Not long ago , a woman several years older than me and very much more successful leaned across a table to offer some assistance: ‘I can see you’re at the point where you’re feeling that you need to have a child,’ she said. ‘And I just want you to know that you can wait that feeling out. It passes.’ We’d only known each other an hour or so. Clearly my anxieties must have been leaching all over the place. She elaborated: if I thought I might have important work to do in the future, I should consider writing off reproduction and doing that instead. Whether important work meant writing something good or fighting political injustice or some other thing entirely wasn’t spelled out, but either way, a baby would be draining resources that might be better used elsewhere. Though few people say it to your face, this idea is hard to escape. If you try to care for more than one kind of thing, the op-eds imply, expect to do it badly. One of the few accounts of women’s lives in which that notion feels utterly foreign is the work of Grace Paley, where the typewriter sits on the kitchen table and single mothers do their political organising at the playground. You don’t have a story, Paley warned her writing students, if you’ve left out ‘money and blood’, i.e. how your people make their living, and whom they’ve been forced to live alongside.

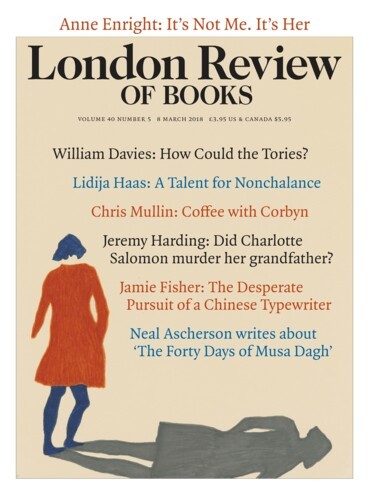

I’m aware that it’s embarrassing to begin speaking of her in this way, since Paley is known not as a purveyor of self-help but for writing some of the more ambitious and surprising American short stories of the 20th century. And while she did write about gossip, women’s friendships, long days alone with toddlers and other aspects of experience that were not, in the 1950s, generally considered the stuff of serious fiction, even some of the great men of the day were so impressed as to call her work ‘unladylike’ (in the blurbs at the front of her 1994 Collected Stories, she receives that compliment from both Edmund White and Philip Roth). Still, A Grace Paley Reader, the most recent posthumous collection of her work, in giving some of her lectures and occasional pieces equal space beside samplings of the poems and the better-known stories, celebrates Paley the person as much as the writer, and seems to invite a personal response.

Fairly comprehensive volumes of her fiction, essays and poems, respectively, have been available for some years, but this is a book precisely tailored to its moment: one in which an outspoken commitment to feminist and radical causes and regular public protest have become fashionable again, even respectable. Kevin Bowen, the book’s co-editor, writes in his introduction of his hope that the volume would ‘not only be a reminder of the power of a story well told but would also recognise the achievements of a generation of activists who stood up in the causes of civil rights, social justice, non-violence and peace, often putting their bodies on the line’. In his preface George Saunders, though he stays in his corner by focusing mostly on the fiction, suggests that reading Paley will spark ‘a revived concern for other people’s suffering’ and ends by recommending her work to anyone ‘looking for a more full-hearted way of being in the world’. I confess that my own heart rather sinks at this, as there’s no shortage of full-heartedness to be found elsewhere – and it certainly isn’t what distinguishes Paley’s stories. The short afterword by her daughter, Nora, is sharper and a bit less effusive: ‘I recognised her open water intelligence but there was always a shark swimming through it’; ‘Her dying was not like her, but she knew everyone else did it.’ Still, it confirms the impression of heroic charm created by the book as a whole. Nora recalls people in the 1960s who admired Paley’s activism but had no idea that she wrote, and vice versa – easy to understand when you read the accompanying chronology of her life, in which books and prizes take up less space than political activities. All gusto, fun and generosity, Paley emerges as a figure so appealing that she risks outshining her own fiction.

Born in 1922 to Russian Jewish parents who had left Ukraine 16 years earlier, Grace Goodside (originally Gutseit) grew up in the Bronx, hearing Russian and Yiddish and all the clamourings of New York City. Her parents were socialists and so was she, although she notes in the first essay collected here that, after her mother made nine-year-old Grace pull out of a play her youth group were doing on account of her awful singing voice, ‘in sheer spite I gave up my work for socialism for at least three years.’ She did all kinds of jobs and at 18 studied at the New School with W.H. Auden, who did her the great favour of encouraging her to write the way she talked. She married Jess Paley in 1942, in her late twenties had Nora and a son, Danny, and in her thirties began to write fiction and take part in the political activism that would continue to absorb much of her time and energy until her death in 2007. The Vietnam War, nuclear proliferation, US actions in Central America, the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and eventually the war in Iraq: she protested and organised against them all, and those fights marked her fiction. Her last collection has characters disagreeing about Golda Meir and discussing Mao. She taught writing at various universities from the mid-1960s onwards and, after separating from Jess Paley, married the writer Bob Nichols. She also published three books of fiction, though the novel her publishers hoped for never materialised. It seems fair to say that the short story was her form. The talent for nonchalance and compression that allows her to stretch out a brief chat to encompass several lives might be wasted if it extended much further. As it is, in her work possibilities proliferate rather than narrow. Paley often reuses the same narrator, but that person never needs to have learned from or remembered what seemed to define her last time round.

When Paley set out to write about women and children, she did so not as a miniaturist or a seeker of unspoiled territory but because she had a sense of the subject’s urgency. In a short piece included here on ‘The Value of Not Understanding Everything’, she neatly inverts the MFA injunction to ‘write what you know’ – the best way to end up with something dead on the page – by recommending that you go straight for what you least understand. It’s a real mistake, she suggests, to assume that what is nearest to the foundations of your own life is what you know best: nothing dulls the senses like proximity. Parents, for instance: ‘You’ve seen them so closely that they ought to be absolutely mysterious. What’s kept them together these thirty years. Or why is your father’s second wife no better than his first?’ If you find you already know the answer, she writes, ‘drop the subject.’ The vast majority of her stories seem to take place within a few New York City blocks, and even those that stay inside one or two apartments often appear via a strange accordion effect to contain whole lives and landscapes:

In many ways, he said, as I look back, I attribute the dissolution of our marriage to the fact that you never invited the Bertrams to dinner.

That’s possible, I said. But really, if you remember: first, my father was sick that Friday, then the children were born, then I had those Tuesday-night meetings, then the war began. Then we didn’t seem to know them anymore. But you’re right, I should have had them to dinner.

Paley’s domestic sphere is never cut off from the rest of the world.

In part the reason is that Paley didn’t divide those things in life either: the other mothers in the park or at the shops or on marches were her political comrades and her starting points for philosophical inquiry. ‘When I came to think as a writer,’ she said, ‘it was because I had begun to live among women.’ She was a Jewish writer in a totally different sense from someone like Philip Roth, and though she was often placed in the tradition of Isaac Babel, she told an interviewer that she hadn’t read him before she started publishing fiction and that it was a question of familial rather than literary lineage: ‘I would say we had the same grandfather. So it’s an influence that’s linguistic and social more than anything else.’ Even bringing her fiction into the world was a process she described as a more or less contingent part of social life: she had some uninterrupted time to work on the early stories when, due to an illness, someone else looked after the children for a while; her first collection came out in 1959 after another mother from the neighbourhood insisted that her ex-husband, an editor at Doubleday, have a look at them. Paley claimed in a brief tribute to Donald Barthelme, her friend and neighbour on West 11th Street, that only thanks to him had she brought out her second collection. In 1973, 14 years after the publication of The Little Disturbances of Man, he came over to say that she must by now have enough stories lying around the house to make another book; she demurred, then dug through her files, then went back to look again when he assured her she had missed out a couple. Enormous Changes at the Last Minute appeared in 1974. She rightly believed that any story had to contain at least two stories in order to work, and this one, disguised as an anecdote about Barthelme’s generosity, is also about the part fiction played in Paley’s life – it was as essential as her activism, which is to say it was part of the fabric of her day. It seems she wasn’t a careerist, or the kind of artist who sacrifices other things and people for more time alone in a room.

Her life and work visibly fed each other, and not merely in the usual sense of scavenging friends and acquaintances for material, though Paley most certainly did that, and it made for many-voiced and densely peopled fictions. Her best stories seem powered by their opening sentences, as if they have taken off from a stray remark and from there sustained themselves on a single breath. ‘I was popular in certain circles, says Aunt Rose’ is how the first story she published, ‘Goodbye and Good Luck’, begins. Though only some of these are lines she actually heard, very few seem contrived. She’s said to have put stories together bit by bit, sometimes stitching sentences and paragraphs one after the other on old bills and menus whenever she could snatch the time to write, and occasionally adding a scene to a story after its initial publication, altering its mood entirely. The most obvious example is ‘Faith in a Tree’, in which her favourite recurring protagonist, Faith Darwin, is talking to friends and children in the park. It originally ended with Faith’s erotic daydream about Philip, one of the people she’s speaking to. He blushes, and she thinks ‘as I watched the blood descend from his brains that I would like to be the one holding his balls very gently, to be exactly present so to speak when all the thumping got there’. All the men she knew, Paley told the Paris Review in 1992, were extremely keen on this ending, but the final version takes a different turn, after a bunch of Vietnam protesters come banging their pots and pans through the park, and Faith’s son is struck by their slogan (‘Would You Burn A Child? When Necessary’). In both versions it’s thought and speech that constitute the action, but the finished story is especially characteristic of Paley’s work from the 1970s onwards, allowing Faith’s social life, sexual fantasies and shifting political awareness to occupy a single space.

Asked in the same Paris Review interview whether it’s good for a writer to be politically engaged in turbulent times, Paley registered the question’s absurdity, refusing the notion that politics might be a harmful distraction for an artist: ‘It certainly isn’t antithetical to a passionate interior life – all that noise coming in. You have to make music of it somehow.’ Allan Gurganus, who studied with her as a young man, has described how, in her classes, everyone was encouraged to talk at once, with Paley acting as conductor – he remembered it as ‘stereophonic sound’. From childhood, she had been at ease amid bustle and mixing, which became for her a matter of both habit and principle. The most memorable non-fiction piece included here is ‘Six Days’ from 1994, an account of her brief time in jail at the age of 45 for, as a fellow inmate put it, ‘sitting down front of a horse’ to protest against the draft. The essay crams several life stories into just a few pages – the women in her cell tell her of their children and their drug addictions; Helen, white and Jewish, describes her estrangement from two of the other inmates, former sex-work comrades Evelyn and Rita, after the advent of black power – and in passing defends Andrea Dworkin, not for her ideas but for her courage when arrested and the practical benefit it conferred on other women who, after she stood her ground, no longer had to suffer such extreme and humiliating physical searches. It also reaches different but related social and literary conclusions: Paley takes from the women serving longer sentences a lesson about the creative value of the oral tradition and of memorising poetry and songs; and she notes how much better it was to have the women’s prison situated, as it then was, in the centre of town, where families and friends could come by and shout messages through the windows, as opposed to now, when it has long been ‘removed from Greenwich Village’s affluent throat’ and hidden where it’s less accessible to visitors, and the rest of the citizenry can comfortably forget all about it. Essays like this one offer a fascinating record of the time, though they’re simpler, less finely wrought than the fiction, in which Paley is often more subtle and fleet-footed in her treatment of politics.

Since her stories are structured by the rhythms of thought and conversation – the characters’ or the narrator’s – they can travel anywhere swiftly and smoothly without seeming fragmentary or surreal. The effect can be especially striking in her shortest stories: ‘Wants’, in which a woman at long last returns two Edith Wharton books to the library and pays her $32 fine, evokes a full span of debts and disappointments, hopes and habits, and the unaccountable passage of the years in not much more than two pages. It begins: ‘I saw my ex-husband in the street. I was sitting on the steps of the new library. Hello, my life, I said.’ As so often in Paley’s stories, small elements of what could be called metafiction – as characters consider their own experiences as if they were fiction – deepen the reader’s sense of an emotional reality: ‘I wanted to have been married for ever to one person, my ex-husband or my present one. Either has enough character for a whole life, which as it turns out is really not such a long time. You couldn’t exhaust either man’s qualities or get under the rock of his reasons in one short life.’

Life is lived in the same way as stories are written. Paley sometimes calls it ‘thickening’, this self-fictionalising impulse in even the most basic operations of memory and imagination, the way ‘the lifelong past is invented, which, as we know, thickens the present’. What Paley does on the page is presented as a more intense form of what’s done all the time. Her characters speak the way real people do but also as they would if they could speak a heightened essence of themselves – the two modes binding together as the story evolves. Dotty Wasserman of ‘The Contest’ resurfaces here and there; in later stories such as ‘Love’, she is a fictional creature suddenly remembered as a real woman by other fictional characters. This works particularly well in ‘Love’, which is in part about a happy marriage and so maps the places where people’s projections and their actual lives overlap. Near the end of it the narrator, at the grocer’s, catches sight of Margaret, a woman she hasn’t spoken to in two years after an ideological split, and who has taken with her the narrator’s once dear friend Louise. ‘In a hazy litter of love and leafy green vegetables I saw Margaret’s good face.’ Without thinking, she smiles at Margaret and Margaret smiles back – an awkward, fragile conjuring of something that had seemed permanently lost the moment before. There’s an illusory reconciliation, or perhaps it’s the rift that’s been rendered illusory all of a sudden. Either way, you’re reminded of how real and how invented most love and friendship is.

The idea that art should be sharply divided from everyday life and responsibility seems a childish oddity in Paley’s fiction, even though her women are frequently overworked and under strain, trapped at least temporarily by circumstance. In ‘Lavinia’ an ageing mother watches her daughter grow ‘busy and broad’ caring for her own children and fears she’ll never get to do anything else. Yet fundamentally Paley seems not to have believed in the sort of scarcity of time or energy, or perhaps in the illusion of autonomy, that a question such as ‘writing or children?’ requires. It implies the kind of worldview she gently makes fun of in the story ‘Listening’, when two men are overheard discussing important matters. One of them explains that he’s had to tell his current woman, Rosemarie, that he won’t have a child with her, because his son by a previous love is only 12:

I already have one child. I cannot commit suicide until he is at least twenty or twenty-two … if things do not work out, if life does not show some meaning, MEANING by God, if I cannot give up drinking, if I become a terrible drunk and know I have to give it up but cannot and then need to commit suicide, I think I’d be able to hold out eight or nine years, but if I had another child I would then have to last twenty years. I cannot. I will not put myself in that position.

The other man concurs: ‘I too want the opportunity, the freedom to commit suicide when I want to’ and notes that he has his ‘real work’ to finish in the meantime. Then ‘the men congratulated each other on their unsentimentality, their levelheadedness.’ A free and separate self is a claustrophobic fantasy. These men have something in common with Faith’s father in ‘Dreamer in a Dead Language’, who tells her he’s an idealist, which reminds her of her ex-husband:

Why did Ricardo get out? It’s clear: an idealist. For him somewhere, something perfect existed. So I say, That’s right. Me too. Me too. Somewhere for me perfection is flowering. Which of my three lovers do you think I ought to settle for, a high-class idealist like me. I don’t know.

There are plenty of jokes at various men’s expense in the stories and yet for the most part Paley likes men in the quizzical way she likes nearly everybody else – they amuse her without arousing her contempt. (‘Listening’, in fact, ends on the question of whether they’ve been liked too much, got too much attention: the avidly heterosexual Faith is unable to defend herself against her friend Cassie’s accusation that her own ‘woman-loving life’ may as well not exist for all the mention it receives in Faith’s stories.) Hers is a sturdy humanistic intelligence that ought to feel old-fashioned but is instead encouraging. Since each story is a conversation, or more than one, we always see people’s weaknesses and convictions through someone else’s eyes, aware of the things being missed, expectations surpassed, old misunderstandings skipped over or still rankling. Husbands and exes turn up all over the place, sometimes even two by two, offering the women other angles on what happened or what could have happened. Different perspectives are held in balance; no one gets to be firmly in the right for too long. The fortysomething narrator of ‘The Long-Distance Runner’, whose city jog slants sideways into a long imagined encounter with the black family now living in her old apartment, discusses men with the mother, Mrs Luddy. ‘First they make something, then they murder it. Then they write a book about how interesting it is.’ ‘“You got something there,” she said. Sometimes she said: “Girl, you don’t know nothing.”’ In ‘Zagrowsky Tells’ we see Faith from the perspective of an old man, her former pharmacist, whose racism and sexism have alarmed her. She’s suspicious, seeing him with a mixed-race grandson; he reminds her that he once took care of her feverish child and how she and her activist friends repaid him by protesting outside his shop, making him a spectacle in the neighbourhood and causing him trouble that’s still echoing into the present. No Paley story stays still long enough to become didactic or cloying.

The stories operate by a principle of exchange and interaction, where what happens and changes does so always in the unpredictable space between people. Hence the case Paley’s narrator makes in ‘A Conversation with My Father’ for the right of ‘everyone, real or invented’, to ‘the open destiny of life’. Very rarely does she subject anyone to a harsh and irrevocable fate. (‘The Little Girl’ is uncharacteristic in its violence – a horrific beating, a rape, a death.) Paley’s people reappear from story to story and their lives usually extend beyond the frame. Her suspicion of ‘the absolute line between two points’ may explain why she was so frequently accused of wisdom. If you were looking for lessons on better living, you might find them in the fiction; especially if you choose to read the fiction through the life and vice versa, as the Reader seems to encourage. ‘I learned from her,’ Nora Paley says of her mother, ‘that precision requires a warm eye, not a cold one.’ But most of the time she didn’t make things too cosy for her characters, only left the door ajar for some other thing to happen next.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.