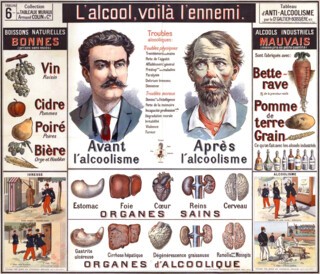

Awidely distributed temperance poster from 1902 produced by Dr Galtier-Boissière is headed ‘L’alcool, voilà l’ennemi.’ It shows two faces at the top. One is that of a spruce, healthily moustached young man in suit and tie, with a clear forehead and determined gaze. He is captioned ‘Avant l’alcoolisme’. Next to him is his scruffy, raddled cousin with vacant eyes, creased forehead and delinquent coiffure. He represents ‘Après l’alcoolisme’. Beneath them are depictions of their respective inner organs: stomach, liver, heart, kidneys and brain. The healthy organs resemble items you might see in the window of a classy boucherie; the drink-sodden ones, less so.

But this distinction is not what it appears to be, because ‘temperance’ and ‘alcohol’ – back there, back then – did not mean what they generally do. The healthy young man is certainly not a teetotaller, because next to him are pictures of the GOOD (in large caps) ‘natural drinks’ that he imbibes: wine, apple cider, pear cider and beer. His wrecked cousin, by contrast, drinks BAD ‘industrial alcohols’ made from potatoes, beetroot and grain. The consequences of each taste are illustrated in the bottom corners of the poster. ‘Natural drinks’ lead to mere ‘drunkenness’, illustrated by a cheerful soldier being banged up for the night to sleep it off; whereas ‘industrial drinks’ lead to ‘alcoholism’, more serious military indiscipline, penal servitude and even the firing squad.

For all its celebratory Exposition Universelle and the glamour of the Belle Époque (though not so named until four decades later), France in 1900 was an anxious and self-critical place. At the start of the 19th century, it had been the most populated of the Great European powers; now, it was the sparsest. The demographer Jacques Bertillon noted of France’s rivals that ‘they are all growing, all becoming more populous, and as a consequence, richer, stronger, more vital.’ The French were thought to be declining not just in quantity, but also in quality. Degeneration theory, popular across Europe, held that as modern civilisation advanced, humanity often declined. Alcoholism, brutishness and criminality resulted; also prostitution, physical deformity and imbecility. Worse, the prospect that some of these debilities were heritable meant that the nation was probably heading for long-term moral collapse.

At this time, the French ‘drank substantially more than any other people in the world’, according to Adam Zientek’s A Thirst for Wine and War. But whereas abstinence movements in Britain put the ‘total’ in teetotalism – you were dry or wet, and nothing in between – the French made a very large exception in the form of wine. According to both folklore and the medico-scientific thinking of the time, wine was in and of itself healthy, indeed nutritious; it had ‘anti-microbial’ properties and filled the drinker with useful sugars as well as putting a smile on the face and a song in the heart. One ‘reformer’ suggested that as long as men drank in moderation – no more than four litres a day – ‘wine was no more harmful, and markedly more beneficial, than bread.’ And whereas distilled alcohol came from some soulless factory, wine arose from the very soil of France (except for benighted northern and western parts where they drank beer and cider); so the map of France and the map of wine were co-extensive. Wine-drinking, in short, was not just enjoyable, but patriotic. And the argument was pushed even further. If you drank wine instead of industrial spirits, this actually prevented you from becoming an alcoholic. Armand Gautier, an eminent biochemist, proposed that wine’s hygienic properties ‘protected men from illnesses such as bronchitis, pneumonia, diarrhoea, rheumatism, frostbite, and, of course, alcoholism’.

The First World War, after its headlong opening phase, settled down into the static years of opposing trenches, with a subterranean life of mud and rats and artillery bombardments broken by occasional semi-suicidal attacks across no man’s land. One advantage of this stalemate was that it made supplies easier to deliver. A network of railways was developed, with huge logistic depots in the French hinterland, plus smaller ones near the action. Wine was a staple supply. At first it was sourced locally, but quality was often poor, and pricing exploitative; when the government took over, availability became more reliable and the product better. The quantity per soldier was also gradually increased: from a quarter of a litre at the start of the war to three-quarters by the end of it. None of which prevented soldiers away from the front line going on what was called la chasse au pinard, to which much time was devoted. There was also frequent pilfering of stock, coupled with an ingenuity of approach from the troops. For instance, wine was transported from the rear to the front lines in large metal bidons; and someone discovered that if you fired a blank cartridge into the bidon, it expanded the container’s capacity, bringing the thirsty poilus even more wine. As Zientek sums it up, ‘the delivery of the [wine] ration became the central ritual in the cult of pinard, a great secular republican sacrament in which poilus drank the protective and powerful blood of the soil, which is to say, the blood of France.’ Whether the poilus themselves saw it in quite that way is debatable.

Many principles and beliefs break down in wartime, and the key distinction between (good) wine and (evil) spirits was parked by necessity. Wine kept the men cheerful and able to put up with foul conditions; but when they went over the top with the high likelihood of being killed or dreadfully maimed, a little extra pick-me-up was called for. From the very start of the war, French soldiers had reported that the German corpses they came across not only reeked of alcohol but also of ether, proving that les Boches were ignoble and cowardly. But by mid-1915, the French army was regularly distributing eau de vie to its own troops; and, though there is no supporting evidence in the French military archives, many soldiers suspected it was often laced with ether. The troops called their eau de vie ration gnôle, a word one trench etymologist took to be a slang corruption of a Provençal word for ‘fog’. Wine was distributed twice a day, gnôle once, usually in the morning. Its alcoholic strength was about 50 per cent, and its effect dramatic. The war journal of a certain Léon Lebret contains this entry from 25 July 1915, when his unit attacked at Moiremont-sur-Marne:

Day of the offensive, we are in the attacking division’s reserve and they gave us a quart of gnôle that was half ether, and so we were all close to halfway crazy and there were some rolling on the ground and at 9h00 they gave the order to attack with the whole division and the cavalry behind us that will pursue the Germans.

As this implies, it might be a mistake to overdose your own troops at the wrong time, and soon a system was instituted at the front line. Fifteen or twenty minutes before the troops went over the top, they would line up for an officer to dole out this life-giving and death-defying potion. More than one observer was reminded of communicants queuing up at the altar rail before the priest. Refusal was rarely an option: the officer would insist on seeing the soldier drink it down – and watching the immediate result. That same month, the splendidly named Antoine Négroni took his last gulp of gnôle and raised along with his comrades the ‘savage cry’ of ‘à la baïonnette!’

Did it matter that men often went into battle as drunk as lords? Not in the larger scale of things, Zientek concludes. It might affect the accuracy of the attackers’ rifle fire, or their efficacy in hand-to-hand fighting, but this was not where battles were won:

The success of an attack had less to do with the infantry’s fighting power than with artillery preparation and the hardness of German defences. Indeed, whether men were intoxicated or not probably had little practical effect on their combat effectiveness during battle, as what they were asked to do – occupy space that the artillery had cleared and kill their demoralised enemies – had little dependence on their sober faculties and fine motor skills.

This is an unheroic truth, and of little comfort to the families of those machine-gunned in the mud. Whether it is easier, indeed preferable, to die when drunk or sober is a question none can answer, because we only enjoy the experience once.

Zientek is a professor of history with a strong sociological approach. His preface contains this forbidding statement of intent: ‘The model I propose to elaborate below [is this]: the alcohol supplied by the French army generated shared interoceptive and affective sensations that were then interpreted through culturally learned and contextually bound intoxication concepts, making for distinct and entraining emotional experience and group behaviours that tended to bolster the war effort.’ It’s tempting (if facetious) to rephrase this as: ‘French soldiers liked to get pissed with their mates, and it was good for morale.’ The book features tracts of prose as glutinous as Flanders mud. Happily, Zientek also cites many primary sources: interviews with survivors, memoirs, letters and censorship records. In 2014, Lucien Barou produced Les Mémoires de la Grande Guerre, a five-volume anthology of soldiers’ experiences, collected over forty years, which had begun as a linguistics thesis in the 1970s. Here the men speak as men do, with no theory attached to their lives. Alphonse Solnon put it this way, ‘in a very solemn and strong tone’, many years after the war was over:

I’m telling you this: without alcohol we would not have had the victory! I’m telling you this sincerely: without alcohol, we would not have seen the victory … You were a crazy man with the gnôle, you didn’t know anything. If we hadn’t had it, we wouldn’t have won the war … I’m not afraid to say it often: if we were victorious, it’s because we were full of alcohol! Because with alcohol, well, it transforms a man. Alcohol transforms a man!

Hardly the language of a recruiting poster, but a clear, truthful, rightly repetitive voice coming to us from a century away.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.