Machu Picchu is not very old. Despite giving the impression of great and mysterious antiquity, the construction of the site was roughly contemporary with Brunelleschi’s completion of the duomo in Florence. Built as a royal estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti, the citadel was occupied only for a century or so before being abandoned during the Spanish Conquest; it was dissolving into the cloud forest at more or less the same time that the much older Tintern Abbey was also left to ruin, after Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

Orthodox European history works on a unidirectional timeline: in spatiotemporal terms, Machu Picchu, Tintern and Florence are distantly located beads on a universal string, existing in parallel, always staying the same distance from one another in both three and four dimensions. Museums are usually organised along these lines, too: every artefact has an origin and a date, fixed as accurately as possible in a past that has definitely finished. The mummies in the British Museum are no longer alive, the wars and the punitive expeditions are long concluded, the regrettable dealings are water under the bridge. Nothing that has already happened can be changed, and the events of tomorrow are yet to occur.

But in the Andes, time is experienced in a different way, and the people who made the objects that populate Peru: A Journey in Time at the British Museum (until 20 February) would have had a quite different conception. Andean time is not a single irreversible flow: the future, the past and the present are imagined as three strands, taking place in simultaneous realities, and arranged as a triple spiral. If these temporal arms are somewhat out of sync, it’s the future that is behind, since it’s invisible. The past is in front of you: what happened there, or some of it, can be seen. Events on one strand may affect the others, and not in a linear way but in a direct one. Future and past generations are fully alive in Andean time, living on in their times as equally and immediately as you do in yours. Things and places can move between streams, or can be present in more than one; the Andean landscape is alive with concurrent past and future realities, and objects can forge connections between them.

The ways in which Andean plural time might play into debates about the return of contested museum objects has not been lost on the organisers of the show. Because cause and effect are not in a fixed order, things that have already occurred can still be transformed or reversed. The cause of an event might not have fully happened yet – the future or present can stretch across and change or undo it. What would the debate over the Benin Bronzes or the Elgin Marbles look like if the past were conceived in this manner, rather than being looked at through the flattening lens of what the catalogue calls ‘museum time’? People in the Andean past still have ‘rights and relevance’, because they are still alive: the living dead might be ‘not too happy’ about the way their lives are presented in a museum, and this should be taken into account. (Presumably, some of the dead people represented by the countless sets of human remains in the British Museum might be less than pleased with their post-mortem treatment: museums are one of the few places where the widespread taboo on gawking at human corpses, as well as the cultural and legal interdictions on leaving them unburied, are suspended.)

The curators have tried to square this circle in part by including some short and fascinating films of contemporary Peruvians who still practise pre-Columbian arts. Manuel Choqque, whose community has taken up farming techniques that were developed in the Inca period agricultural research village of Moray, grows crops including potatoes and maize in the traditional manner. Potatoes are one of indigenous Peru’s great gifts to the world: first cultivated in the foothills of the Andes around ten thousand years ago, there are more than four thousand different varieties in Peru today, and the pictures of Choqque’s knobbly, multi-coloured spuds are as much an aesthetic marvel as anything else on display. Elsewhere, a doughty fisherman called Victor Huamanchumo is shown building a precarious-looking reed boat, of the kind that can be seen in Moche ceramic figures from the first millennium ce. ‘These ways of … using knowledge passed down through generations are important to hold on to.’

But the films can’t do justice to the temporal conundrums of Andean philosophy and the explanations of what this kind of time means in practice seem a bit limited. The catalogue essay on the subject bashes away unimaginatively at Western cultural chauvinism and predictably sticks it to the boringly chronological timelords of the museum itself, but I couldn’t help thinking that the conquistadores who ruptured millennia of Andean history arrived in the Americas with a vision of time flexible enough to allow that Jesus died once 1500 years ago, dies again once every year at Easter, and is also dying on the cross for all eternity. Renaissance paintings of the infant Christ often show him holding a goldfinch, its crimson face already stained with blood from the crown of thorns. Pizarro and his men would have believed that Jesus was in some sense permanently alive, and able to intercede in current events – a state of affairs hardly less temporally tangled than the Andean conception.

European sacred and folk thought has always been a lot weirder than ‘museum time’. But museum time is still powerful, and at the BM it seems to have gained the upper hand over Andean plurality. The exhibition is a straightforward oldest-to-newest array, and the overlapping civilisations and empires of the Peruvian past are laid out on a conventional timeline, with the Chavin and Cupisnique cultures beginning the story three thousand years ago, and the Incas ushering the visitor out into the ongoing post-conquest present.

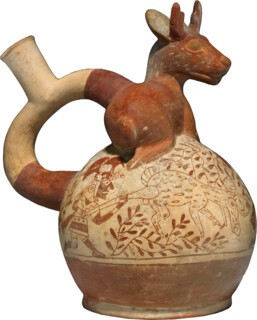

The earlier material is spectacularly confident. The civilisations of the Andes were master potters, and earthenware was the artform of choice for millennia. The most typical is the ‘stirrup vessel’: a sort of moulded jug with a stirrup-shaped handle, topped with a tubular spout. Why this should have been the object through which depictions of animals, people, deities and abstract forms were expressed goes undiscussed but, whatever the reason, nearly everything is a jug of some kind, and the level of technical and aesthetic sophistication is sometimes breathtaking. The Moche works, dating from between 100 ce and 800 ce, are especially stunning. There is a set of portrait vessels as minutely realist as the finest Old World portraiture of the same or any other period (like a set of Toby jugs made by Donatello); a stylised deer is sculpted in soft animal geometries, with ultra-modern looking kawaii eyes and ears; a gorgeous abstract vessel takes the form of a stepped volute – it may be a representation of the culture-defining natural forces of wave and mountain, but could just as easily have materialised out of a late Kandinsky.

The Inca material seems enervated by comparison, and the colonial era objects bear traces of the catastrophe that had overcome their makers in the form of representations of Spaniards and people in European dress. A set of silver fastening pins called tupu have lost their historical form in favour of etiolated designs seemingly drawn from European dessert spoons. The indigenous objects are interwoven with contemporary Spanish texts and images, giving them the melancholy look of material from the end of time. As well as having plural timelines, Andean societies thought that the whole world was periodically ended and renewed in cyclical universal cataclysms; Pizarro’s capture and murder of Atawallpa, the rout of thousands of elite troops by a few dozen grizzled Spanish horsemen and the stripping of gilded Cusco must have seemed to prove them right. Given that modern history has turned on the discovery of the Americas, who is to say they weren’t?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.