On 11 November 1855, a massive earthquake and tsunami destroyed most of Japan’s capital city, Edo, the precursor of modern Tokyo. Roughly 7000 people were reported dead or injured, and the numbers rose in the days that followed. There were no newspapers published in the city – the shogun’s government forbade public comment on anything directly concerning the regime – but by the end of the year hundreds of woodblock broadsheets had appeared with stories and interpretations of the disaster. Among the surviving broadsheets one type stands out: colour woodblock prints depicting the earthquake as a catfish.

Since the 17th century, folklore had associated catfish with earthquakes. It was said that a giant catfish lay under a stone at the Kashima shrine, close to the easternmost point of Honshu, Japan’s main island (nearby present-day Narita Airport). The god of the shrine had the duty of holding the catfish down. When he neglected his job, the catfish would wake up and shake, causing earthquakes. The god of Kashima seems to have been peculiarly negligent around this time: an earthquake destroyed the castle in the city of Odawara in 1853, another struck near the imperial shrine of Ise in the summer of 1854, and two tsunamis caused thousands of deaths along the Pacific coast that autumn. These events occurred soon after the arrival of American gunships under Commodore Perry forced the shogunate to open its ports to trade, rocking a dynastic system that had maintained stability in Japan for 250 years. It is not surprising that many in Edo believed the gods had chosen this time to overturn the existing world and start things anew.

The first catfish prints appeared within two days of the earthquake. They depict the catfish in a wide range of guises, sometimes as big as a whale, sometimes human-sized and anthropomorphised. Despite its place in legend as the source of the destruction, the catfish was not uniformly presented as malevolent. In some prints, catfish rescued victims from ruined houses or helped in the reconstruction. Other prints were satirical, even though they were made at a time when the dead and injured weren’t fully accounted for and thousands of people were still without housing. I have been showing these pictures to students for years, interested in what they tell us about the period, but until the earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan on 11 March it had never occurred to me just how remarkable and strange to modern sensibilities this outburst of satirical humour in the face of disaster was.

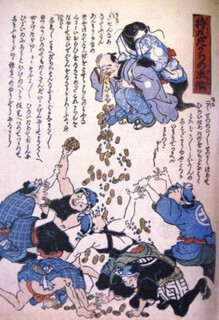

The example reproduced here, ‘Mr Moneybags Launches Forth His Ship of Treasure’, employs a common motif: the suffering of elite merchants and the delight of working men. The man at the top is a wealthy miser: with the encouragement of a catfish, he is vomiting gold coins. Three men wearing the blue leggings, jackets and cloth headbands of craftsmen and builders scramble for the fallen money. The catfish lectures the miser: ‘Sir, you suffer now because you oppressed those beneath you in ordinary times. It would be well for you to change your ways and practise charity and virtue.’ Meanwhile, one of the labourers tells his mates: ‘Don’t be greedy. If you save too much and an earthquake comes you’ll regret it: better to go and spend it at the temporary brothels and keep it circulating.’ Destruction of property naturally hurt the haves more than the have-nots, and construction workers in particular stood to profit from the city’s rebuilding. Indeed, just as many occupations seem to have profited as suffered in the aftermath of the earthquake.

Another print depicted two groups of people standing on either side of a catfish, one labelled ‘those who laugh’ (a carpenter, a plasterer, a lumber merchant, a roofer, a blacksmith, a prostitute, a physician and a street-food vendor) and the other ‘those who weep’ (a teahouse proprietor, a seller of eels, a seller of luxury goods, a diamond dealer, an import merchant, musicians and entertainers). A city made entirely of wood, paper and clay could be rebuilt in a matter of weeks, and reconstruction provided work at good wages to a large segment of the urban population. When working men had spending money, street trades like prostitution and fast food profited too.

Although Japan’s disaster-prone capital lies on a major faultline and tremors are frequent, fire was by far the more common source of destruction in the 19th century. A conflagration that turned several blocks to ashes occurred in Edo on average every five or six years. Fires occurred most frequently in the dry winter months. Instead of attempting to extinguish them with water, firefighters sought to control the flames by demolishing or stripping buildings along the flanks of the blaze and leaving it to burn downwind towards open fields or the bay to the east of the city. Since there was a seasonal rhythm to these events and the gap between them was short, Edo’s citizens learned to flee, then return and rebuild. They kept their belongings light and portable and lived in houses that were easily dismantled. In 1880, a fire swept through Kanda’s city centre, destroying 16 blocks of dense tenements and displacing 5986 people. The mayor reported that, fortunately, it had occurred during the day, so there were no deaths or injuries. With a population well prepared for disaster, destruction of property even on this scale was accommodated within the management of the city.

This accommodation was possible because the city’s light physical infrastructure was matched by a strong and enduring social infrastructure. The people of Edo policed themselves and fielded their own fire brigades. The wealthy property owners who had the most to lose from lawlessness and property damage paid directly for these services, which were provided by their tenants and employees, and established town residents provided alms to the poor until houses were rebuilt. Although this charity was in theory voluntary, the need to maintain neighbours’ respect (and keep their custom) made it effectively obligatory. After major disasters such as the earthquake of 1855, registers were compiled in each neighbourhood listing the names of donors and amounts given, making the contributions a matter of public record. Kitahara Itoko, Japan’s leading historian of disasters and the author of a social history of the 1855 quake, has found that the donations corresponded closely to the wealth of each household, with the city’s wealthiest merchant houses, like the Mitsui dry goods business, contributing more than a thousand gold pieces, while smaller shops contributed as little as a few coppers. The shogun’s government made a practice of rewarding almsgivers after disasters, but the same fixed amount was doled out to everyone on the register, so that the compensation was little more than a token to the wealthy but could be double the amount of the original donation in the case of a poor household.

The working man gathering Mr Moneybags’s treasure implicitly referred to a physiological theory of cycles in nature, of destruction followed by renewal. Like typhoon-season floods and dry-season fires, earthquakes and tsunamis were understood as corrections of temporary imbalances in the vital force perpetually flowing through the world (known in Japanese as ki and in Chinese as qi). Periodic eruptions of natural violence released pent-up force and kept both nature and human society healthy by renewing them. In a study of the catfish prints, Gregory Smits has shown that Confucian philosophers as well as ordinary people believed that the economy followed the same principles. Just as ki flowed continuously in nature, money should be kept moving in the economy too, not allowed to stagnate and foster greed. For this reason, many people viewed capital accumulation distrustfully. Nature, they believed, censured it.

It would be a mistake to presume that these Japanese fatalistically accepted natural destruction. Other contemporary accounts reveal that Edoites mourned the loss of family and friends, that they commemorated their deaths solemnly and sought solace in religion. But the relief of having survived, the outpouring of private and public charity, the break from everyday life and its duties, the levelling effect of the shared crisis, and the economic activity and opportunities in the reconstruction that followed, gave a positive tone to many of the catfish prints, prompting Kitahara to coin the term ‘disaster utopia’ to describe the world they depict. Of course, the condition was temporary, and neither alms nor higher wages were sufficient to cause a fundamental change in the poverty of the masses in the city’s tenements. Nevertheless, since everyone suffered together, and practically everyone contributed alms to relieve that suffering, common folk could believe that nature – in the form of the trickster catfish – had indeed instigated a healthy social renewal, and that these were bright times. Many of the prints plainly celebrate the present: using a formulaic phrase containing equal measures of irony and genuine hope, they call it ‘this blessed age’.

Why aren’t the Japanese celebrating today? If the Fukushima nuclear plant can be brought under control, post-disaster reconstruction, at least in the long term, holds out the possibility of social and economic renewal. Assistance is flowing into the tsunami-affected region, voluntarism is flourishing and there is talk of this being an opportunity to revitalise the country, evoking notions of economic stagnation and flow that Japanese would have readily understood 150 years ago. Yet a wide gulf separates the Japan of the mid-19th century from the Japan of the present. In its slow unfolding and the inequality of its social effects, March’s triple disaster may bear more resemblance to a premodern famine than to the earthquake-tsunami that destroyed the capital in 1855. No one ever welcomed a famine because of its potential for enabling renewal. The drawn-out disaster gradually exposed and exacerbated class and regional disparities. The tsunami also brought to the surface deep structural problems: the depopulation of rural areas and the advanced age of their inhabitants (the median age of tsunami victims was reportedly around 70); the economic fragility of Japanese farming, which depends on government subsidies and tight import restrictions; and the fragility of the food system, vulnerable as it is to the invisible threat of contamination.

Nuclear fears were a key issue in the nationwide local elections of 10 April, but seeking stability voters turned to incumbents. The list of anxieties for people in Japan is long: how bad will the situation at the Fukushima nuclear power station get and when will it be resolved? What should one believe among the experts’ conflicting reports? When will the aftershocks end? And the blackouts? Will the towns along the Tohoku coast be rebuilt? Will the nuclear evacuation zone be inhabitable, and will food from the region be safe? In Tokyo one of my former neighbours, a woman in her sixties, writes of ‘trains running on reduced schedules, blackouts and calls to save energy, shops half dark, heat off in the house – why, we lived this way just a little while ago. I can only hope this will be the turning point away from mass production and mass consumption, towards a sustainable society.’ For people like her, who remember the days before Japan’s economic take-off, the hope is that this disaster will lead to a reduced dependence on heavy technological infrastructure.

It is remarkable that a country so seismically active and vulnerable, and which had developed the art of light infrastructure, should have embraced nuclear power. Japan began building heavy in the 1870s, soon after the modern state that replaced the shogunate chose to join the international economic and military competition led by the Western imperial powers. The country’s first model factory, a silk filature built under French guidance, and its first planned commercial district, the main avenue of Ginza in central Tokyo, were both constructed from brick in 1872. A massive earthquake in central Honshu in 1891 damaged iron bridges and toppled brick buildings, sparking debate over the appropriateness of Western technology to Japan, and the possible superiority of the lightweight, flexible structures that carpenters had built there for centuries (Gregory Clancey’s brilliant book Earthquake Nation explores the cultural politics of this debate). The debate would continue into the era of nuclear power. Today, Tokyo’s skyscrapers are built with flexible frames, designed to sway in earthquakes. Yet nowhere have architects been able to match the light and quickly constructed urban fabric that Japanese artisans had perfected before modernisation.

So many Western journalists have written recently of the long shadow cast by Japan’s status as the only country to have been attacked by atomic bombs. Yet it is striking how little the media in Japan have referred to Hiroshima and Nagasaki since the perilous condition of the Fukushima plant became known. Nuclear fears were galvanised into a mass movement for the first time not by wartime trauma but in 1954, when fallout from an American hydrogen bomb test in the Bikini Atoll rained on Japanese fishing vessels, ultimately resulting in the death of a radio operator and yielding news of irradiated tuna, which led to the disposal of nearly 500 tonnes of fish. It was the uncertain threat of nuclear fallout rather than the certain horror of the bombings that awakened public anxiety. In this respect, the Japanese public differs little from many Western European societies, wary both of American power and of Big Science and distrustful of their own governments. The Japanese government has frequently earned people’s distrust, through corruption scandals as well as through obfuscation during crises threatening public health, including nuclear accidents in 1995, 1997 and 1999.

The Japanese national legislature approved the budget to establish a nuclear power industry in March 1954, just days after the Bikini Atoll test, when the effects of the fallout hadn’t been recognised. Japan’s first reactor, based on British technology, began operation in 1965. Japanese preparations had been supported by the US Atoms for Peace programme. Anxious about the damaging effect the anti-nuclear movement might have on relations with the United States, the pro-American newspaper Yomiuri launched a national campaign in the 1950s to tout the benefits of nuclear power, reasoning that the best antidote to fear of the bomb was the popularisation of nuclear science. Japan’s most famous horror film, Godzilla, and its first television cartoon series, Astro Boy (known in Japan as ‘Iron-Arm Atom’), mark the poles of public sentiment in this early period of nuclear power. Godzilla, made in late 1954 in direct response to the Bikini incident, depicts a monster born of the hydrogen bomb who breathes radioactive fire. But it also shows Tokyo being saved from destruction by a heroic nuclear scientist. Astro Boy, the first episodes of which were shown in 1963, presents a benign and cute nuclear-powered robot, looked after by a lab-coated doctor from a fictional Ministry of Science. Despite the closeness of the Cold War nightmare of nuclear armageddon in the 1950s, the Japanese public seem to have followed the search for domestic sources of uranium with enthusiasm. Hot spring spas even advertised the benefits of the radium in their waters.

The greatest expansion of Japan’s nuclear industry took place after 1973, when Opec’s oil embargo sparked widespread panic-buying and hoarding in Tokyo. The oil crisis presented Japanese authorities with the problem of managing public fear. Their response was to order the construction of more nuclear facilities, providing the illusion – if not the reality – of greater energy security. Nuclear power is the quintessential heavy infrastructure, a physical embodiment of what Ulrich Beck has called the risk society, a society in which the greatest hazards are of human manufacture, and their threat comes ‘clad in numbers and formulas’ rather than in more tangible form. The technologies of the risk society, maintained by the state, lead to a battle over information. Questions about the worst-case scenario plague the minds of residents in the Tokyo-Yokohama conurbation today, and a desire for information makes people listen obsessively to the news conferences held several times a day by the prime minister’s office and by Tokyo Electric. The authorities’ strategy has been to provide masses of data but no longer-term assessments. As the sociologist Eiko Ikegami recently observed, the Japanese style of bureaucratic rule, which places internal consensus above transparency, has proved poor at responding to crises; but if a government spokesman were explicitly to state the worst-case scenario, no matter how low he might assess the scientific probability of its occurring, the announcement could create unmanageable panic. No country has the capacity to evacuate an urban area with more than 30 million residents.

Reports in the Western media since 11 March have emphasised Japanese stoicism and resilience. But these aren’t innate national characteristics. Much of the stoicism derives from the collective memory of past privation, particularly during and after the Second World War. In the small farming and fishing settlements lining the Pacific coast north of Tokyo, traditions of village or neighbourhood self-government, stretching back to a time when the feudal authorities extracted taxes collectively, are still reflected in local solidarity, particularly among older residents. Neighbourhoods in Japanese cities were once organised similarly.

One can find the vestiges of traditional community even in Tokyo, in places like the downtown neighbourhood where I have lived on and off for the past 25 years. Although the main streets there are now lined with high rises, two-storey wooden houses, tightly packed in, dominate the side streets. Many residents have known one another for decades, greeting one another each morning, sharing tasks like taking deliveries or carrying out the rubbish, and hearing one another’s family spats. Even the ubiquitous convenience stores on the main street, seen by many as the emblems of a deracinated urban lifestyle, are often franchises managed by locals who formerly owned corner shops. Much has been made of the absence of looting after the recent earthquake and the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, but few residents of Japan find this remarkable: people don’t loot from neighbours they say hello to every morning. Something of traditional local practice is evident after fires, which today have become rare. When I was living in Tokyo in the mid-1990s, a house across from my apartment that had been used for storage by a local fishmonger burned down. The next day, the shopkeeper came around with a gift, apologising and thanking me for my assistance, although I had done no more than run out into the street to watch the municipal fire fighters handle the blaze. I am sure the shopkeeper made the same visit to everyone else on the block: it was a ritualised affirmation of neighbourly obligations, like the giving of alms.

Despite this, it’s true that neighbourly ties in Japan are increasingly attenuated. In preindustrial society, the strength of local community derived from force of circumstance: strong social infrastructure was a survival strategy in a volatile natural landscape. When Japan began building heavy physical infrastructure, technology brought with it new costs: unbounded and unpredictable environmental risks, an opaque technocracy and a public dependent on that technocracy yet unable to trust it. In this respect Japan today is no different from any other advanced state. But in a country that prides itself on maintaining its unique traditions while at the same time marching in the vanguard of industrial modernisation, what was forfeited comes into sharper relief: a mode of urbanism that allowed ordinary people to build and rebuild their cities and towns themselves. Invocations of national solidarity are common in times of crisis; we have seen them in the Japanese media and in a rare address from the emperor to the nation. But the strength of local community in Japan derives from other sources. The strong social infrastructure that has been a tradition there should not be thought of as separable from the light physical infrastructure that once accompanied it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.