For more than two hundred years there was a megacity in Japan that almost no one from outside the country had ever seen. Edo, capital of the Tokugawa shoguns, began as a minor castle town around 1600 but grew rapidly after the Tokugawa dynasty demanded that around 250 feudal leaders establish estates in the city. Commerce flourished thanks to their conspicuous consumption. By 1720, Edo had a population of more than a million, making it probably the most populous city in the world. Yet practically the only Europeans to have visited it were a handful of Dutchmen – and so it would remain until the mid-19th century. No foreigners were permitted to live or trade on Japanese soil except the Dutch and Chinese, who were confined to enclaves in the port of Nagasaki, 750 miles from Edo. No Japanese were permitted to leave: those who disobeyed did so on pain of death.

These restrictions on travel and commerce, first imposed in the 1630s, are known as sakoku, or the ‘closed country’ policy. Closed Japan and its hidden megacity inspired fascination. The eyewitness account of Engelbert Kaempfer, a German doctor who joined the Dutch embassies in the 1690s, became a bestseller, cited by Kant and Goethe. Later accounts by Carl Peter Thunberg and Phillip Franz von Siebold kept curiosity alive. But since no one else could go, Westerners continued to depend on sources that were decades out of date. Then, just as Edo opened its doors, it changed its name and began a rapid transformation into what was, in many ways, an entirely different city. Matthew Perry of the US navy, whose gunboat diplomacy in 1853 forced the Tokugawa shogunate to admit American ships, never himself managed to set foot in Edo. But his aggression began the final unravelling of Tokugawa rule. The Meiji regime, which replaced it in 1868, renamed the city Tokyo. Edo would remain a place of the imagination.

It is tempting to draw a straight line from Edo’s early modern mystique to Tokyo’s popularity today. Before the pandemic shut down international tourism, Tokyo was one of the most visited cities in the world. But it hasn’t always been considered an appealing destination. The American archaeologist Edward Sylvester Morse, one of 19th-century Japan’s most sympathetic observers, described the cityscape as ‘dull and monotonous’. Even in 1919, by which time it was a regular stop on steamship tours of the Far East, Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire warned readers that Tokyo had few of the charms of other oriental capitals. There was nothing for foreigners to do at night, it noted, and nothing good to eat.

Foreign accounts give us little sense of what life in Edo was actually like. Kaempfer can’t tell us much. For most of his stay, he and his fellow ambassadors were locked up at Nagasaki House, the government lodgings built especially for them, waiting to be given an audience with Shogun Tsunayoshi. When they finally saw the castle they were shown only a few apartments. The real spectacle that day was not the grandeur of the palace but the Dutch themselves, who were brought before the shogun and made to perform what Kaempfer called ‘monkey tricks’. Sitting behind a screen, Tsunayoshi had them ‘now stand up and walk, now pay compliments to each other, then again dance, jump, pretend to be drunk, speak Japanese, read Dutch, draw, sing, put on [their] coats, then take them off again’. It was, as Timon Screech writes, ‘an anthropological exercise’. The encounter belongs to a long history of mutual ethnography between Easterners and Westerners.

Although we are lacking European accounts, the people of Edo themselves left a rich archive. The city had a highly literate population; it was also home to the artists Hokusai and Hiroshige. Amy Stanley’s Stranger in the Shogun’s City draws on this archive to pose the question: what was Edo like to a woman from the countryside, arriving in the city alone and almost penniless? Her answer is based on the letters and family records of a woman called Tsuneno, who came to Edo from the snowy northern province of Echigo in 1839 and lived there until her death in 1853 at the age of 49. Tsuneno’s Edo was a place to make a new beginning – but it was also dangerous, alienating to outsiders and a source of disease. Stanley describes backstreet tenements, pawn shops and pedlars, famines and rice riots.

But Edo was also the shogun’s city, and considering Tsuneno’s modest station she moved surprisingly close to the halls of power. On responding to an advertisement at an employment office, she went from backstreet penury into maid service for the family of a shogun’s bannerman whose estate was just outside the castle. The master of the house had direct access to the shogun, something the Dutch ambassadors never enjoyed. But the work was brutal and Tsuneno walked out after a few weeks. Not long afterwards, she was waiting tables in a working men’s canteen in Shinjuku; then she went back into service, this time in the house of one of the city’s magistrates. Like a Dickens character, she was carried on the uncertain currents of urban life into the company of both the lofty and the lowly.

The castle itself remained at a remove, the shogun shrouded in mystery. Sumptuary edicts maintained samurai privilege and a strict social hierarchy through minute regulations of housing, dress and behaviour. Yet Tsuneno’s story shows that elite and plebeian, rich and poor, often lived cheek by jowl, and commoners were far from cowed by their samurai superiors. Many samurai wound up in poverty themselves. Stanley relates a scandal in which a samurai was found to be running a brothel with a commoner woman to augment his meagre income. There is also an account of commoners jeering and throwing stones at the house of a discredited councillor, a hated figure who had once been the most powerful member of the shogun’s government.

Tsuneno, alienated from her family in the countryside but never completely disowned, survived four marriages and one apparent rape. It’s rare to read an Edo life history of such depth and intimacy, despite the wealth of surviving records. There was no shortage of wits and social satirists in Edo society but there were few great diarists. Most of the diaries we have are more like account books or laconic registers of the comings and goings of a household. Often they were written by more than one person. Literate Edoites chose to convey their feelings in the seventeen syllables of haiku or the 31-syllable tanka poem.

Tsuneno had years of troubled exchanges with her family. In the letters Stanley has uncovered, these characters emerge in all their complexity. In places, however, the record is reticent. At one point, Stanley speculates about a couple’s ‘workable, durable marriage’; elsewhere, she imagines a housewife’s fantasies of freedom from drudgery. But neither Tsuneno nor other letter-writers in her family recorded such private thoughts. There is a limit to what we can know.

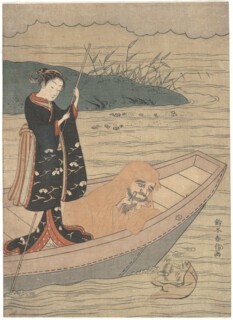

Screech, an art historian, looks at Edo as it was imagined and represented in art and poetry. He analyses vistas of Nihonbashi, the bridge at the city’s centre, discusses the iconography of power in palace interiors and the screen paintings on the walls, provides readings of landscape poetry, and divines the symbolic and geomantic meanings of various sites – major temples, samurai estates and the castle itself. One chapter focuses on the famous licensed prostitution district of Yoshiwara, on the northern outskirts of Edo, describing the way art and literature reveal the profane reality of the sex trade along with intimations of Buddhist enlightenment. In an iconoclastic print by Harunobu, for instance, an elegant maiden pilots a boat upstream while her passenger, the Zen patriarch Bodhidharma, gazes anxiously at his reflection in the water.

Harunobu’s image exemplifies a device in Edo art known as mitate, a form of allusion or parody. Mitate takes something iconic – even sacred – and transposes it to another setting, often one quite mundane. Edo was rich in examples of mitate, not only in irreverent popular prints. As Screech shows, many of the major religious sites sponsored by the Tokugawa dynasty ‘both mimicked and replaced’ counterparts in the old capital of Kyoto, seat of the emperor, whose sacred rule conferred legitimacy on the secular shoguns. Kan’ei-ji, the temple where six Tokugawa shoguns are buried, modelled itself on Enryaku-ji, which had guarded Kyoto since the eighth century. A miniature replica of Kyoto’s Kiyomizu Temple – celebrated then as now for its high balcony and impressive view – was installed on Kan’ei-ji’s grounds. Even Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest freshwater body, was replicated in miniature in Edo, together with an imitation of its island shrine. The appropriations announced that the shogun’s city possessed all the sacral gravitas of its ancient rival.

Edoites enjoyed comparing their city to others. Not to the cities of Western Europe, of course, but to those in the western part of the Tokugawa realm: Kyoto, residence of the emperor, and Osaka, the capital of commerce. A consumer culture flourished in all three cities. In the 1830s, Kitagawa Morisada, an Osaka native living in Edo, began compiling an encyclopedia of manners and customs in the cities of Japan. Between the cities of the east and those of the west he noted distinct fashions in food, hairstyles, umbrellas and tobacco pouches, house construction and festival decorations. Eastern and western Japanese urbanites wore different colours of underwear. Even their public toilets were different. Morisada’s Miscellany, which ran to thirty volumes over thirty years, was the encyclopedia of a modernity invisible to Europe.

In both Screech’s and Stanley’s portraits, Edo is a world city – not just world-class in size but connected to world trends and events. This perspective accords with the current generation of writing on the Tokugawa policy of sakoku. Scholars once viewed Japan’s closure as absolute, draconian and costly to its people. Watsuji Tetsurō’s Sakoku: Japan’s Tragedy, published shortly after the Second World War, became the founding text of this school. Watsuji argued that Japan had cut itself off from the world just at the moment when scientific inquiry was blossoming in Europe, a mistake that would leave it two centuries behind. A ‘lack of scientific spirit’, he believed, explained Japan’s wartime defeat. American historians reinforced his line by portraying Commodore Perry’s ‘opening’ of Japan as the collision of a dynamic, youthful United States with conservative Tokugawa Japan. Yet in the decades after Watsuji’s book appeared, as Japan recovered from the war and its economy became globalised, sakoku was re-examined. Historians since the 1970s have shown that Tokugawa Japan was never as isolated as the term implied. Diplomatic relations were carried off amicably – if infrequently – within the East Asian regional order. A broad range of commodities were traded, not only with the Asian continent but with the Ryūkyū islands to the south of Japan and the indigenous Ainu people to the north. Western works on anatomy, optics and engineering were translated and interpreted by scholars of what Edoites called ‘Dutch studies’. Edo artists depicted the first manned hot air balloon flight in 1787, not long after the Montgolfier brothers lifted off in Annonay.

Both Stanley and Screech barely mention sakoku, since the notion of Japan’s seclusion is now so widely dismissed. Screech’s Edo is a city full of imported exotica: the European paintings collected by Shogun Yoshimune in the early 18th century, the Chinese-influenced Obaku Buddhist temple in Asakusa, an ‘international Buddhist site’; even the Nihonbashi bridge, which shows signs of ‘external input … likely to have been European’. The ukiyo-e woodblock prints that began to appear in the second half of the 18th century ‘attest to a new sense of Edo’s place in the world’. These are provocative claims even to readers accustomed to the historiographic turn away from sakoku.

Stanley presents Edo as globalised in a different sense, by interspersing references to events elsewhere in the world – and forebodings of gunboats – throughout Tsuneno’s narrative. There were riots in Edo, she notes, at the same time as the French Revolution. Reflecting on the fortunes of Edo samurai, in decline in the 1830s, she reminds us that within two generations the samurai class would be gone. American whalers and clippers in the China trade passed with increasing frequency through Japanese waters. ‘During the years of Tsuneno’s childhood,’ she writes, ‘the world was coming closer all the time.’ The darkest cloud on the Tokugawa horizon appeared in 1842, with news of Qing China’s defeat in the First Opium War. The austerity measures enacted by the government shortly afterwards were in part a response to a sense that coastal Japan was equally vulnerable.

None of these events touched Tsuneno directly. News of the Opium War circulated among samurai but, as Stanley points out, ‘Tsuneno, if she ever knew, would not have cared.’ This juxtaposition of world events with the life of someone oblivious to them has a peculiar effect. Tsuneno died in the summer of 1853, two months before Perry’s arrival, but in Stanley’s account they somehow seem destined to be brought together. It’s an appealing novelistic device but it doesn’t tell us much. An argument could be made that inexorable forces brought Perry to Japan’s shores in 1853, but those forces had little impact on Tsuneno’s life, which would probably have unfolded in much the same way had she lived one hundred years earlier.

This brings us back to the question of sakoku. The effort to situate Edo in the world, either by emphasising its connections to Europe or by situating the city’s history in a global chronology, suggests a reluctance to let Edo be what it was: a city ruled by a domestic logic that largely existed on its own terms. Developments in Europe did feed the curious intellects of Edo artists and scientists, and threats from abroad would ultimately unleash radical ideas at home, bringing down the Tokugawa shogunate. But for two and a half centuries the Tokugawa ban on trade had a profound impact on Edo. It allowed the Tokugawa family to maintain peace through a careful balance of power among rivals. Did the people of Edo need the rest of the world? The Tokugawa realm – tenka, ‘all under heaven’ – was large enough to contain multitudes, from the artistic output of Hokusai to the tumultuous life of Tsuneno.

The now unfashionable term sakoku first appeared in a Japanese translation of Kaempfer’s History of Japan published in 1801. As an appendix the translator included an essay Kaempfer had written under the prepossessing title ‘An Inquiry, whether it be conducive for the good of the Japanese Empire, to keep it shut up, as it now is, and not to suffer its inhabitants to have any Commerce with foreign nations, either at home or abroad’. Kaempfer begins the essay by asserting that God had made the Earth ‘to be common to all’ and that to shut off one country was an outrage against nature. But then he reverses his argument: Japan is blessed by nature and wise government, and needs nothing from beyond its borders. The country is ‘populous beyond expression’, and Edo, ‘the Capital of the whole Empire, and the seat of the secular Monarch, is so large, that I may venture to say, it is the biggest town known’. Its citizens live in peace and comfort. Kaempfer, who came from a Germany torn by wars of religion and feuds between petty baronies, saw an impartial and absolute sovereign as the surest guarantee of tranquillity. Despite the ‘monkey tricks’ Tsunayoshi had had him perform, the shogun impressed him as just such a sovereign. ‘Their Country was never in a happier condition than it now is,’ he concluded, ‘governed by an arbitrary Monarch, shut up, and kept from all Commerce and Communication with foreign nations.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.