reductions were astonishing, especially for vehicles, and applied to everyone who travelled, not just islanders. RET cut the cost of taking a car from Oban to Colonsay and back from £146 to £70; on the Clyde the return fare to Arran dropped from £82 to £30.20.† According to Scottish government figures, average cuts in passenger fares of 44 per cent and in car fares of 55 per cent in the first ten years produced on average 20 per cent more passengers and 31 per cent more cars – with a 125 per cent increase in motorhomes, which soon became some of the most loathed objects in the Hebrides. They took up deck space, they crowded single track roads, they left refuse and human waste behind; and by importing most of their food and drink from mainland supermarkets and not staying in hotels or holiday cottages their owners contributed almost nothing to the local economy.

RET had other unintended consequences. In the summer, islanders sometimes found it impossible to find room on ferries packed out with tourist cars. There was talk of ‘over-tourism’ and damage to fragile island ecologies. The figures suggested that passengers who had once travelled without cars now took them. By 2017, the annual total for cars and passengers reached 1.4 million and 5.2 million respectively: increases of 37 and 17 per cent over the average for the previous five years. CalMac had never been busier, and yet – a paradox produced by RET – it had never depended more on public funds. Between 2007-8 and 2016-17, the annual subsidy had nearly tripled, from £57 million to £144.2 million, while the contribution of fare revenue to operating costs dropped from 53 to 29 per cent. The Scottish government refused to identify deficits and subsidies on a route by route basis. Informed calculation, however, produced a startling picture. In April 2010, the Oban Times reported that out of 9469 sailings the previous December, 800 had failed to carry a single passenger, while another 3075 had carried five or fewer. Three years later, the writer and shipping consultant Roy Pedersen, one of CalMac’s sternest critics, estimated that the ferry to the Small Isles (Rum, Eigg, Canna and Muck, whose population at the 2011 census totalled 153) cost £26,000 a year for every man, woman and child who lived there. CalMac could respond only that it had to meet contractual obligations set by the government: it had no flexibility. It couldn’t regulate traffic by increasing fares on popular routes or reducing sailings on less lucrative ones.

In 2008, the Scottish government, then a Labour-Lib Dem coalition, established a Scottish Ferries Review to examine current services and propose improvements. As well as officials from CalMac and CMAL its panel included civil servants, academics and consultants, and for four years it held public consultations and gathered evidence, and then drafted and redrafted a plan for ferry services covering the ten years from 2012. The fundamental conundrum of the Scottish government’s Hebridean transport policy waited to be addressed. Was CalMac an inherently social enterprise, funded by the state so that isolated communities such as the Small Isles could survive and even prosper? Or did it need it to behave more like a commercial business with a strictly limited access to public subsidy? In Clark’s formulation, ‘how does a nation with finite resources set a limit on its obligation to support tiny outlying communities, where traffic is often negligible, the weather poses dangers to shipping, and public expenditure per head of population greatly exceeds the rest of the country?’ The question was never explored. Instead, the Ferries Review offered a few practical recommendations – that the fleet reduce carbon emissions using new technologies; and that eight ageing ferries be replaced before 2022, otherwise by that date a third of the fleet would exceed the thirty-year age limit prescribed in the plan.

Three small ferries using a combination of diesel electric engines and lithium ion batteries were already on order from Ferguson’s of Port Glasgow, but the shipyard had little other work. In 2012, the order for a new vessel for the Ullapool-Stornoway route had gone to a shipbuilder in Flensburg in Germany. With a length of 117.9 metres, the Loch Seaforth was the biggest ship ever to sail under the flag of CalMac or its predecessors. Size had begun to matter. With the surge in traffic generated by RET, the service needed capacity as well as renewal. Bigger ships were an obvious answer (though some of CalMac’s increasingly vocal critics, such as Pedersen, thought that a bigger fleet of smaller ships, to increase frequency as well as capacity, might be a better one).

The 2012 Ferries Plan proposed two large new ferries for the Clyde and Hebridean network, and in 2013 CMAL, Transport Scotland and CalMac began to develop plans for the dual-fuel ferries that were to become hulls 801 and 802. CalMac gave CMAL a Statement of Requirements – what it wanted in terms of capacity, speed, manoeuvrability and so on – which CMAL tested for feasibility and then developed into a preliminary or ‘conceptual’ design. Transport Scotland, which was funding the vessels via a loan to CMAL, estimated the cost at £40 million for each ship, reduced by 10 per cent to a total of £72 million if both were built at the same time. In October 2014, CMAL published a contract notice on the Scottish government website setting out what it expected in terms of design, construction and delivery dates, and stipulating the requirements potential bidders needed to meet. None of these was at all unusual, and they included the condition, standard to shipbuilding practice, that the bidder provided a Builder’s Refund Guarantee or BRG.

In December 2014, CMAL issued an invitation to tender to a shortlist of potential bidders, setting out its requirements in 135 pages of technical specifications and including a draft of the contract a successful bidder would be expected to sign. Devised by the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) and used throughout the shipbuilding industry, this was a ‘design and build’ contract under which the shipyard undertakes to design and build a vessel to the buyer’s specification at a fixed price, with the full risk remaining with the builder throughout the construction period. According to a later report by Audit Scotland, which audits the Scottish government and other public organisations

the BRG is an integral part of the BIMCO contract and is the main source of financial security for a ship buyer. Typically, it is an agreement between the shipbuilder … and a bank to refund 100 per cent of the payments to the buyer … if it cancels the contract (because, for example, the ship does not meet the specification, is late, or if the shipbuilder is deemed insolvent). With a 100 per cent refund guarantee in place, the full financial risk of the project rests with the shipbuilder.

By the deadline for submissions, 31 March 2015, CMAL had received seven bids from six shipbuilders: one in Poland, another in Turkey, two in Germany, one in England (Cammell Laird at Birkenhead) and one in Scotland: Ferguson Marine Engineering Ltd in Port Glasgow. Even a year earlier the last bid would have seemed wildly improbable. In 2005, a meeting of the Scottish cabinet had decided the yard’s decline was ‘close to irreversible’, and for nearly a decade its workforce had dwindled until it could be counted in dozens. Orders failed to materialise. Skilled staff went elsewhere. Some workers found jobs in the warship yard of BAE Systems upriver or were bussed across Scotland to Rosyth in Fife, where Babcock were building two aircraft carriers.

On 15 August 2014, Ferguson’s fired its last seventy employees and entered administration. Only a year later, on 31 August 2015, the Scottish government announced the yard as the preferred bidder for a two-vessel contract that was now worth £48.5 million for each ship (with another £3 million allowed for any adjustments CMAL might require during their construction). It was the most expensive tender submitted, but CMAL judged it the best value overall, when cost was combined with quality.

This marvellous change in fortune had two enablers: the Scottish government and the Scottish businessman Jim McColl, who with government encouragement bought Ferguson’s for £600,000 the month after it went bust. Ferguson Shipbuilders became Ferguson Marine Engineering Ltd (FMEL), and was soon hiring staff and building new offices and workshops. Many things were propitious. McColl was a rare survival, a bright Scottish industrialist who had begun his career as an engineering apprentice in Glasgow and made a huge amount of money from manufacturing (the Sunday Times Rich List in 2022 estimated his fortune at £996 million). He was on friendly terms with senior figures in the SNP such as John Swinney and Alex Salmond, who was still first minister when McColl’s interest in Ferguson’s began. Of course, orders would have to be won through open competition, but in a country with an enduring demand for small ships – as ferries and as service boats for the big offshore industries: oil rigs, wind turbines and fish farms – there would be plenty to bid for. Finally, there would be no question of remote foreign owners misreading local conditions or being too quick to pull out. The shipyard’s offices lay only a ten-minute walk from those of what promised to be one of its principal customers, CMAL, which had established itself on the upper floor of Port Glasgow’s fine neoclassical Town Buildings (abandoned as the site of municipal government in the 1970s, when Gourock, Greenock and Port Glasgow become a single local authority, Inverclyde). Several people – draughtsmen and engineers – had moved from Ferguson’s to CMAL and still kept in touch with people in the yard. Port Glasgow is a small and talkative town. When trouble started, there would be no question of confining bad news to those with a need to know it.

But that came later. In 2015, the news was good. Travelling by train through Port Glasgow, I would look out at its familiar landmarks: the abandoned tenements, the long-closed ropeworks where my cousin Margaret used to work, the near derelict hotel where in 1964 I danced at her wedding. Among these dim memorials, how could a reinvigorated shipyard with an ambitious industrialist at its helm be anything other than cheering?

The son of a butcher, Jim McColl was born in 1951 in a village just outside Glasgow, and left school at sixteen to start a four-year apprenticeship at Weir Pumps, one of the city’s last big engineering firms. At Weir’s he showed unusual ambition. City & Guilds and Higher National certificates were followed by full-time study for a BSc and then, back at Weir’s, by an MBA achieved via evening and day-release classes. In 1981, he took a management job in an engineering company that supplied equipment to power stations and studied part-time for a degree in international accounting and finance. The accountants Coopers and Lybrand headhunted him to work with companies in financial trouble and turn them round. After several successes, latterly as an independent consultant, he spent £1 million on a 29.9 per cent stake in a Clydebank engineering firm, Clyde Blowers plc, and with the help of a management buy-out took the company private.

Like Weir Pumps, Clyde Blowers had its origins in steam technology. It manufactured a device that could blow soot from the boilers of steam engines – in locomotives, ships, factories and power stations – without the boilers having to be shut down. The ship or the factory could continue, the flow of steam to its engines unaffected. ‘Most of the Clyde-built ships had Clyde Blowers in them, including the royal yacht Britannia,’ McColl told me when I spoke to him in May, although by the time he bought the company its focus had shifted to coal-fired power stations. In 1992, it was the smallest of eight similar firms scattered across the world. In the following five years, McColl bought six of the other seven. ‘We ended up with 60 per cent of the world market and that included a very big market in China, where we set up a very successful factory,’ he said. ‘When I bought Clyde Blowers we were making 600 soot blowers a year. When we sold the Chinese factory, it was doing 6000 a month.’

The sale of the Chinese factory reflected a change in the company’s direction: ‘Coal was going out of favour, so we started investing in other businesses.’ One of these was Weir Pumps, where McColl had started his career forty years before; that company, too, was reshaped and sold on. Today McColl is the chief executive of Clyde Blowers Capital, which describes itself as ‘an independent investment firm based in Glasgow … managing more than a hundred companies spanning six continents, over five thousand employees, and revenues in excess of £1 billion.’

McColl told me he was drawn to the shipyard because of ‘the fantastic history of shipbuilding we had in Glasgow’, and, though an unlikely sentimentalist, he may have been sincere. Reviving the yard appealed to him as an engineer; perhaps it would also allow him to show what he could do as an industrial leader. Shipbuilding had collapsed through want of leadership, he said. ‘The unions get blamed for it, but I didn’t think it was the unions that were the problem – it was lack of change, lack of the management of change by the leadership of the industry.’ And Ferguson’s didn’t look a bad proposition. ‘I did a lot of work on the market opportunity and what [orders] might be available to a small niche yard and I found that there was plenty of work about and there was no reason why that yard shouldn’t be successful. But it was like walking back into the 1920s when you went into the yard. I mean, it was dire. Underinvestment on a huge scale.’

His account omitted the politics. McColl had been nudged towards Ferguson’s by the SNP leadership. As he told the Scottish Parliament’s Public Audit Committee in June this year, ‘Whenever any issues came up with businesses that were in trouble, I always got a phone call from Alex Salmond asking me whether I would have a look at it or whether I would be interested in it.’ Usually, he had a look and said no. This time, ‘when Alex Salmond asked about the shipyard, we had a further look at it, did diligence on it and decided to go ahead with it.’ McColl added that it was ‘very much a working relationship’, stressing that he’d never given money to any political party and that ‘I try not to be a supporter.’ But when he bought the yard in August 2014, with the independence referendum only a month away, it was difficult to see him as anything else. He backed independence (‘I was naive about that,’ he told me) and had close connections to a range of SNP ministers. According to the audit committee’s convener, the list of people to whom he had easy access included the first minister; the deputy first minister; the cabinet secretary for finance, economy and fair work; the minister for business, fair work and skills; and all three transport ministers. McColl said he knew them through his membership of various pro bono organisations such as the Council of Economic Advisers, but civil servants in Edinburgh were aware that the relationship between McColl and the Scottish government might attract a darker speculation. In August 2015, with the government keen to announce Ferguson’s as the preferred bidder before the contract had been signed – as it turned out, the signing was several weeks away – an official in Transport Scotland considered the reaction of the other bidders. ‘As with any procurement, a legal challenge from one of the unsuccessful shipyards cannot be discounted,’ the official wrote (the name, as with many others in the documents released by the Scottish administration, has been redacted). ‘CMAL have not identified any particular risks in this regard and, in any case, are confident that any challenge can be defended. That said, the relationship between Scottish ministers and Ferguson’s owner is well known.’

Nicola Sturgeon, who had succeeded Salmond as first minister in N0vember 2014, came to Ferguson’s to announce the yard as the preferred bidder on 31 August 2015. The timing had political benefits. The Scottish government knew that the then chancellor, George Osborne, was to announce the UK government’s plans to spend £500 million on the expansion of the Royal Navy’s nuclear submarine base at Faslane, a few miles across the firth from Port Glasgow, on the same day. Thousands of jobs would be created, Osborne said. When it came to creating employment, Westminster could not be allowed sole bragging rights. The ferries deal, Sturgeon claimed, underlined ‘our commitment to creating the vital jobs needed to boost local economies and help stimulate growth across Scotland’. Similarly, it may not have been a coincidence that the contract for the ferries was formally awarded on 16 October, the day after the SNP’s annual conference began in Aberdeen.

When I spoke to him, McColl was keen to point to these as examples of the government ‘rushing … to get [things] out for PR reasons’. But the timing held important benefits for him, too. When he gave evidence to the audit committee seven years later, the convener, the Labour MSP Richard Leonard, suggested to McColl that the announcement of Ferguson’s as the preferred bidder ‘must have strengthened your hand in any negotiations that were taking place’. McColl disagreed: subsequent negotiations had taken longer than he had expected – they had, he implied, been difficult. Leonard pressed him:

The first minister – the head of the government and the leader of the Scottish National Party – comes along and announces Ferguson Marine as the preferred bidder. She would have been made to look pretty foolish, would she not, if five and a half weeks later it was decided to put the contract back out to tender? That must have strengthened any negotiations that you were having with CMAL about the Builder’s Refund Guarantee.

McColl: We had already agreed that before she made the announcement.

Leonard: You had agreed the Builder’s Refund Guarantee?

McColl: Yes.

But that was not the way CMAL understood the position; in fact, it wasn’t the position. McColl had never intended to comply with the requirement of a BRG, at least as it is normally understood, as a guarantee of a full refund by the builder of all the buyer’s costs should things go wrong. A BRG was among the mandatory requirements for bidders, although they could provide comments or amendments to the draft contract. Some of the bidders provided comments; FMEL didn’t. In the later view of the Audit Scotland report (published in March this year), the absence of comments from FMEL implied its acceptance of the contract’s conditions in full. CMAL first discovered this wasn’t the case five months after FMEL submitted its bid, and ten days before it was to be announced as the preferred bidder. The current interim chair of CMAL’s board, Morag McNeill, told the Public Audit Committee in June that CMAL had expected the refund guarantee to come from the shipyard’s parent company, Clyde Blowers Capital.

McNeill: We became aware that FMEL could not provide a Clyde Blowers Capital guarantee on 21 August 2015. We were not aware until about 25 September that it was also having problems producing a guarantee from a bank or an insurance company, and it gave its final position in relation to that on 7 October, by which time it was already the preferred bidder and we had stood down the other bidders.

Sharon Dowey [committee member and Conservative MSP]: When you found out that it was not going to give you the Builders Refund Guarantee, which was part of the tendering process, why did you not cancel the contract at that point and go back to the tendering process? In the communication that you have sent through, that seemed to be your preferred choice.

McNeill: That was indeed the preferred option.

Dowey: Why did it not happen?

McNeill: Because the minister authorised us to proceed.

McColl has a different version of this story. He had decided he couldn’t bid because the draft contract asked him to provide a BRG: shipbuilders in Germany, Poland and Finland have national investment banks that provide refund guarantees, but the UK has nothing similar. Clyde Blowers Capital (and its £1 billion turnover) was invested in several companies, he said, and couldn’t give guarantees for all of them. It would be against his fiduciary duty. ‘Again, it was £100 million. No one in their right mind will put up a guarantee like that,’ he told the audit committee. ‘That is why foreign competitors get the backing of a mechanism that is put in place by their governments.’

When the local MSP, Stuart McMillan of the SNP, was shown round the yard early in 2015, McColl explained to him why FMEL couldn’t bid for the contract. ‘He took that up with the Scottish government,’ McColl told the committee. ‘I am not sure who he took it up with, but the email that came back from Derek Mackay [the transport minister] effectively gave us the green light and said that we did not necessarily need to put up a cash refund guarantee, as something else could be negotiated. That is the message that we got back.’

The email was sent on 5 February 2015 from Mackay to McMillan, who then shared it with McColl. What McColl took for a green light was this passage:

While CMAL’s board, in line with standard industry practice, has a preference for refund guarantees it has on occasion taken alternative approaches to ensure that ship yards, including Ferguson under its previous owners, were not excluded from bidding for these government contracts … FMEL, and Jim McColl personally, have publicly stated their ambition with regard to these orders, and I am sure they will be seeking to put this ambition into effect.

I hope this reassures you [McMillan] that, in line with the 2012 Ferries Plan, the Scottish government is continuing in its commitment to vessel replacement and providing potential work for the shipbuilding industry in Scotland.

McMillan hasn’t disclosed the email that prompted this response, or the identity of its recipient; some reports suggest it was John Swinney, finance secretary and deputy first minister, who with Salmond had encouraged McColl to rescue Ferguson’s. The claim that CMAL had sometimes considered ‘alternative approaches’ to the guarantee is unverified; members of CMAL’s board denied it in their evidence to the audit committee. McColl, of course, may have received private and undocumented assurances from senior political figures. As the published evidence stands, however, he submitted a bid for a £100 million contract in the belief that one of its mandatory conditions could be ignored, on no stronger grounds than an email sent to someone else containing a brief statement about CMAL’s alleged past behaviour.

When CMAL’s board met on 21 August 2015 to choose FMEL as the preferred bidder, it knew nothing of Mackay’s message, and so the email that arrived from the lawyers of Clyde Blowers Capital early that evening came as a surprise: there would be no full refund guarantee, it said, from FMEL’s parent company. In the weeks of negotiation that followed other problems emerged, not least FMEL’s proposal that its final payment from CMAL should amount to only 0.5 per cent of the contract price. (Buyers pay shipbuilders in stages, according to the work completed; the final payment is usually large – 20 per cent is customary – to incentivise shipbuilders to deliver on time.) Feelings in CMAL ran strong. When on 31 August Sturgeon visited the yard and put on her white hard hat and high-viz jacket to announce FMEL’s triumph, it was against the advice of CMAL’s then chief executive, Tom Docherty, who warned Transport Scotland about the risks of excessive publicity. No member of CMAL’s board attended the event. ‘We were still in negotiations with our preferred bidder on a number of technical aspects as well as a number of issues on the contract,’ McNeill told the audit committee. ‘We were concerned that it would be seen as a fait accompli with the public, when we still had significant miles to go on the contract.’ CMAL’s chairman, Erik Østergaard, a Danish businessman with long experience in shipping, told the committee that ‘there were nearly two months of negotiations ahead of us, so we did not consider at that stage the contract negotiations to be completed at all.’ The negotiations lasted all through September. On 26 September, Østergaard replied to a note from Docherty:

It seems to me FMEL don’t get the point … The issue is that the level of refund guarantee is not sufficient. At present, the bulk of the possible engagement with a newly established shipyard with no track record at all of building ferries of this size, is an unsecured risk … equal to about £60m which is totally off the track of what is normal practice for the shipping industry … If FMEL don’t get back with substantially improved conditions … the board of CMAL have no other option than once again reject the deal.

FMEL’s final offer was a refund guarantee worth 25 per cent of the contract price; a final payment on delivery worth 25 per cent of the contract price; and a legal process known as ‘vesting’, by which all the material, equipment and machinery brought to the yard for a vessel’s construction becomes the property of the buyer rather than the builder. Kevin Hobbs, Docherty’s replacement as chief executive, told the audit committee that CMAL had emerged from the negotiations ‘happier than we were when we started off. Were we 100 per cent happy? Absolutely not.’

The board was well aware that the Scottish government wanted FMEL to have the contract. But CMAL’s interests were different. In terms of the Companies Act, the contract failed to protect the company’s interests. Østergaard needed someone or something else to share the risk, so he turned to CMAL’s sole shareholder, the Scottish government. Usually, the building of a ferry went ahead after CMAL, having concluded terms with the shipbuilder, recommended to Transport Scotland that the minister responsible should approve the award of the contract. Then Transport Scotland could loan CMAL the price of the contract – what CMAL would pay the shipbuilder – plus what the contract would cost it in terms of supervision and implementation: in this case, a grand total of £106 million, to be repaid over 25 years from the lease of the two vessels to CalMac. But this time CMAL wrote to Transport Scotland asking for a legal document that would safeguard its commercial and financial interests if the contract went wrong. This ‘letter of comfort’ was drafted by John Nicholls, an official at Transport Scotland, and addressed to Østergaard, whose fellow board member McNeill, a lawyer, had told Nicholls what it needed to contain. Its most important sentences read:

If any of the identified risks arises and … additional costs are incurred by CMAL then the Scottish ministers will look favourably on requests by CMAL for additional resources. I note in this context that the Scottish ministers intend for CMAL to receive sufficient funding for the company to continue to operate in accordance with its statutory obligations and contractual requirements … Funds will be provided as they are required in order for CMAL to meets its debts as they fall due and maintain the company as a going concern.

I confirm that the Scottish ministers have considered and approved the contents of this letter.

I would welcome confirmation from you, on behalf of the CMAL board, that you are content with the assurances of the Scottish ministers provided above.

Østergaard and his board were content. On 8 October 2015, an official (the name was redacted) attached the letter of comfort to an email to Mackay seeking his agreement to award the contract to FMEL and emphasised CMAL’s unhappiness ‘in respect of the position this would leave the company if the ship failed to perform or the shipyard went into liquidation’. Mackay’s attention was drawn to the draft letter. With that exchange, a large proportion of the financial risk on the ferry contract entered public hands. If the worst happened, CMAL would be ‘looked after’ at public expense.

These manoeuvrings remained hidden until this spring. When journalistic interest and public disquiet over what was now known as the ‘ferries fiasco’ at last made them public, they were too complicated to be quickly understood. The appetite instead was to name guilty men. Who had given the go-ahead for these vessels? Nobody would own up to the decision and no written evidence could be found. Then, on 11 May, the current SNP transport minister, Jenny Gilruth, told the Holyrood parliament that ‘I have some good news to share … The missing document has been found!’ She went on to say that

the document is an email that makes clear who approved the decision to award the contract to build vessels 801 and 802 to Ferguson’s shipyard. Sent in response to the key submission on 8 October 2015 [the email sent by the official at Transport Scotland to the minister] it is dated 9 October at 14.32 and it reads: ‘The minister is content with the proposals and would like [them] to be moved on as quickly as possible please.’ Presiding Officer, the email was sent by the office of the minister for transport and islands. Presiding Officer, I hold in my hand the irrefutable documentary evidence that this decision was made rightly and properly by the then transport minister, Derek Mackay.

She claimed that the email ‘destroys the opposition’s ridiculous conspiracy theories that another minister made this decision. It destroys their unfounded speculation that there was a ministerial direction given.’ Did it? A few months after sending that email, Mackay succeeded Swinney as finance secretary. He was young, just under forty, and seemed to be a growing force inside the party and the government. Then in February 2020 the Scottish edition of the Sun carried transcripts of dozens of social media messages he had sent a 16-year-old boy. No law had been broken, but Mackay resigned as a minister and stood down as an MSP in last year’s Holyrood elections. A government in need of a scapegoat couldn’t have found a more obvious one, but if that was his role, his written evidence to the committee bore no trace of hurt or resentment. It was a model of pious opacity. Asked whether he’d told FMEL that a BRG was not required, he replied: ‘This would be a matter for CMAL. However, I note the interpretation of FMEL of the written ministerial response [his own] to Stuart McMillan MSP dated 2 February 2015 as detailed at evidence to your committee. This letter was a factual response to an MSP inquiry at the time.’ He hadn’t assessed the risks for himself: ‘The recommendation in the submission was “to proceed to contract award”. The submission had followed the necessary process, procurement assessment and milestone stages, therefore I had confidence in the recommendation, but appreciated that risks had been identified and understood to be resolved.’ Mackay appeared in front of the committee on 8 September and stuck to the same line. ‘I don’t think there was a political agenda and I don’t think it was rushed at all,’ he said.

Who had made the recommendation that the contract should be awarded? Had there been a recommendation at all? The email from Transport Scotland to Mackay on 8 October simply sought his agreement ‘to proceed to contract award’. That might have implied recommendation, but the body which in normal circumstances would have made that recommendation had deliberately withheld it. In earlier evidence to the audit committee, another Transport Scotland official said that CMAL ‘was content to award the contract and was seeking approval from the minister to do so’, but the CMAL witnesses adamantly denied this. The official ‘said that the board was content with the contract, and we were not,’ Østergaard said. ‘If we had not been given the undertakings from the Scottish government, we would not have placed that order.’ ‘There is no recommendation to award the contract,’ McNeill said. In his September evidence Mackay claimed that CMAL officials would have signed off the contract. Ministers ‘don’t ordinarily sign contracts’, he said.

So CMAL had signed off the contract without recommending it. How had this happened? Transport Scotland knew what ministers wanted; ministers knew they needed Transport Scotland’s approval; CMAL’s objections had been quietened by the letter of comfort. There was something almost Johnsonian about it – Let’s Get Ferries Done!

If all had gone well with the building of the ships, none of this would have mattered much. But almost from the start, construction went badly. CMAL first reported problems to Transport Scotland’s steering group in December 2015. A year later, fourteen months into the contract, the government knew there was a risk of late delivery, a possibility that early in 2017 became ‘highly probable’.

To the outsider, shipbuilding seems relatively straightforward: the buyer tells the builder what they want, and leaves the builder to get on with it. According to the BIMCO contract, the builder carries the full responsibility for the ship’s design and construction, and the buyer has no right to intervene. There is intervention, nonetheless. A ‘classification society’ (usually Lloyd’s Register) is contracted by the shipbuilder to ensure the vessel complies with its rules and regulations; it approves the plans for the vessel and regularly examines it during construction. Later, a ‘flag authority’ (in the UK, the Maritime and Coastguard Agency) inspects the vessel and certificates it for issues such as passenger safety and sets the geographical limits of its operation. These people come and go; a more constant onsite presence is the team from the buyer, in this case between three and six CMAL staff who turned up at the shipyard twelve hours a day, seven days a week. They were there to monitor progress, to inspect and to advise. Any concerns or recommendations – a badly fitting part, unsatisfactory workmanship – would be passed to FMEL through what are known as owner observation reports (OORs). Between the start of construction and August 2019, when FMEL entered administration, CMAL had issued 346 OORs, roughly half of which had been resolved, with the remainder waiting their turn or resisted because FMEL thought they were unnecessary. (The contract said FMEL had to comply with CMAL’s ‘reasonable demands’ but didn’t define what these were – one of several fuzzy contractual clauses criticised in the Audit Scotland report.)

The biggest area of contention, however, lay closer to the start of the shipbuilding process, with the conversion of the buyer’s specifications into a ‘conceptual’ design, attached when the job goes out to tender, and later developed by the successful bidder into the far more detailed plan the builders will work from. McColl’s argument is that the problems stemmed mainly from CMAL’s failure at this stage: ‘It became evident as we got into this contract that they hadn’t fully developed their ideas of what they wanted … so they came in finalising their ideas as we were building it,’ he said during our conversation in May. He’d commissioned a report from an independent group of naval architects and marine engineers, which endorsed his view. ‘It said that CMAL had hurried the development of the spec and had not spent enough time flushing out what they wanted, or been clear about what they wanted or the consequences of what they wanted.’ He added, ‘again with hindsight’, that this might have been connected with the Scottish government’s rush to make an announcement ‘for PR reasons’.

In McColl’s version of events, the most spectacular consequence of CMAL’s hurry was the premature launch of hull 801. The plan had been to build the two sister ships – identical twins, as he understood it – simultaneously, side by side on the slipways. Since the working space around the slipways was cramped, partly thanks to FMEL’s new offices and fabrication shed, the yard planned to start building the ships from the stern, the end nearest the water, rather than from midships, which is more usual. This would enable materials to be supplied from the bow end rather than the narrow space at the sides.

But then, again according to McColl, CMAL discovered that the vessels could not be identical. Hull 802, destined to cross the Minch from Skye to Harris and North Uist, needed to sail at an ‘optimised’ speed of sixteen and a half knots rather than the ‘optimised’ speed of fourteen and a half knots planned for both ships. Engines and propellers had already been ordered from Wärtsilä in Finland and couldn’t be adjusted to the new speed. The solution (to change the flow lines around hull 802’s stern) meant the stern had to be redesigned. That would take time, and building both ships from the stern needed synchronicity. Meanwhile, as McColl said, ‘we had to build something’ to keep the project moving forward and workers employed. So the yard began fabricating the midships, the box-like centre sections. McColl said Lloyd’s had signed off on the drawings but CMAL refused to. ‘They had no right to interfere but they did interfere,’ he said. ‘We had the people in the yard, we had the steel, it was all sitting there … so yes, we did start fabrication before CMAL had signed off on the final design, because if we’d waited for the signing off of the final design there would not be a plate cut yet.’

FMEL had the right to choose any building sequence it wanted to, and what it eventually chose was largely dictated by Lloyd’s approval of the more straightforward midships sections. Money also played a role. Shipbuilding contracts typically pay the builder in five equal parts, but to help its cashflow, FMEL had asked for a payment schedule divided into fifteen parts, each of them triggered by a ‘milestone’: 2.9 per cent when the first steel was cut, 7.5 per cent when a quarter of the fabrication was completed and so on. In its evidence to the audit committee, CMAL said that the shipyard had often begun fabrication and construction without its approval, or that of Lloyd’s or the Maritime and Coastguard Agency. This strategy, intended to maximise income by reaching ‘milestones’ more quickly, is known as ‘fabricating at risk’ or ‘chasing steel’, and in Port Glasgow often led to expensive reworkings, which added to the shipyard’s bill. In mitigation, Audit Scotland’s report complained that many of the milestones were poorly defined and ‘had no link to quality standards’. In fabrication, for instance, were they to be triggered when a part was finished or when it was fitted to the ship?