Nineteenth-century French art, and French artists, were fortunate to have the backing of some of the best writers of the day. Stendhal, Baudelaire, Gautier, Goncourt, Zola, Maupassant, Huysmans and Mallarmé all doubled up as art critics. (The bullish Courbet took on both tasks: doing the work and the self-promotion.) It helped that there were extraordinary new artists to support, as well as a hulking and immobile target to attack: the annual Salon. The Académie des Beaux-Arts organised it, controlled who and what was shown, awarded prizes and public commissions. The thousands of artworks were all for sale: this was, as Huysmans put it, an ‘official bazaar of art’, the ‘Stock Exchange for oils on the Champs-Elysées’, the ‘temple of Offcuts’ from ‘the state-run farms of the Academy’. It also controlled, both implicitly and explicitly, what and how a painter was expected to paint. There was an established hierarchy of subject matter: high solemnity and low sentimentality were applauded; imagination should be orderly; finish was preferred to vivacity. You could say that all Salon pictures were still lifes, even a picture of a heroic battle or a portrait of Victor Hugo – perhaps especially a portrait of Victor Hugo, whose marmoreal fame had turned him into a still life already.

This is not, of course, as simple or monumental a story as the professional insiders v. the excluded rebels. Artists, even the most rule-breaking, often enjoy acclaim just as much as diligent hacks: they want to offend but they also want to be accepted. Delacroix kept trying to get elected to the Institut de France (to Baudelaire’s bafflement), succeeding at the seventh attempt, while a number of the Impressionists showed – or tried to show – at the Salon. The second half of the 19th century saw active and well-publicised breakaways: the famous Salon des Refusés, established in 1863; and, from 1874 onwards, the Independent exhibitions, of which there were eight. But even so, there was a surprising amount of overlap. Renoir and Monet turned up on the Salon’s walls; and Manet, despite being one of the Refused in 1863, played a double game, continuing to submit and show pictures long after the new painters had their own outlet. That Manet’s Bar at the Folies-Bergère, which nowadays seems one of the quintessential Impressionist paintings, was first shown (along with a Manet portrait) at the Salon of 1882 comes as a genuine shock. But then Olympia had enraged the Salon-goers back in 1865.

Nor did the modernist writers who supported the modernist painters prove unfailing, either in support or in judgment. Baudelaire believed that the painter of modern life was Constantin Guys; Zola seemed to regard painters as the provisional wing of prose naturalism, preferring them not to stray into trivial or unhelpful subject matter: he dismissed Degas as ‘nothing more than a constipated artist with a talent for the pretty’. The wildest, funniest and most violent of the writer-critics was Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848-1907), who began his moral career as a degenerate and Satanist and ended up a pious Catholic. He had a day job for thirty years with the Paris Sûreté, while also holding down night jobs as an art critic and as a novelist of Zola’s naturalist school. French journalism at the time was a largely unpoliced zone, with libel laws very weak, which allowed Huysmans to express the full scale of his rage and contempt. As Anita Brookner put it, ‘his judgments on his contemporaries were not unlike the humours of an invalid, his view of the world as subjective as that of a patient in a hospital bed.’ His misanthropy gave him much less pleasure then than it does us now.

Huysmans reviewed the Salons of 1879-82 and the Independent Exhibitions of 1880-82 at considerable length. His articles, collected as L’Art moderne (1883), have never before been translated into English, probably because he is the least known of the writer-critics, and his French is often not straightforward. Robert Baldick, biographer of Huysmans (1955) and translator of his most famous novel, À Rebours, described his style as ‘one of the strangest literary idioms in existence’. Léon Bloy, a fellow writer and fellow Catholic, described it as ‘continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the wormeaten staircase of terrified Syntax’. Brendan King, who has already translated most of Huysmans’s fiction, has produced an excellent version. Rarely can it have been such fun to read translated denunciations of so many forgotten French pictures. The edition also includes scores of small black and white illustrations, which can easily be Googled into colour. Try, for example, Peder Kroyer’s Sardinerie à Concarneau, from the 1880 Salon. A young woman sits in profile: sabots on her feet, muslin cap on her head, red scarf over her shoulders, yellowing apron. She is in a large shed, surrounded by other women, and working her way through an endless pile of sardines. Her resigned expression suggests that she already sees her life stretching ahead of her in terms of gutted fish. It is a truthful and tender picture, and as a rare image of a female industrial production line it would undoubtedly have had Zola’s approval. Huysmans gives it half a line and the adjective ‘pleasing’.

In old age, Huysmans largely turned his back on what he called ‘all that literary jiggery-pokery’. He became the first president of the Académie Goncourt in 1900, but was simultaneously an oblate at the Benedictine abbey of Ligugé near Poitiers. This spiritual seclusion fulfilled half of a famous prophecy made by the (Catholic) novelist Barbey d’Aurevilly after Huysmans published À Rebours in 1884. Barbey said that the future for Huysmans lay in a choice between ‘the muzzle of a revolver’ and ‘the foot of the Cross’. Now, as an oblate, he had to have the prior’s permission to come up to Paris on literary business. One of his fellow academicians, the novelist Joseph Rosny, remembered that ‘Huysmans behaved towards the members of the Academy like an old gentleman brimming over with consideration and respect. He seemed to have grown more compassionate, and he took a brotherly interest in our work.’

Such mellowness and charity – perhaps attributable to the Church – would have come as a surprise to those who had known him in earlier times. Léon Daudet, also one of the first ten academicians, left a rather different description of Huysmans in his memoir Fantômes et Vivantes:

He was as silent and grave as a bird of the night. Slender and slightly stooped, he had a beaky nose, deep-set eyes, sparse hair, a long and sinuous mouth hidden beneath a floppy moustache; his skin was grey and he had the delicate hands of a jewellery engraver. His conversation, normally of a crepuscular nature, consisted entirely of outbursts of disgust, sickened as he was by the things and people of his time, which he cursed and execrated: everything from the decline of cooking and the rise of readymade sauces to the shape of hats. On cue he would vomit out his century, through which he ran shivering: skinless, squirming at every contact and every atmosphere he encountered, at the stupidity he was surrounded by, at both banality and feigned originality, at anticlericalism and bigotry, at architecture put up by engineers and at bien-pensant sculpture, at the Eiffel Tower and the religious imagery of the Saint-Sulpice quarter … Most critics writing about him have based their approach on his Flemish origins, and treated him as a painter of interiors, in the style of the greater and lesser painters of the North; but within him there was also a ferociously cocky Parisian, quick and colourful in his judgments, and first-rate in irritability.

Huysmans was a great hater of falsity: of models clothed from the costumier’s dressing-up box and pretending to be Joan of Arc while looking entirely contemporary; of nudes (such as those by Bouguereau) which didn’t look at all like naked women – ‘a kind of gaseous painting … not even porcelain … soft octopus flesh … like a badly inflated balloon’. (For Huysmans, only Rembrandt had ever painted truthful nudes.) He hated landscape artists ‘whose brushes move of their own accord’ and vast military pictures offering up ‘a frozen purée of combatants’. For one so sensitive and so irritable, reviewing the Salon must have been a secular martyrdom. The 1879 Salon was ‘a heap of crackbrained nonsense’: of its 3040 pictures ‘not a hundred are worth looking at’ and the other 2940 were ‘certainly inferior to the advertising posters on the walls of our streets and on the pissoirs of our boulevards’. His account of the 1882 Salon begins: ‘Once you’ve seen one Salon, you’ve seen them all.’ If the Impressionists, in their shifting composition and nomenclature, were also known as the Independents and the Intransigents, Huysmans is the most intransigeant critic of the age. At times it almost makes you feel sorry for that modestly talented, modestly ambitious young or middle-aged painter hoping that their picture wouldn’t be hung too high, that their version of landscape or history will catch the acquisitive eye of a passing visitor, that they themselves may find favour with the high chiefs of official art and – one day – win a medal and thus be exempt from the selection process for the rest of their painting life. Almost.

Huysmans loathes Salon stalwarts like Léon Bonnat (‘never has a more belaboured, more pitiful painting come off the dull trowel of that mixer of mortar who goes by the name of Bonnat’), whose influence as juror at the Salon and teacher at the Académie had deformed generations of young painters; or Gérôme, with his glossy, influential, ‘oft-repeated nonsense’; or Henri Gervex, who started promisingly but flopped back into conventionality. As Daudet pointed out, he was enraged by ‘feigned originality’ such as the ‘fake modernity’ of Jules Bastien-Lepage, a ‘prudent rebel’ who was no more than ‘a sly fellow-traveller of modernism’. Huysmans salutes a heroic military picture – a sapper pointing heaven out to a dying rifleman – as ‘the most powerful disinfectant I know for spleen, and I recommend it to anyone who has difficulty laughing’. He invents categories of badness for painters: there are the ‘couturiers’, who paint clothes rather than character, the ‘vaudevillistes’ with pretensions to wit, and the self-explanatory ‘weepies’. The fundamental failure of Salon painters was their refusal to paint what was in front of them, their sheer inability to see, for instance, that ‘the trees growing in Paris are not the same as those growing in the countryside.’ In 1879, Bastien-Lepage exhibited October: Gathering Potatoes, which features a female potato-picker, pretty, genteel and ‘lethargic’, straight out of the studio models’ listings, a suspicion of make-up on her cheeks. With grouchy pedantry, Huysmans points out that ‘the hands of his peasant aren’t the hands of a woman who delves in mud, they’re the hands of my maid, who dusts as little as possible and who barely even does the washing up.’ Contrast this with the way Degas portrays his ballet dancers. ‘Here,’ Huysmans writes, ‘there’s no smooth creamy flesh, no silky gossamer skin, but real powdered flesh, the painted flesh of the theatre and the bedchamber, just as it is, like flannelette, with its veiny granularity when seen up close, and its unhealthy sheen when seen from a distance.’

At root, truth to life in painting is truth to light. Huysmans – of Dutch origin – is extremely sensitive to its representation, and misrepresentation. And in his view French painters had long stopped looking at light as it is. Instead, they automatically imported the illumination of the old masters, with Dutch, Italian or Spanish light unthinkingly transplanted into Parisian scenes. But Dutch light, governed as it is by the proximity of the sea, of canals and rising mists, then filtered through narrow sash windows with small square panes, was ‘absolutely ridiculous in Paris, in the year of grace 1880’, where the only canals are street gutters, and the drawing rooms have ‘large casement windows and clean panes with neither bubbles nor imperfections’. In another lying stratagem, painters applied ‘standard’ daylight as taught by the Académie: manoeuvring curtains on poles until you get the same bland effect ‘whether it’s supposed to be on the ground floor, in a courtyard, or on the fifth floor of a boulevard, whether in rooms that are bare or upholstered in fabrics, lit by a candle or by stained glass’. Similarly, landscapists may go out into the countryside and sketch accurately, but then return to the studio and give their pictures the same light ‘regardless of season, whether it’s midday or five o’clock in the evening, whether the sky is clear or overcast’. Jean Béraud paints a night-time scene of an open-air ball lit by circular gaslight bowls: the problem is that ‘Béraud has never, and I mean never, even noticed the pale green of leaves when lit from below, or the harsh brilliance of skies above the fierce gleam of gaslight.’ As for Bonnat’s portrait of Victor Hugo, ‘the lighting is, as usual, mad.’

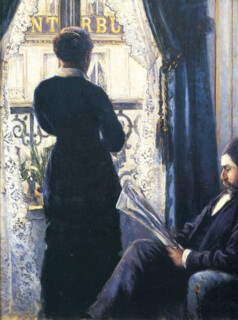

Highly entertaining though all this is, we don’t read Modern Art for its caustic denunciations – especially as few of those taunted by Huysmans have ever made much of a comeback. We read it for the speed and accuracy with which he identified and championed the new painters who in his view – and posterity’s – would supplant them. Given his central concern with light, it’s clear that Huysmans was the ideal critic to welcome the Impressionists. ‘The new school proclaimed this scientific truth: that broad daylight fades colours, that shadows and colours, of a house or a tree, for example, painted in an enclosed room, differ absolutely from the shadows and colours of a house or a tree painted under the selfsame sky in the open air.’ Of Caillebotte’s Interior, Woman at the Window he writes: ‘That supreme quality of art, life, exudes from this canvas with an intensity that is really incredible; added to which … it’s here that one should see it, the light of Paris, in an apartment located on a street, the light deadened by window hangings, filtered by thin muslin curtains.’ Of the still-lifers, Huysmans asks: ‘Where is the artist who, instead of making his objects or his flowers stand out as bright spots against a sombre background, has painted them simply, in the open air and in full daylight? … The only previous attempts to have been dared were those of M. Manet, who pulled off some paintings of flowers in real daylight.’

And as they took back control of their native French light, the new painters also took back control of subject matter. The longstanding hierarchy laid down by the Académie was now completely discarded. None of those old gods and nymphs, those ancient and Christian myths, those ‘noble’ history paintings, and so on. Flaubert had written that ‘everything in art depends on the execution: the story of a louse can be as fine as the history of Alexander the Great.’ Now, in 1880, the year of Flaubert’s death, as if in homage, Huysmans writes: ‘It’s … quite useless to choose subjects that are said to be more “elevated” than others, because subjects are nothing in themselves. Everything depends on the way they are treated.’ Even so, theory and practice don’t always accord. A couple of pages later, Huysmans is denouncing a ‘democratic and liberal still life’ of a politician’s desk as unacceptable subject matter, as a ‘monstrosity’: ‘When will we see Robespierre’s chamber pot or Marat’s bidet in the Salon? When, supposing a change of government comes about, will we see Louis-Philippe’s umbrella, Napoleon’s catheter, or Chambord’s hernia pads?’ As for Flaubert: in 1877, writing to Turgenev, he dismissed the Impressionists as ‘a bunch of jokesters, trying to delude themselves and us into believing that they have discovered the Mediterranean’.

And yet – and happily – the story is more complicated than we might have expected. It isn’t the case that everything suddenly changed for Huysmans and the avant-garde trainspotters the day Monet painted Impression, Sunrise. He didn’t write about the first four Independent shows, but it’s clear that at first the Impressionists didn’t make much of an impression on him. He saw their opening group show at Nadar’s photography studio in 1874 and then their second one at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1875. And what he found on display were ‘touching follies’ that should be examined not aesthetically but as ‘a matter of physiology and medicine’. The painters were suffering from ‘monomania’: one would see intense blue in everything, another purple, tingeing everything with lilac and aubergine. Green disappeared from their palettes, as it did for patients suffering from atrophy of the nerve fibres in the eye. ‘Ultimately, most of them would have confirmed Dr Charcot’s experiments on the deterioration of colour perception, which he’d observed in many hysterics in the Salpêtrière hospital.’ Colour theory (or at least colour thought) is reduced to a retinal disorder – as it would be by others who attacked the Impressionists in subsequent decades. Le Figaro agreed with the diagnosis of monomania. Of the 1874 show, it wrote that the new painters merely flung a few colours together and imagined the result a masterpiece ‘in the same way that lost souls in the Ville-Évrard insane asylum pick up a pebble in the road and imagine that it’s a diamond. A frightful spectacle of human vanity straying into dementia.’

What happened over the next few years, in Huysmans’s analysis, was that painters like Monet and Pissarro jumped ‘from bad to good’. Pissarro started off painting ‘vague motley-coloured canvases’, then developed into ‘a landscape artist of talent at times, but often unhinged, a man who either gets it completely wrong or else calmly paints a very beautiful work’. Monet seemed at first to be a ‘stammering’, ‘unmethodical’ and ‘hasty’ painter, his Impressionism ‘the poorly hatched egg of realism’, ‘painting left in a rudimentary and confused state’, and Huysmans lost interest in him. But then Monet’s eye was ‘cured’, whereupon he grasped ‘all the phenomena of light’, emerging, in the critic’s final judgment, as ‘a seascape artist par excellence’. Even Caillebotte, whom Huysmans came to rate straightforwardly as ‘a great painter’, started off suffering from ‘indigomania’. But ‘after being cruelly afflicted, this artist has cured himself and, apart from one or two relapses, he seems to have finally managed to clarify his eye.’ However, it’s not at all apparent how such ‘clarification’ took place: was it the result of hard work, or of a knock on the head? Which leaves us with an alternative explanation: that after several years of looking at Impressionist pictures, Huysmans managed to clarify his eye, and came to understand the revolution that had been taking place. There is also the overlapping matter of personal taste: Huysmans never came round to the fluffier, white-dabbing aspect of Impressionism.

This is clear from his attitude to the movement’s two women painters, Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. Malely, he describes the first as Manet’s pupil and the second as Degas’s – true in neither case. Morisot was one of the founder Impressionists of 1874 and Huysmans barely has an unpatronising word to say about her. The ‘unfinished’ sketches she shows at the 1880 Independent show are ‘a chic jumble of white and pink’; the following year she ‘limits herself to improvisations too summary and too constantly repeated without the slightest variation’, while being ‘one of the few painters who understand the adorable delights of the fashionable woman’s toilette’. In 1882: ‘If it were a dinner, her painting would always be the same insubstantial vanilla meringue dessert!’ Whereas Cassatt – whom he sees, oddly, as ‘a student of the English painters’ – has emerged as ‘an artist … who owes nothing to anyone, a wholly spontaneous, wholly original artist’. She paints babies – which normally give Huysmans ‘the shivers’ – with a ‘delicious tenderness’ and ‘manages to extract from Paris what none of our painters know how to express: the joyous quietude, the calm good-naturedness of an interior’.

In sum, he finds Cassatt ‘more balanced, more tranquil, more intelligent’ than Morisot, and this explains some of the basis of his taste. He is interested in light and a democracy of subject matter and a truthful eye. He is less interested in the ‘irrational’ fragmentation of colour and the fleeting impression. It’s also the case that he applauded many non-Impressionists just as loudly. He greatly admired Moreau and Redon (not only in these essays – he devoted half a chapter to them in À Rebours), as well as Fantin-Latour and Raffaëlli. Writing of Christoffel Bisschop’s The Eternal Giveth, the Eternal Taketh Away, a Dutch picture in the 1880 Salon of a grieving mother, an empty cradle and a sympathetic onlooker, he praises its un-Frenchness, its sobriety, its refusal to direct our emotions. ‘By force of good faith M. Bisschop isn’t ridiculous for a second.’ To my eye it looks pious and mock-medieval. Huysmans compares it to a Vermeer: ‘It’s a luminous painting … highly finished and very spacious.’ That ‘highly finished’ is significant. The average Salon picture was, of course, also highly finished, but highly wrongly finished.

Félix Fénéon described Huysmans as ‘the inventor of Impressionism’. ‘Endorser’ might be better (we shouldn’t allow critics too much power). But his one enduring claim to fame is that he was the first person to see Degas as the greatest painter of the age, ‘the one who has remained the boldest and the most original’. Huysmans first came across him in 1876, when he’d shown two pictures of ballet dancers:

The joy I experienced then, wholly boyish, has since increased with each exhibition in which Degas has featured … A painter of modern life has been born, and a painter who doesn’t derive from anyone, who doesn’t resemble anyone, who brings a whole new flavour to art, wholly new techniques of execution. Washerwomen in their shops, dancers at their rehearsals, café-concert singers, theatre scenes, racehorses, portraits, American cotton merchants, the paraphernalia of bedrooms and theatre boxes, all these divers subjects have been treated by this artist, who nevertheless has acquired a reputation for only painting dancers!

‘What truth! What life!’ Huysmans exclaims. This is not – or not only – the response of a sophisticated connoisseur: it is simple, ‘boyish’ awe. ‘What a study of the effect of light!’ What an ability to ‘forge neologisms of colour … and what a definitive abandonment of all the techniques of light and shade, of all the old impostures of tones’. Look at the artist’s portrait of Edmond Duranty: ‘Up close, it’s a slashing crosshatch of colours that clash against each other, that seem to overlap each other; at the distance of a few steps, all this harmonises itself and melts into the precise tone of flesh, of flesh that breathes, that lives, and that nobody in France has known how to do until now.’ Again: ‘No painter since Delacroix – whom he’s studied for a long time and who is his true master – has understood the marriage and the adultery of colours like M. Degas; no one today has a drawing style so precise and so broad, a touch for colouring so delicate … When will it be understood that this artist is the greatest we have today in France?’ ‘The marriage and the adultery of colours’ – this wonderful phrase takes us back to a scene in Maxime Du Camp’s memoirs, of Delacroix spending an evening bent over a basket filled with skeins of wool, picking them up, grouping them, placing them against one another, separating them shade by shade, and ‘producing extraordinary effects of colour’.

And then, only a year later, Degas strikes again. Huysmans had long been of the opinion that French sculpture was even more moribund than French painting, locked into old forms, old techniques and old materials. A tradition which Degas demolished with a single work in the 1881 Independent show, The Little 14-Year-Old Dancer, before which ‘a confused public has fled, as if in embarrassment’. Huysmans declared that Degas had ‘immediately made sculpture completely individual, completely modern’. A painted head, a corsage of kneaded wax, skirts of muslin, a leek-green ribbon at the neck and real hair: ‘At once refined and barbarous in her machine-made costume and her coloured flesh which palpitates, furrowed by the working of the muscles, this statuette is the only real attempt at sculpture I know of.’ And because of such profound originality, he concludes, ‘I have strong doubts that it will obtain even the slightest success.’

Huysmans isn’t the sort of critic who latches onto a new movement and applauds slavishly as a way of applauding himself. His doubts and vacillations make him the more interesting, and he is inclined to be schoolmasterly. At the Seventh Independent exhibition, Gauguin, whom he had been the first to notice favourably, is ticked off (‘No progress, alas’); Morisot likewise (‘Always the same’). He can misread paintings. At the same show, Renoir – ‘a gallant and adventurous charmer’ – offers the public the still charming and ever popular Lunch in Bougival. ‘A few of his boatmen are good, some, among his women, are charming, but the painting doesn’t smell strong enough,’ Huysmans decides. ‘His whores are chic and merry, but they don’t give off the odour of a Parisian whore; these are springtime whores freshly disembarked from London.’

Throughout Modern Art, Huysmans is unwavering in his insistence that women should look like women – that’s to say, the women they are meant to represent. Don’t just dress up a model; don’t show potato-pickers with the unblemished hands of a lazy housemaid; and above all – Huysmans is rather obsessed with this subject – show whores as they are. This is an echo of Huysmans the prose naturalist, and the unforgiving view at least displays commitment. The only problem with his disparagement of Lunch in Bougival is that the participants aren’t in fact boatmen with native – or even imported – whores: they are a group of Renoir’s friends, including Caillebotte and the poet Laforgue, entertaining some well-known actresses, including Renoir’s future wife.

By the time Huysmans saw the Salon and Independent shows of 1882 he had become bomb-happy and trench-weary. Gervex received his annual instruction to put on the dunce’s cap for painting ‘tall coalmen scrubbed clean with herbal soap’. But Huysmans was also getting grumpy with those he had previously praised. Despite having admired Sargent’s ‘soft and dreamy’ portrait of Carolus-Duran, he loathed the crowd-pleasing swagger and ‘turbulent pastiche’ of his El Jaleo, which still pleases crowds at the Frick. His staunch admiration for Fantin-Latour is now tempered: the ‘portraits are superb but will never change’. But his most surprising response is to Manet’s masterpiece Bar at the Folies-Bergère. Huysmans had already expressed the view that Manet ‘remains incomplete’ as a painter and that some of his work is ‘going downhill’; here he praises the modernity of the subject, the ‘ingenious’ placing of the bar-girl and the liveliness of the crowd. The problem is that old and essential one, the quality of the light:

What’s the meaning of that lighting? Is that supposed to be gaslight or electric light? Come off it! It’s as if it was set in the open air, it’s bathed in pale daylight! As a result, everything collapses – the Folies-Bergère only exists, and can only exist in the evening, so however knowing and sophisticated the painting is it’s absurd. It’s really deplorable to see a man of M. Manet’s quality sacrificing himself to such subterfuges and, to be blunt, making a painting as conventional as those of everyone else.

Time to retire? Time to admit, at least, that the implacable aesthetic which impelled the critic to such cheering rage against the Salon needs to be adjusted to take in all the stretchings and loosenings and formal developments of the new art. (So he doesn’t confront Manet’s unrealism in all the ‘impossible’ mirrorings behind the bar girl.) Art moves on; portrayal of light moves on; ‘finish’ moves on. But the irony here is that within two years Huysmans would himself be publishing his own great act of disobedience to Zola’s school of realism: his unruly masterpiece, his ‘wild and gloomy fantasy’, as he called it, À Rebours.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.