‘The Wombat ,’ Dante Gabriel Rossetti wrote in 1869, ‘is a Joy, a Triumph, a Delight, a Madness!’ Rossetti’s house at 16 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea had a large garden, which, shortly after he was widowed, he began to stock with wild animals. He acquired, among other beasts, wallabies, kangaroos, a raccoon and a zebu. He looked into the possibility of keeping an African elephant but concluded that at £400 it was unreasonably priced. He bought a toucan, which he trained to ride a llama. But, above all, he loved wombats.

He had two, one named Top after William Morris, whose nickname ‘Topsy’ came from his head of tight curls. In September 1869, Rossetti wrote in a letter that the wombat had successfully interrupted a seemingly uninterruptable monologue by John Ruskin by burrowing its nose between the critic’s waistcoat and jacket. Rossetti drew the wombats repeatedly; he sketched his mistress – William Morris’s wife, Jane – walking one on a leash. In the image, both Jane and the wombat look irate. Both wear halos.

It isn’t difficult to understand Rossetti’s devotion. Wombats are deceptive; they are swifter than they look, braver than they look, tougher than they look. Outwardly, they are sweet-faced and rotund. The earliest recorded description of the wombat came from a settler, John Price, in 1798, on a visit to New South Wales. Price wrote that it was ‘an animal about twenty inches high, with short legs and a thick body with a large head, round ears, and very small eyes; is very fat, and has much the appearance of a badger.’ The description implies only limited familiarity with badgers; in fact, a wombat looks somewhere between a capybara, a koala and a bear cub.

Despite the fact that they do not look streamlined, a wombat can run at up to 25 miles an hour, and maintain that speed for 90 seconds. The fastest recorded human footspeed was Usain Bolt’s 100m sprint in 2009, in which he hit a speed of 27.8 mph but maintained it for just 1.61 seconds, suggesting that a wombat could readily outrun him. They can also fell a grown man, and have the capacity to attack backwards, crushing a predator against the walls of their dens with the hard cartilage of their rumps. The shattered skulls of foxes have been found in wombat burrows.

Wombats are careful and protective mothers, giving birth once a year in the spring. Like all marsupials, they produce tiny embryonic young, born after only thirty days in utero, which then take refuge in the mother’s pouch for eight months and develop further. The wombat’s pouch is positioned upside down, so the joey’s head looks out between the mother’s hind legs, in order to allow her to dig without filling the pouch with mud. It’s an extraordinary bit of animal adaptation that also makes it seem as though the mother wombat is in a state of constant, eight-month labour, which explains why it was a kangaroo who got to be in Winnie the Pooh.

To early settlers in Australia, wombats were pests. Although wombat hams, like kangaroo steaks, could supplement the scant settler diet, they were primarily regarded as a potential threat to crops, and were slaughtered en masse. In Victoria in 1906, wombats were classed as vermin; in 1925, a bounty was introduced, and hunters could make ten shillings per wombat scalp. The bounty incentivised hunting; in one year, more than a thousand wombat scalps were traded in by a single landowner. Now, despite its name, the common wombat is no longer common. Overgrazing and the destruction of their natural habitat has caused a sharp drop in their numbers; all species of wombat are now protected, and the northern hairy-nosed wombat is critically endangered. It has sleeker, softer fur than the common variety, and poor eyesight, relying on its large silky nose to guide it to food in the dark. As its habitat has slowly been cut away, it has become one of the rarest land mammals in the world. A census in 1982 put the surviving number at thirty. The last census, in 2017, found that 251 wombats had evaded the clumsy destructions of humankind.

Other wombats have died more directly at human hands. In 1803, Nicolas Baudin, the famed explorer, returned from a journey to New Holland (now Australia) with an ark of animals for Napoleon’s wife, Josephine. The voyage was bleak, with a high death count among its company and cargo: more than half the crew had to abandon ship owing to illness, ten kangaroos died of exposure, and the botanist had his room dismantled to make an indoor space for the remaining animals. The sick emus were fed sugar and wine and grew sicker, and Baudin himself began spitting blood. Two wombats died, but at least one other was delivered into the arms of the Empress Josephine.

Wombats have offered solace where little other solace could be found. Theodor Adorno was a frequent visitor to Frankfurt Zoo after the Second World War. He wrote to the director in 1965: ‘Would it not be nice [or ‘beautiful’: ‘wäre es nicht schön’] if Frankfurt Zoo could acquire a pair of wombats? … From my childhood I remember great feelings of identification with these friendly rotund animals, and would be filled with delight to see them again.’

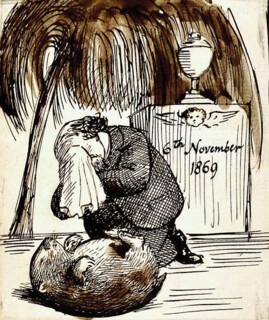

It is not always enough to be loved. Rossetti’s wombats did not thrive in captivity. His last wombat sketch is of himself, his handkerchief covering his face, weeping over the dead body of a wombat. Below he wrote a mournful quatrain, riffing on Thomas Moore:

I have never reared a young Wombat

To glad me with his pin-hole eye

But when he was most sweet and fat

And Tail-less; he was sure to die!

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.