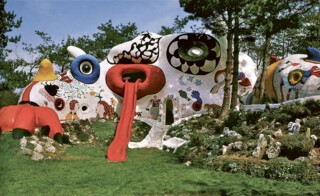

Halfway through Structures for Life, the Niki de Saint Phalle exhibition at MoMA PS1 (until 6 September), is a letter Saint Phalle wrote to her muse and sometime lover, Clarice Rivers. It’s scrawled on a 1966 poster for her walk-in sculpture, Hon – en katedral (‘She – a cathedral’), then under construction in Stockholm’s Moderna Museet. Hon, a pregnant, reclining woman 82 feet long, was built in collaboration with the sculptors Jean Tinguely (later Saint Phalle’s second husband) and Per Olof Ultvedt. The figure housed a planetarium, a picture gallery, a snack bar, an aquarium, a cinema showing an early Greta Garbo film and a roof terrace on its massive belly. Saint Phalle’s notes to Rivers, whose pregnant body inspired the monumental Nana sculptures for which she is now most famous, record the difficulties of making Hon:

We have about three hundred cuts from the wire, five hundred bruises, burns, glue all over our hair … She is driving me insane I am completely obsessed. I can’t sleep at night … When she is finished I’ll go inside with a machine gun and kill anyone who tries to come in. I just can’t bear the idea of all those fucking people walking around inside her.

Hon’s entrance, through which seventy thousand visitors passed during its three-month existence, is annotated ‘long live the CUNT’ and then below, for good measure: ‘THE BIGEST [sic] AND BEST CUNT IN THE WORLD.’

You can tell a lot about Saint Phalle from this bit of paper: the energy and resourcefulness; the absence of any boundary between her life and work; her fondness for monstrous and mythical figures, for bold lines and curves and flat, bright colours; the subversion of women as mothers or sex objects; Warholian self-promotion and self-mythologising; the refusal of perspective (in both senses). And also a quality that runs through all her work which you might call childlike – playful, restless, silly, flamboyant, uninhibited, perverse, joyously aggressive. As Saint Phalle’s first architectural experiment, Hon is an obvious prototype for the large-scale playhouses, grottoes and sculpture gardens that Structures for Life puts at the heart of her work. So it’s surprising that the exhibition, her first major retrospective in the US, feels muted, almost dutiful – paying its respects to work whose weird, disarming power you don’t get to experience first hand. (I recently caught the last day of a smaller but more rewarding Saint Phalle exhibition at Salon 94 in uptown Manhattan. Everything from the mosaiced lions guarding the entrance to the dancing Nanas upstairs confirmed her gift for inventing things you want to grab, or climb on, that make you laugh out loud, that snag in the memory.)

This stiffness may be a result of the curators’ desire to showcase her less well-known but more ambitious projects over the beloved Nanas, and to dispel the impression of an artist too upbeat, too accessible, too feminine to be taken seriously. But it was never sunniness or girliness that made Saint Phalle so compelling. Her work conveys a curiosity about violent impulses, including her own, and a willingness to play with them. Even the Nanas carry a sense of threat, without which they wouldn’t inspire the same emancipatory glee. In her memoirs, Saint Phalle describes her childhood as the stuff of fairy tales, complete with sudden turns of fortune and monstrous acts. She was born Catherine Marie-Agnès de Saint Phalle in 1930 to a family descended from medieval French nobility. The Wall Street crash had bankrupted her father a year earlier and she lived at first in her grandparents’ château, before moving to America aged three. Her mother used to hit the children in the face with the bristly end of a hairbrush; her father, whose anti-racist and democratic values made a deep impression on her, raped her repeatedly when she was eleven – or as he later put it in a letter, ‘tried to make you my mistress’ – a betrayal that, as she wrote many years afterward in Mon Secret, exposed the whole social order around her as hypocritical and false. In the aftermath of these attacks she developed facial tics, proclaimed her atheism to the nuns at her convent school, and while at Brearley, a Manhattan private school, painted red fig leaves over the genitals of ancient Greek statues: ‘my first artistic act’. (The school insisted she see a psychiatrist or leave.)

At eighteen, she eloped with Harry Mathews, later known as the only American writer in Oulipo, and they played a bohemian version of house: seeing two or three movies a day, eating crummy Chinese food, reading in bed and singing Edith Piaf in the shower together. They moved to Europe, immersed themselves in art, shoplifted food and books – one story has Saint Phalle producing a first edition of Madame Bovary from under her mother’s mink coat. She modelled for magazine covers and considered acting (though she eventually turned down Robert Bresson’s offer of a lead role). But she’d begun hoarding knives and razor blades under the mattress and in her handbag. ‘My psychic pain was like a giant rat trap,’ she wrote later, ‘an inner scream that would not stop.’ Two years after giving birth to her daughter, Laura, she entered a psychiatric clinic in Nice, where she began to paint. In 1960, she separated from Mathews and – ‘something unpardonable, the very worst thing a woman could do’ – left their two children, aged nine and five, with him. From then on, it seems, she worked furiously, despite her precarious health. She first gained recognition for a series of shooting paintings, Tirs, in which she fired a .22 rifle at plaster surfaces containing pockets of paint, which emptied in splatters. (She also made do-it-yourself versions.) Had she been ugly, she noted, this performance may not have interested anyone; as a beautiful woman in a white jumpsuit, she was a sensation, and was even satirised in a Paul Newman movie. She made blasphemous altars covered in weapons, vermin, crucifixes (the MoMA show includes the large bronze Altar O.A.S., which attacks the Catholic Church for its role in French colonialism).

The same preoccupations recur throughout Saint Phalle’s paintings and drawings and Boschian assemblages, her sculptures, costume and set designs, TV animations and feature films (particularly intriguing is Daddy, the ‘collective and semi- autobiographical psychodrama’ of gender roles, incest and revenge she made with Peter Whitehead, which was slated by critics). She also produced consumer items such as furniture, scarves, inflatable toy Nanas – ‘my dream is for things to be in the street, for everyone, so kids can play with them’ – and jewellery and perfume in ornamental bottles, which she used to fund her other work.

A single striped Nana, Clarice Again (1966-67), dominates the first room of the exhibition: her huge buttocks, each emblazoned with the kind of flower a child might draw, are balanced by breasts that protrude so high they almost obscure her tiny head. But the room is otherwise dedicated to Saint Phalle’s outdoor follies, including her Golem in Jerusalem and Le Dragon de Knokke in Belgium; the installations she and Tinguely put together for the Stravinsky Fountain and for Expo 67 in Montreal; and her biggest public project, the fourteen-acre Tarot Garden in Tuscany, more than twenty years in the making and finally opened to the public in 1998 (Saint Phalle, who died in 2002, lived for a time in one of its larger sculptures, The Empress). These works are represented by drawings, photographs and footage of the construction process and of the results in situ, as well as other documents (‘Qui a autorisé cette horreur?’ a local newspaper asks in reference to Le Rêve de l’oiseau, a set of decorative pavilions she built in the South of France; the answer is that building carried on for three years without a permit). There are also little multicoloured clay maquettes of many of the figures which, given Saint Phalle’s taste for hearts and flowers and without the shocks of scale and context, can veer into whimsy. The videos and photographs often better serve the purpose, allowing you to imagine their full effect for yourself.

The show goes on to sample different phases of Saint Phalle’s fifty-year career. As the title suggests, special emphasis has been given to work with a communal, utopian or humanistic bent, such as Aids: You Can’t Catch It Holding Hands, a book for adolescents that she illustrated and wrote with an immunologist friend in 1987. It was translated into several languages and later distributed in French schools. This approach allows the curators to focus on the accomplishments that mattered most to Saint Phalle and took up much of her time, energy and money. It’s also true that, as one of the catalogue essays notes, Saint Phalle took unusual care to honour her many collaborators, assistants and labourers, going so far as to embed their names and casts of their hands in mosaics as part of the Tarot Garden. (It would anyhow have made sense for a woman making this work at that time to play nice.) What bothers me about the insistently public-spirited take on Saint Phalle is that it runs the risk of privileging minor pieces over what is singular and strongest in her work. I was puzzled by the prominent display of hand-drawn posters drawing attention to social issues, including one that justifies abortion rights on the grounds of overpopulation and hunger. While Saint Phalle clearly meant well, her political analysis isn’t the basis on which we should judge her. She did make connections between broader political problems (and fantasies) and private emotional ones, but she often did so most effectively by mining her own psyche. She was always inclined to position herself, in her work and in public, as the heroine of an epic, a dragon slayer who might play the dragon herself now and then. (Her granddaughter Bloum Cardenas described her as ‘a sacred monster’, who ‘burned up most of her relationships, voluntarily or otherwise.’) She also loved to provoke, and even the projects for children encourage them to explore potentially risky freedoms.

Saint Phalle’s books, many of which she drew and wrote by hand, have a sharp, sly simplicity, and unlike some of her larger works they lose nothing in a museum setting. My Love (1971) follows the course of a long love affair through lists of scattered questions, answers and confessions, stripped of some of the pretences with which adults usually protect themselves. They are spare and abject enough to conjure universal anxieties, hurts and humiliations. Their wobbly lettering and flights of fancy lend them an uneasy atmosphere of childhood, linking early, formative experiences of attachment to later disappointments. ‘You are my sun. you are my Tyrannosaurus Rex,’ she writes. ‘Where shall we make love? in a bathtub? under the stars? in the jungle with lions and crocodiles?’ (There’s a doodle for each option.) After a breakup comes a small, painful litany: ‘We won’t take any more baths together … We won’t take that trip we planned … We won’t kiss each other anymore … We won’t hold hands anymore … We won’t live in a house together.’ This should be tacky, sentimental, but it’s this movement between undignified enjoyments and sufferings that allows her to remind you of the wounds that don’t heal, the needs that aren’t met, the time that passes in a straight line while you keep circling on the same track. Her most powerful works are an expression of the mind’s dark comedy; they can’t easily be conscripted into a blueprint for better living.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.