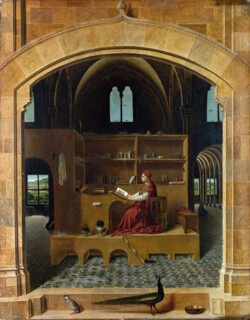

Last March , in response to the pandemic and the confinement of daily life to the walls of my home, one of the pictures in my care as a curator at the National Gallery assumed a new significance: Antonello da Messina’s St Jerome in His Study. Here, a Sicilian artist working in Venice in the mid-1470s represents the early Christian saint in the nonpareil of home offices. St Jerome sits reading at his desk on an elevated podium; other books and artefacts line the shelves around him. The architecture is lofty, gothic and fantastical. Framing the scene is a stone archway with a peacock, a partridge and a metal bowl on the threshold. In the seclusion of prayer and study, the painting suggests, the world reveals all its riches. I felt rather jealous.

Little is known about the artist who painted this image. Antonello was born in the harbour city of Messina in Sicily around 1430 and died in 1479. No more than forty of his paintings survive and they are widely dispersed. Relatively few institutions are willing to lend their Antonellos, partly because of their scarcity and partly because most of the works are painted on wood, so that moving them is especially fraught. Nonetheless there have been four exhibitions outside Sicily in the last fifteen years – in New York (2005), Rome (2006), Rovereto (2013) and Milan (2019). These shows, and the books that accompanied them, have been an important means of consolidating our knowledge of Antonello and appreciating the quality of his work. Only two of the books – from the Met show in New York and the more recent Palazzo Reale exhibition in Milan – are currently available in English. (It is a particular shame that Mauro Lucco’s catalogue of the Rome exhibition – the model for the Milan catalogue – and his catalogue raisonné of 2011 are no longer in print.)

These exhibitions indicate Antonello’s enduring popularity in Italy. Like Vermeer, he has always inspired praise from novelists and poets as well as art historians and collectors. His portraits invite comparison with Leonardo; his religious images are as moving – in different ways – as Raphael’s; his landscapes are as mesmerising as anything by Giovanni Bellini. The reason he hasn’t enjoyed the same fame as these artists is partly the result of longstanding confusion as to who he was and what he created, and also the geographical biases of later periods. Take St Jerome in His Study. The earliest description of the painting (an important loan for the Milan show, as it was in Rome thirteen years earlier) comes from an account of 1529 by the Venetian nobleman Marcantonio Michiel. He was describing the collection of Antonio Pasqualini, a silk merchant, and already – only fifty years after it was painted – the question of St Jerome’s authorship troubled Michiel. Could it really be, as some people claimed, ‘by the hand of Antonello da Messina’? Or had the figure of St Jerome been reworked by that obscure yet talented Venetian artist, Jacometto Veneziano? Others – Michiel implicitly includes himself – ‘attribute it to Gianes [Jan Van Eyck] or Memelin [Hans Memling]’. Several years later, in January 1533, he returned to take further notes on the painting. He praised the ‘buildings in the Flemish style’, the ‘natural, minute and finished’ landscape, and the study itself with its ‘portraits’ (ritratti) of a peacock, a partridge and a barber’s basin. Finally, he was tantalised by the little piece of paper (litterina) attached to the desk. As Michiel points out, it appears to bear the name of the artist but, on closer inspection, reveals not a single discernible letter.

It’s hard not to share Michiel’s frustration. Antonello’s facility with different styles of painting – Northern European, Provençal, Venetian – has meant his works have often been attributed to others. In the 18th century, St Jerome was thought to have been painted by Dürer; in 1854, when the picture was sold at Christie’s to the banker Thomas Baring, it was once again under the name of Van Eyck. At this point, another scholar examined the vexed question of authorship. Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle (1819-97), an Italian nationalist and art historian of modest means, visited Baring’s London house three times in a month to study and to draw St Jerome. His notes – like those of Michiel – are deposited at the Marciana Library in Venice (and are the subject of an excellent essay by Giovanni Villa in the Milan catalogue).

Cavalcaselle’s connoisseurial methods were meticulous. First, he diligently copied the painting. On his second visit, he analysed closely the view from the window and certain details: the ceramics beside the cat, which looked to him Venetian, and the partridge, ‘popular in the Veneto school’. A week later, he made a detailed drawing of St Jerome himself, commenting on the way the hood and cap recalled Bellini, while the folds of drapery were characteristic of Antonello. By the end of September he was certain and St Jerome featured among Cavalcaselle’s manuscript catalogue of Antonello’s autograph works. Several decades later, in 1894, the painting entered the National Gallery’s collection. Its attribution to Antonello has never been in doubt since.

Working out what Antonello di Giovanni d’Antonio (as his contemporaries knew him) painted is complicated by the fact that the documentary record relating to his life and work is so sparse. This is not unusual of Quattrocento painters, even those whose reputations have remained high. There are only 44 surviving documents that mention Antonello’s name, and around half of them were discovered in 1902 by two historians, Gioacchino Di Marzo, prefect of the Palatine Library in Palermo, and Gaetano La Corte Cailler. The destruction of Messina’s city archive in an earthquake six years later ended any hopes of finding anything more than footnotes.

Most of the surviving documents concern the prosaic life of small-town Italy five centuries ago: trade consignments, marriage negotiations, sale agreements and contracts. From these we learn that Antonello was the son of Giovanni, a stone or marble cutter, and his wife, Margherita. His paternal grandfather owned a ship that traded between Messina and Reggio Calabria on the Italian mainland. His name is first recorded in a document of March 1457 concerning a banner that was being made for a confraternity in Reggio. We know that Antonello founded a workshop there, but by 1460 he seems to have returned to Messina: there is a record of the arrival of his household in a brigantine crewed by six men, hired by his father. By this time he was married and had children, servants and household furnishings that needed transporting. Five years later, he bought a house in his home city. These documents show that Antonello was extremely busy in Southern Italy and Sicily, but all the artworks they mention are now lost.

We know nothing more of Antonello’s life until October 1471, when he signed an agreement to make a painting for the confraternity of Santo Spirito in the hill town of Noto, where his sister lived. In 1473 he married his daughter, Caterinella, to Bernardo Casalayna, a goldsmith, and in the same year delivered his only public commission for Messina, a polyptych or many-panelled altarpiece for the church of San Gregorio, the central panel of which is the first of his works to be legibly signed and dated. It seems certain he had travelled to Venice before 1475. Later that year, the duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, requested his ambassador in Venice to seek out this ‘ceciliano’ and lure him to Milan to replace the court portraitist, who had recently died. At this time Antonello was working on an altarpiece for the Venetian church of San Cassiano (fragments remain in the Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna). It was still incomplete in March 1476 when Pietro Bon, who commissioned the altarpiece, estimated that ‘maistro Antonelo’ would need at least twenty days to bring to fruition ‘what will be among the most excellent works of the brush, within and beyond Italy’. By September Antonello had returned to Messina to pay the last instalment of Caterinella’s dowry. He died there sometime after 14 February 1479, when he dictated his will ‘lying ill in bed’, and before 11 May, when the will was opened and read. He would have been about fifty. In November that year, his widow, Giovanna Cuminella, married a Messinese notary.

The Venetian evidence apart, these fragments give little insight into Antonello’s career and personality or what contemporaries thought about him. We don’t know where and with whom he trained, or any details of his early career in Sicily and Southern Italy, or why so much of his surviving oeuvre comes from a handful of years at the end of his career. The absence of any documentation between 1465 and 1471 has allowed art historians to impose their own ideas. Like Piero della Francesca, the other exceptional Italian painter of this period to work largely outside Florence or Venice, Antonello has become a means of justifying and explaining a range of ideas and practices.

This process began in the decades after his death. Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) was the first to suggest that Antonello went to the Low Countries. According to his narrative, Johannes of Bruges (Jan Van Eyck) was charmed by Antonello and taught him all his secrets. This was a clever way of explaining Antonello’s exposure to Northern Renaissance painting, and of accounting for the arrival of oil painting in the Mediterranean basin, but there is no evidence for it whatsoever. Antonello could have seen Northern European painting, or derivatives of it, without travelling there, and if he went anywhere outside Italy, it is more likely to have been Southern France. Furthermore, Antonello used oil paint in a way that would have horrified Van Eyck. If you scrutinise a painting by Antonello under the microscope, it begins to dissolve before your eyes. Although he appears to have painted every detail, in fact his technique is often loose and, as Gianluca Poldi describes in the Milan catalogue, the impression of dazzling precision is actually the result of countless rapid strokes.

Vasari’s account was followed in 1648 by that of the Venetian art historian Carlo Ridolfi (1594-1658), who claimed that Bellini had visited Antonello’s studio in disguise to learn how to paint in oils. This was believed well into the 19th century and the scene was even made into a painting by Roberto Venturi as late as 1870. But it’s clear that Bellini (and others) were adept at oil painting long before Antonello visited Venice. More recently, the art historian Roberto Longhi (1890-1970) viewed Antonello as the link between the Flemish and Venetian traditions, and argued – in the absence of any documentary evidence – that Antonello must have spent time in Central Italy and been exposed to the work of Piero della Francesca. During this interlude, he argued, Antonello travelled to Venice, where his knowledge of perspective and his method of painting light inspired the experimentation for which Bellini and his many followers became so famous. Despite Longhi’s eloquence, and the passion of many of his intellectual followers, including Ferdinando Bologna (co-curator of the Rovereto exhibition in 2013), there is no need to accept this assessment of Antonello as a frustrated genius who needed the example of Piero to break free. This has more to do with later constructions of centre and periphery, and the continuing bias against Southern Italy in historical narratives, than with a measured assessment of the evidence.

Antonello’s significance as an artist can’t simply be attached to his years in Venice. He is better understood, as Gioacchino Barbera argues in the Metropolitan Museum catalogue of 2005, as a Southern Italian, and a Sicilian.* Recent work, especially that of Mauro Lucco, has made it possible to ask why there has been so much resistance to the idea that one of the greatest artists of the early Renaissance worked in Calabria and Sicily rather than Florence and Venice, and what we can reasonably infer about Antonello’s formation and artistic career from the evidence available.

Antonello seems to have been destined for an artistic career. He and his younger brother, Giordano (their father’s favourite), were initially placed with a local draughtsman. Drawing was the basis for working as a mason, a painter or a sculptor, so the training might have taken the brothers in any direction. Messina, a city of about twenty thousand inhabitants, was ruled for most of Antonello’s adult life by King Alfonso of Aragon and his illegitimate son, Ferrante. As a consequence there were strong links with other territories connected to the Aragonese dynasty, including Catalonia and the Balearic Islands. Messina was also an important stop-off for three Venetian convoy routes, connecting the Low Countries, Provence and the Western Mediterranean.

It’s very likely that Antonello first saw copies of Northern European and Provençal painting in Sicily. As well as having their own distinct synthesis of classical Greek, Italo-Byzantine and Islamic traditions, Sicilian painters were receptive to ideas from further afield. We know that by late in Antonello’s career paintings by Petrus Christus, Jan Van Eyck’s successor in Bruges, were in Sicily. Antonello would also have seen avant-garde Flemish and Southern French painting in Naples, where he appears to have studied with Niccolò Antonio Colantonio, the city’s leading painter, sometime after 1445.

Colantonio is known as a copyist of Van Eyck, so Antonello’s first encounter was probably one of these works. Other works by or derived from Van Eyck could also be seen in Naples, most important of which was the (now lost) Lomellini triptych owned by Alfonso of Aragon, though it is debatable whether it would have been accessible to the young Antonello. Even if he didn’t see it first-hand, he may nevertheless have responded to the panel showing St Jerome in his study: a St Jerome by Colantonio, painted in the mid-1440s, is almost a mirror image of Van Eyck’s surviving example of the subject, now in Detroit. In 2001, another St Jerome by Antonello was displayed beside Colantonio’s painting in a special exhibition in Naples. The juxtaposition usefully illustrated the way Antonello worked through and adapted the Eyckian model. Van Eyck and Colantonio both painted the saint’s study as a closed, coffered, even claustrophobic room. In Antonello’s version, the room – although crowded with books and shelves – is open to the world and, by implication, to ideas.

In Naples, Antonello would have been exposed to other artists from north of the Alps. The angular, almost abstract quality of some of his early works – including the Virgin and Child with a Franciscan Donor, the Virgin Reading (a work not accepted as autograph by all scholars) and the Portrait of a Man, now in Pavia – has most in common with Provençal painters such as Enguerrand Quarton, who was probably in Naples between 1438 and 1442 in the entourage of René d’Anjou (the duke controlled Naples for four brief years before being expelled by Alfonso).

Some have suggested that Antonello did travel north, but to Provence rather than Flanders, before his next documented presence in Southern Italy in 1457. We are unlikely to know for sure. What’s important is not where he was exposed to these traditions but that he was. In a small painting of the Crucifixion now in Sibiu, generally agreed to be an early work, the mourners are striking for their stylised, simplified faces and expressive hands. The foreground landscape and the figure of St John recall the work of artists at the Burgundian court, as well as the Bruges painter Petrus Christus (some scholars have pointed, less convincingly, to connections with Fra Angelico and Domenico Veneziano, who were active in Florence).

The landscape of the Sibiu Crucifixion is clearly based on the town of Messina and the nearby straits. Several identifiable monuments can be discerned, including the Basilian monastery of San Salvatore and the harbour. The galleys coming and going speak to the centrality of trade and transportation to the Messinese economy. Another early painting, the tiny double-sided Ecce Homo/St Jerome, similarly connects Antonello’s ‘real world’ with the continuing reality of Christ’s suffering – a leitmotif of the devotio moderna, the main theological trend of Antonello’s time. As Federico Zeri has suggested, the considerable damage to St Jerome’s body may have been caused by the owner’s having carried the painting in his pocket.

The outstanding work of this period is a small portrait of an unknown man, now at the Museo Mandralisca in Cefalù, which was included in both the Milan and New York exhibitions. The man appears to be smiling, but there is something ironic, even mocking, in his expression. The scratch across the mouth and eyes may be the result of deliberate vandalism – a response to a painting that on close inspection proved too provoking. The Sicilian writer Vincenzo Consolo drew on the theory that the man was a sailor for his novel The Smile of the Unknown Mariner (1976), about the historical figure Baron Mandralisca, who acquired the painting on the island of Lipari, where the local apothecary was using it as a cupboard door. (In fact we know now that the painting is of a nobleman.) Consolo characterised the smile as belonging to ‘someone who has seen much and knows much’; his friend and contemporary Leonardo Sciascia (best known outside Italy for The Day of the Owl) commented on the ‘Sicilian’ nature of Antonello’s portrait. ‘In Sicily, the game of resemblances is … delicate, sensitive … Who does the unknown man of the Museo Mandralisca resemble? … He just resembles. That’s all I can say.’

Antonello’s ability, in the Cefalù man and other portraits, to create distinctive and beguiling characters, is matched in achievement by his interpretation of the Annunciation. Most 14th and 15th-century depictions of the subject are similar in their iconography: Mary is shown within some man-made structure – whether a porch, as Fra Angelico conceived it, or a private room, as Carlo Crivelli did – to underline her virginity and her separation from the world. Antonello’s Virgin Annunciate, presumably made for private devotion, although we don’t know for whom, is quite different.

Taking the approach he had developed in his portraits, Antonello invites us to witness a supremely private moment. Here is a young girl, her head covered in a heavy cloth of apparent simplicity, although its bright ultramarine indicates that this is no ordinary teenager. The image is pared down to its bare essentials: the girl, her book and her inscrutable face. We aren’t participants in this action – as Luke Syson has pointed out, this would have been too much for even the most ardent exponents of the devotio moderna – but privileged observers. Mary’s measured self-possession is astonishing. She raises her right hand, to silence the archangel (and us), and prepares to turn back to her book. There is nothing quite like it in Renaissance Italian art.

Because of the gaps in the documentation, art historians have tended to assume that Antonello was a slow developer, goaded into action and innovation by his visit to Venice and by what he might have seen – in Urbino, Rimini, Pesaro, Ferrara and Padua – on his hypothetical route to the Republic of St Mark. These are unknowables, but works like the Annunciation and the Portrait of a Smiling Man demonstrate the exceptional ambition, novelty and achievement of his work before Venice. It is likely that some of this, at least, was known to his Venetian patrons: it’s hard to imagine an experienced Venetian statesman like Pietro Bon taking a chance on an unknown artist.

For all this, the quantity, and quality, of the paintings made as a result of Antonello’s stay in Venice is remarkable in an artist with so few surviving works. Writing from the city in 1475, Matteo Colacio, a Sicilian living in Venice, commended Antonello as one of the very few contemporary artists whose work was comparable to the masters of antiquity. From the little more than a year of Antonello’s visit we have portraits such as the Louvre Condottiere, whose slightly pursed lips and defiant expression explain why he has been identified as a military man, and the National Gallery Portrait of a Man, a sitter of more modest status, in a red hat and dark doublet, who disarms us with the frankness of his gaze. We have private devotional works, such as the St Jerome, and the Antwerp Crucifixion, particularly striking for the contrast between the contortion of the thieves’ bodies and the quiet beauty of the landscape (a more idealised view of the Straits of Messina than that of the Sibiu painting). The Annunciation, now in Palermo, may have been painted in Venice. And perhaps most significant of all – certainly in a Venetian context – are the San Cassiano altarpiece and the St Sebastian executed after Antonello had left the city.

We find praise of the San Cassiano altarpiece shortly after it was installed – by Matteo Colacio; the Venetian diarist Marin Sanudo; the Florentine Giovanni Ridolfi; Raphael’s father, the painter and writer Giovanni Santi; the Venetian humanist scholar Marcantonio Sabellico; and later by Marcantonio Michiel. At some point before the late 1630s it was damaged and cut down, and is now known through copies by David Teniers the Younger, but in its time it was an important step towards the most significant development of Venetian public art, the sacra conversazione, where divine, sainted and human figures participate, as apparent equals, in a single narrative in a single space.

Antonello’s St Sebastian makes one wonder what he might have achieved had he lived longer. Painted for the altar of St Roch in the Venetian church of San Giuliano, it must have been commissioned as an ex-voto offering during an outbreak of plague. St Sebastian is tied to a tree in the middle of the image; the arrows shot at him have pierced his flesh, but haven’t yet killed him. In the background, the men and women of a lagoon city, presumably Venice, go about their business. Soldiers loaf and chat, unaware that the martyred saint is still alive; one of them snores (his open mouth demonstrates Antonello’s command of foreshortening); a woman holds her sleeping child close to her chest while she walks; others idly observe the scene from a balcony. Many of the later achievements of Venetian narrative painting – from Bellini’s St Mark Preaching in Alexandria to Carpaccio’s Ursula series – were influenced by this altarpiece, made not in Venice but in Messina. Given the history of Sicily, and in particular of Messina, ravaged by a succession of earthquakes and other natural disasters, we are lucky that so many of Antonello’s paintings have survived, even in compromised form. This itself contributes to the power of the remaining works.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.