Sometimes another world is there – you glimpse it out of the corner of your eye. In 1965 an engineer called Ivan Sutherland – he had effectively invented the whole field of computer graphics by writing a program called Sketchpad which allowed users to draw directly onto a screen – had a vision of the future. ‘The ultimate display,’ he wrote in a conference paper,

would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter. A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal. With appropriate programming such a display could literally be the Wonderland into which Alice walked.

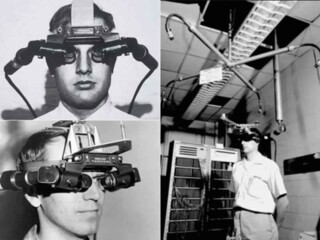

Quite a vision, at a time when most computers still depended for input and output on punched paper tape. Three years later, in 1968, Sutherland built a machine at MIT he called the Sword of Damocles: a big stereoscopic display – so heavy that it was hung on an arm suspended from the ceiling before being attached to a person’s head – that magically inserted virtual objects into the wearer’s field of view. The technology was so new and unfamilar that it was twenty years or more before it was even given a name; the term eventually settled on was ‘augmented reality’. These prototype AR objects were simple wireframe structures – glowing lines of translucent white – but the machinery inside the Sword was clever enough to track the head’s movements, so that even as you looked to the side the 3D construct remained hoveringly in place.

But Sutherland wasn’t interested just in conjuring up visual diversions. He was an acolyte of the indefatigable Vannevar Bush, wartime head of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development, the department that brought us radar and the atom bomb, who in an article in the Atlantic in 1945 had his own encouraging vision of a better future: one in which an ordinary person sitting at their desk would – thanks to advances in storage and technology – be able to summon up with the merest click of his fingers all ‘books, records and communications’ he had filed away at any point in time and consult them ‘with exceeding speed and flexibility’. Take this further and you start to imagine the complete contents of the world’s copyright libraries, the combined collections of the Prado, Met and Louvre, every piece of recorded music, every photograph, every film, all instantly retrievable by the person at their desk: the dream of infinite knowledge. What Sutherland realised was that in order to realise this dream it wasn’t enough to develop a capacious filing system and efficient method of retrieval – hell, he’d have thought the internet wasn’t enough, even before it was invented. No, you needed to be able to see and touch all the knowledge you’d summoned, bring it into the here and now: open that book, watch that movie, hear that music all around you. You needed to be able to insert that other world into your own. It’s a dream that’s still – just – around the corner. Imprisoned at your desk still, or stuck on a moving train, what would it be to be able to view whatever information you liked, retrieved from whatever point in time or space, displayed for real before your eyes?

All interfaces between humans and computers depend on metaphors of one kind or another. How to make sense of all the zeroes and ones if you can’t interpret them in real-world terms? In the years following Sutherland’s demonstration, researchers inspired by his sort of dream, many of them based at Xerox PARC in Palo Alto, invented not only the technology of interaction that’s second nature to us today – the mouse or other tool that manipulates objects on a screen – but the metaphors that lie behind the manipulation: the ‘window’ onto the world of information beyond, the ‘desktop’ on which there are ‘files’ and ‘folders’ you can ‘open’ or ‘archive’ or consign to the ‘trash’. The first public glimpse of that future, not too coincidentally, was also in 1968, at the autumn gathering of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (et al) in San Francisco, where – in what came to be known as ‘the mother of all demos’ – Douglas Engelbart of Stanford’s Augmentation Research Centre presented not only a prototype of the mouse, but also word processing, file versioning, videoconferencing and hypertext. The assembled computer scientists were in awe. But gobsmacking though this demonstration was, it was also – as visonaries like Engelbart probably realised then, as much as frustrated keyboard-bashers realise now every time their fucking file won’t save – only a shadow of the wilder dream: the one that Ivan Sutherland was just at that moment describing at MIT, the ultimate display that would magic these remote digital constructs into tangible reality in your very living room. From metaphor to matter.

Fifty years on: it’s been a long wait. And it’s a promise that remains always just beyond reach. For a while now, eager Apple-watchers with itchy fingers have been tuning in to the underground rumblings and rumours from Cupertino, where the folk who brought us the iPhone and Magic Mouse have been filing patents, hiring specialists and generally creating a buzz about the possibility of upcoming glasses – iGlasses, anyone? – that, being ‘designed by Apple in California’, as the sexy stickers say, won’t make you look like a total nerd if you wear them on the beach to augment your view of the world around you with … well, with whatever Apple and an army of nifty app makers have the ingenuity, resources and permission to provide. Information about the scene you’re looking at – expected opening time of that beachfront bar, signature cocktails, price of fish – that you’re too lazy to Google. Alerts from elsewhere – message from an absent friend, notice of a cancelled dentist’s appointment, news of the imminent collapse of the Dow – that at the moment you risk missing if you don’t happen to look at your phone for five minutes. If Silicon Valley & Co. had their way and could dissolve the world’s legislatures in order to overturn privacy laws that currently prohibit them from deploying their facial recognition algorithms to the full, you could be informed by your glasses that the stranger who is safely keeping her distance from you along the beach is actually that wunderkind from school, Alice, who once pooh-poohed your attempts to be clever and is now apparently an eminent palaeontologist living a dream life with an attractive oboe-playing husband and four attractive kids. (While we’re talking about dreams, you may feel that anyone being able to divine the identity of everyone they see is closer to a nightmare – but it’s only because it’s a nightmare and therefore illegal in most countries that it doesn’t happen already. In Russia anyone can use Yandex’s reverse image search to find someone’s name on the basis of only a picture, and in China – more benignly – Baidu has released augmented reality glasses that remind Alzheimer’s sufferers of the names of people they’re looking at.) If you think all this is gimmickry – first world luxury – you may have a point. But how can we know for sure, when no one’s yet tried on the specs? I, for one, still think it would be cool to be invisibly reading a book – any book of my choice – that only I can see.

If you haven’t been at least a bit excited about the possibilities then you haven’t been wowed by the showmanship of the new world’s prophets. Take the gleefully childlike entrepreneur Rony Abovitz, founder and CEO of a Florida-based augmented or mixed reality startup called Magic Leap, which secured $2 billion in funding from – among others – Google, Alibaba, the German publishing conglomerate Axel Springer and the Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund. While the money was pouring in, Magic Leap kept shtum in public about what it was actually working on except to say that whatever it was – glasses? goggles? head transplants? – it depended on a revolutionary ‘photonic lightfield chip’ that would produce 3D moving images more lifelike than anything we’d ever seen. A teaser video on a sparse website showed hundreds of giddy children gasping with delight as a huge white whale crashed through the floor of their high school gym. In a TED extravaganza in 2012, images of the revolving Earth and a robot wasp flashed up to the theme of 2001: A Space Odyssey as a pair of clowns in red and green monster suits pranced onstage to bow down before a giant bar of fudge. They were followed by Abovitz – if it was indeed he – in head-to-toe astronaut gear, who spoke only to declare the importance of an ‘ancient and magical keyword’, phydre, which turned out to be nothing more than the word ‘fudge’ transliterated into Greek. Abovitz, who is said to have grown up playing Atari video games, seemed to believe that for mixed reality to be compelling – for anyone to have a reason to want it – it had to tell a story. To help fulfil his dream, Abovitz hired the sci-fi writer Neal Stephenson as Magic Leap’s ‘chief futurist’. Magical creatures, the TED presentation seemed to suggest, would soon be prancing on your kitchen sideboard and the denizens of Star Wars would lurk behind the sofa: you’d be drawn in to an ‘always-on’ experience of (favoured buzzword) ‘immersive’ gaming that would seamlessly merge the fantastical and the mundane, so that your grey and humdrum life would suddenly spark with fireworks of glorious colour – like the moment in The Wizard of Oz when the Technicolor is flipped on.

But when Magic Leap finally released its prototype goggles – Magic Leap One Creator Edition, RRP $2295 – in the summer of 2018, the steampunk headset with bum-clip computer attachment curiously failed to ignite the joy of millions. Yeah, you might get to see a dancing bear or two and be able to skip tracks on a Spotify playlist represented by a picture floating in space before you, but really the all-singing, all-dancing alternate reality that the marketing teased had vanished in a puff of smoke. That’s what happens when you put your faith in a conjuror. Now Magic Leap has put aside its faery dream of sprites and pixies and – in what is euphemistically known in startup land as a ‘pivot’, which really means panicked U-turn – has started grubbing around for business contracts on more workaday uses of augmented reality, recently losing out to Microsoft on a $480 million bid to supply the US army with battlefield information-providing, thermal imaging-enabled AR headsets for combat and training purposes.

While Apple still toys around with its secret designs for glasses that your Uncle Bob will want for Christmas, it turns out that AR in its current form really only appeals to enterprise and industry customers. Take Boeing, for instance, which has equipped its technicians with AR headsets that superimpose the correct wiring diagrams on the electronics they’re working on and provide them with revolvable 3D models of a plane to help them figure out how each part fits into the whole. Nice for a company like Boeing: fewer mistakes are made, money is saved – but this is nuts and bolts stuff, not much fun for dreamers. The depressing truth about the state of the art of augmented reality is that current technology just isn’t up to the job of generating high-fidelity 3D images on the fly that accommodate themselves to the space around you without a hefty battery pack that would look frankly ridiculous suspended from your nose: this stuff requires a massive amount of processing power and a lot of bandwidth. This is one reason Apple is waiting: chip design isn’t improving year on year as significantly as it once was, and the 5G mobile networks needed to deliver fantastic imagery wherever you are haven’t yet been fully rolled out.

In imagining the ultimate display in 1965, Sutherland envisioned a computer-generated chair in your room that was ‘good enough to sit in’, and building or drawing or reproducing virtual objects in the actual space around us is still the fundamental aim of augmented or mixed reality, whether you see them through glasses, with a somewhat restricted field of view, or – eventually, inevitably, when the technology gets good enough – through contact lenses that would create the illusion that nothing stood between you and the displayed objects at all: the invisible screen. And, in yet a further iteration, you can imagine a future in which the world itself may be the screen: there’d be no need for the mediation of glasses or lenses if you could – as in Abovitz’s naughty hint of the far-far-off possibility of a computer-generated whale visible to the naked eye of everyone present – somehow display an actual object built of light that hovers in thin air, a figure you can walk around and nearly touch. In 2018 researchers at Brigham Young University, using lasers, developed a technique for trapping a single cellulose particle and moving it rapidly through the air while illuminating it with red, green and blue light: this ‘photophoretic trap volumetric display’, Nature reported, generated the illusion of a tiny butterfly flapping in the room. A summoned, living thing of this type has been a sci-fi dream ever since the image of a desperate Princess Leia was beamed into existence – ‘Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope’ – in the first Star Wars film in 1977. Displaying a book before your eyes is cool, yes – but projecting the image of a person into the very space around you is something else: a person from the other side of the planet, built from light.

But in a way the method of display is immaterial: the innovations we’re waiting for are really only about making the illusion increasingly persuasive. We can already display 3D objects in the space around us with nothing more than a recent-model smartphone: sofware developers can use augmented reality tools developed by Apple (ARKit) or Google (ARCore) to superimpose models of whatever they wish onto the scene captured by your phone’s camera. This was the trick that enabled the 2016 summer craze for Pokémon GO, which had hordes of grown-up people prowling shopping malls and parks on the hunt for Pikachus and Eevees. Surreptitiously, the big tech firms have been implementing previews of an augmented future on the devices we already carry. On an iPhone now you can install an IKEA app and see how an armchair or wardrobe looks in the corner of your actual room, or the Nike app and reward yourself with a pair of virtual trainers. Marketers love it, but the technology has virtuous uses too: an architect can display an explorable 3D model of a building or a city district on a client’s table; a teacher of medicine can show students a full-size representation of a cadaver or living body and isolate the liver, heart or spleen.

A digital body suspended in space: the future is already here. Designing the glasses that will make these simulations seem more immediate is, really, a trivial, technical problem: the serious obstacle to having virtual objects interact with real ones hasn’t been about the virtual world at all. The secret truth is that for the illusion to work properly, the device displaying them has to be able to measure and model the real world around you in order to calculate how and where the simulations will appear. Occlusion: the barking virtual pet you can summon into your presence by Googling ‘golden retriever’ on a newish Android phone has to be told whether to sit behind or in front of your pot plant or coffee table. Plane detection: if you want to hang a virtual picture or TV screen on your wall, your device has to understand where the wall is; if you want the floor of your room magically to turn into the floor of the Chauvet cave the machine has first to be able to find your floor.

It’s hard, measuring the real world, and replicating it intimately in digital form: to do it properly requires advanced sensors such as the lidar system in the latest iPad Pro, which uses a laser to scan the surfaces around it, and a lot of computer wizardry. The virtual part of virtual reality has been with us for ever – or at least since the 1790s, when Wordsworth complained that the crowds were too easily pleased by the room-sized illusions of exotic lands on view in the panoramas of Leicester Square. It’s the real part that’s where the fun is, and we’re nearly there. Any moment now you’ll be able to pop on your specs and have a look.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.