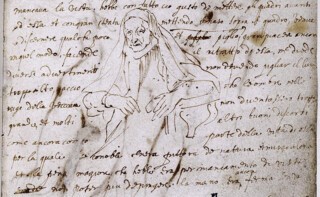

In July 1624, two artists met in Palermo during an outbreak of plague which killed thousands of people, including the city’s ruler. The younger artist, Anthony Van Dyck, made a quick pen and ink drawing and wrote down his impressions of Sofonisba Anguissola, then apparently 96 years old and almost blind. He was struck by her intellectual curiosity, her politeness and good manners, and her continuing passion for paintings:

Although she was lacking in good eyesight because of her old age, she nevertheless found pleasure in placing the paintings in front of her and, with great effort, pressing her nose up close to the picture, was able to make out a little of it … In making her portrait, she gave me several pieces of advice: not to raise the light too high, so that the shadows would not accentuate the wrinkles of old age, and many other good suggestions, and moreover she recounted the part of her life in which she was recognised as a miraculous painter from life, and the great torment she had known in not being able to paint anymore, because of her failing eyesight, though her hand was still steady, without any trembling.

It was far from usual for young men like Van Dyck to express admiration for blind, elderly women. Yet the meeting made a deep impression on him. Not only is this the longest description of a person or a painting to be found in the sketchbook he kept during his Italian years, it is also the only one that is dated. Later in life, he still remembered Sofonisba, claiming he had learned more from their conversation than from the works of far more famous painters. A small portrait he made of her survives at Knole in Kent. It is ignored by most visitors to the house because, while Van Dyck remains one of the most influential artists in the Western canon, the painting is a modest work and Sofonisba isn’t yet a name to conjure with, unlike her younger contemporary, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1654). Things are, however, beginning to change. Sofonisba and her legacy are addressed by two recent books: the catalogue of an exhibition held at the Prado, curated by Leticia Ruiz Gómez, and a monograph by the American art historian Michael Cole.

Around 1535, a girl was born in the city of Cremona, fifty miles south-east of Milan, to Amilcare Anguissola and his second wife, Bianca Ponzone. Amilcare was a member of the minor nobility and Bianca the daughter of a local count. The Anguissola family claimed descent from the Carthaginians and the couple named their daughter after a celebrated Carthaginian noblewoman, renowned for her beauty and her devotion. It’s not surprising that we don’t know exactly when Sofonisba Anguissola was born. In early modern Europe, the arrival of a girl was rarely a moment for rejoicing. The most that could be hoped was that she would marry respectably, incur no unnecessary expense and pass from the world leaving no trace, except, of course, her legitimate, and preferably male, offspring. As a result, it can be hard to piece together even the lives of those women, such as Sofonisba, whose experience stood outside the norm. And what we know of her rarely comes in her own words: it is principally hearsay, reported by others or recorded in legal documents.

The Anguissolas were status-rich but cash-poor and lack of money must have been a salient feature of Sofonisba’s childhood. Her father’s commercial ventures – including a stationery business, a cheese shop and a pharmacy – all failed to flourish. Nor were her mother’s more prosperous relations prepared to offer much tangible help. The situation became increasingly precarious with the regular arrival of more mouths to feed. By 1546, Amilcare and Bianca had three, perhaps four, daughters, all under the age of 11. (The only son among their seven children, Asdrubale, was born in 1551.) At this point, Amilcare took an extremely unusual decision. He sent the two eldest girls, Sofonisba and Elena, to live in the household of the Cremonese painter Bernardino Campi (1522-91). They had already received the sort of humanistic education recommended for noblewomen by Baldassare Castiglione: ‘knowledge of letters, music, painting … how to dance and make merry’. Now they would have the further gilding of a professional training from Campi and another important local artist, Bernardino Gatti (c.1495-1576).

Amilcare’s decision exposed his daughters to great risk – as a young woman, Artemisia Gentileschi was raped by her perspective tutor Agostino Tassi – but it appears that the Anguissola girls were well looked after. Elena entered a convent, perhaps with her artistic skills as her dowry, and Sofonisba became, as the art historian Rosanna Sacchi puts it, her father’s only successful business enterprise. Amilcare made use of his aristocratic and humanist connections to promote her achievements to the most influential people of the day, sending examples of her work to Michelangelo, the duke of Ferrara and the pope. By 1550, when she was aged about 15, it didn’t seem ridiculous for the local bishop and scholar, Marco Girolamo Vida, to claim that Sofonisba was ‘among the most worthy painters of our day’. The family home in Cremona became a showcase for her talents. Vasari, who proudly attested to owning one of her drawings, visited her there and recorded seeing her masterpiece, The Chess Game, as well as a group portrait of Amilcare, Asdrubale and Minerva Anguissola. The Anguissola house, he wrote, was the ‘home of painting, as well as all the virtues’. The miniaturist Giulio Clovio and other visitors to Cremona had their portraits painted by Sofonisba, and numerous correspondents, among them Michelangelo and his friend Tomasso Cavalieri, communicated with her through her father.

Amilcare, meanwhile, was working towards a far greater prize. In 1558, he wrote to Michelangelo of his hope that Sofonisba would receive a ‘means of living’ from Philip II of Spain, at that time the most powerful man in Europe and ruler of nearby Milan. The following summer, Philip wrote to formally request that Sofonisba travel to Spain to serve his new wife, Isabel de Valois. She arrived in time to attend the wedding at Guadalajara in January 1560. The next 13 years of her life were spent at the Spanish court, first as lady-in-waiting to the queen; then, after her death in 1568, in the households of her young daughters, the infantas Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela, and of the new queen, Anna of Austria. But exactly what Sofonisba did in Spain remains a matter of some conjecture. It’s evident that she was a much loved courtier, valued by Isabel and Philip as much as for her grace, humour and skill in dancing as for her artistic prowess. Although she continued to paint, only five of the 34 paintings that most experts accept as her work date to her Spanish period. Technical studies undertaken in preparation for the Prado exhibition show that she adapted her style to the conventions of the Spanish court. She worked closely with Alonso Sánchez Coello, the court painter, even using canvases that had been prepared in his workshop. From what we can tell, her role seems to have been more that of teacher than practitioner, making painting a legitimate accomplishment for aristocratic women.

In 1573, Sofonisba was married by proxy to Fabrizio de Moncada, a Sicilian nobleman of Spanish descent. She brought with her a dowry, provided by the queen, and a further thousand ducats from the customs houses of Palermo and Messina. By October, she was in Palermo. Painting continued, but only as a pastime, as befitted a wealthy noblewoman. Her most important work of this period is an altarpiece, the Madonna dell’Itria, painted around 1578 for the Convent of the Poor Clares in Paternò, the Moncada family’s ancestral home. Although unsigned, the donation records confirm that the painting was executed by Sofonisba, probably with the involvement of her husband.

Five years into their marriage, Moncada was killed by pirates off the coast of Capri. Sofonisba, left in some difficulty, requested help from Philip and from her legal guardian, her younger brother. During the sea journey back to the Italian mainland with Asdrubale, events took a surprising turn. Sofonisba formed an attachment to the ship’s young Genoese captain, Orazio Lomellino. Despite opposition from her family, and without the consent of her royal patron, she married him. Her Spanish allowance, however, continued to be paid. The couple settled in Genoa, where Sofonisba surrounded herself with a new circle of artists and writers, including Luca Cambiaso, the leading painter in Genoa. The city would remain her home for more than thirty years. Only in extreme old age did she return to Palermo, where, her eyesight steadily worsening, she was unable to paint. Seven years after her death, on the day he believed to be her hundredth birthday, Orazio placed an inscription on her tomb: ‘To Sofonisba, my wife … who is recorded among the illustrious women of the world, outstanding in portraying the images of man … Orazio Lomellino, in sorrow for the loss of his great love, dedicated this little tribute to such a great woman.’

By the time of Van Dyck’s visit a year before her death, Sofonisba had become the textbook example of a woman painter. Most female artists who are known to have worked in 16th-century Italy were regarded in literary terms: the rhetoric of their achievements was as powerful as the actual work. The language of this praise was remarkably consistent. Sofonisba was eulogised for her personal charms as much as for her artistic excellence. She was noble, virtuous, virginal. It was thanks to these qualities that Vasari and others, such as the Spanish priest Pedro Pablo de Ribera, could classify her as a ‘virtuosa’ and a prodigy. Gian Paolo Lomazzo and Filippo Baldinucci asserted that her ‘portraits after nature’ were second only to those of Titian. The value placed on Sofonisba’s work was inextricable from the fact of its creation by a member of the lesser sex.

At the same time, it was subtly demeaned, because while women like Sofonisba were diligent and accurate, capable of recording what they saw around them, they could never be truly inspired or inspirational. According to these narratives, Sofonisba’s art was always a form of accomplishment. It wasn’t strictly work, nor was it a vocation, so it had to be fitted into the rhythms of court and family life. The innovative painter from Cremona morphed over the years into a slightly elevated version of what critics have for centuries viewed as the ‘lady copyist’.

Linda Nochlin’s essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ (1971) was written partly out of a desire to deal with this issue of women artists as dilettantes. She concluded that no manipulation of the evidence or discovery of more ‘modest if interesting and productive careers’ could alter the statement of fact. But the interesting question was ‘why’. Her argument that women’s exclusion from academic training and study of the nude meant that they couldn’t possibly develop along the lines of male painters is especially true of the High Renaissance. Scholars of the period are confronted with the difficulty of ‘discovering’ women artists, since their very participation was contested, and risk falling into the neo-Vasarian pattern of celebrating prodigies. How do we value correctly the role of amateurs? It’s not surprising that the historian Joan Kelly asked: ‘Did women have a Renaissance?’ After nearly half a century of study, it is evident that the answer, for the most part, remains no.

Nochlin’s article led to a series of academic studies and exhibitions – including Women Artists: 1550-1950, which she co-curated with the Baroque specialist Ann Sutherland Harris – examining the careers of women artists from early modern Europe. These have included Sofonisba; Caterina van Hemessen (1527/8-66), who preceded her in Spanish court circles; the Florentine nun Plautilla Nelli (1524-88); the Bolognese painter Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614), joint subject of the Prado exhibition; the Antwerp history painter Michaelina Wautier (1617-89); and, most celebrated of all, Artemisia Gentileschi, to whom the National Gallery is devoting a major monographic exhibition this autumn. The result has been to demonstrate that the artists whom Nochlin identified as ‘modest’ in 1971 are far more significant than they first appeared. In the case of Sofonisba, it is not that her work is mediocre. Rather, we have asked the wrong questions of it and judged it according to criteria that denigrate what she was trying to achieve.

On the face of it, Sofonisba’s range is extremely restricted. There is little beyond portraiture, and only four works that are not connected to direct observation. Almost all her known paintings date from the first forty years of her life. Yet she worked outside the categories that defined artistic practice in her lifetime. There was no widespread tradition of self-portraiture in 16th-century Italy, despite the fact, as Michael Cole writes, that it is often seen as a defining feature of Renaissance art. Sofonisba made more images of herself than any other artist in the century between Dürer and Rembrandt. These paintings are among the very first examples of an artist systematically portraying themselves and using the images as calling cards. There is nothing flashy about them: most are small works and she depicts herself with extreme humility. She almost invariably wears simple (but expensive) black, although entitled, as a young unmarried noblewoman, to dress in rich embroidered fabrics. She doesn’t avert her eyes, however, but meets our inquiry as an equal. In an astonishing self-portrait (accepted as her work by most scholars, although not by Cole), which shows her having her portrait painted by her teacher Bernardino Campi, it is Sofonisba who dominates. Campi appears smaller and less significant than his illustrious pupil.

Her paintings of her family are also pioneering. Sofonisba was one of the earliest artists to advance work that valued family life, kinship and private history. The Chess Game, in which she depicts a servant with as much attention and affection as her three sisters, is interpreted by Cole as a friendship portrait, as remarkable in its way as Raphael’s painting of Agostino Beazzano and Andrea Navagero. The Portrait of Minerva, Amilcare and Asdrubale Anguissola shows a father’s love for his children, but also the different status of girls and boys in Renaissance families. Amilcare shields his daughter with his knee and torso, while turning his attention – and more obvious affection – to his young son, whom he embraces. It’s a depiction of what in Sofonisba’s case was a complex relationship with male authority. In Sofonisba’s Lesson, Cole makes a strong case for Sofonisba being one of the most significant artists of the 16th century. Her work, he argues, and her career, challenged received ideas about what it meant to be an artist and made it acceptable for women – if their male guardians permitted – to devote themselves to painting.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.