Among the Russian novelists, poets, composers, actors and thinkers on display in last year’s compact but intense loan show from the Tretyakov Gallery to the National Portrait Gallery, Russia and the Arts: The Age of Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, were two pictures of famous collectors. The first was of Pavel Tretyakov himself, painted in 1901 by Ilya Repin, showing its tall, willowy subject, arms crossed, in shy, aesthetic half-profile; behind him are some of his holdings of 19th-century Russian art, including an edge-slice of the massive, heroic and rather ridiculous Bogatyrs (beefy medieval warriors) by Viktor Vasnetsov. The second, painted only nine years later by Valentin Serov, was cleverly positioned to be the last picture the visitor saw. It showed Ivan Morozov, one of the two great Moscow-based patron-collectors in the decades leading up to the First World War. A burly and forceful presence, Morozov gazes straight out at us, as if assessing our taste (and pocket). He is soberly dressed in black and white; behind him, in a riot of rich orange, red and blue, is one of his prizes: Matisse’s Fruit and Bronze, acquired that very year for five thousand francs direct from the painter’s studio. Rarely can a sudden change of gear – both aesthetic and acquisitive – have been so clearly marked.

Morozov was ‘the calmest of collectors’, a curator at Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts told me recently; he ‘never broke the rules’; and he tended to want paintings from throughout an artist’s career. His great rival, Sergei Shchukin, ‘was always breaking the rules’ (e.g. cutting out the dealer); he was more dramatic in his taste; and he wanted the ‘top, top’ of each painter he was interested in. Both collectors ran family textile firms (the Shchukins were merchants, the Morozovs manufacturers) and each had older brothers who had started buying art first. Ivan Morozov only began collecting on the death of his wilder brother Mikhail, who was the first Russian to buy Manet and Van Gogh – as well as the only Munch currently in a Russian public museum. Shchukin had two art-hungry brothers: Dmitri, who bought Old Masters and was the only Russian ever to have owned a Vermeer (Allegory of Faith, which he sold within a year because of doubts about its attribution) and the dandyish, Paris-based Piotr. The latter had been buying Pissarro, Sisley, Monet, Degas and Renoir for some years when he got into typical Parisian trouble: blackmailed by a (female, French) ‘companion’ with the apt name of Mme Bourgeois. Durand-Ruel, the dealer Piotr had bought his paintings from, meanly offered the exact sum he had initially paid for them; his brother Sergei generously quadrupled it, but took Piotr’s collection in exchange. Sergei, the third of six brothers, was a quiet, stammering mother’s boy with a ‘skirt education’, a lifelong vegetarian but an inner carnivore. He made a speculative fortune out of the 1905 Revolution; he took over sole control of the family business when his father died; at thirty, he married a beautiful 19-year-old Donbass coal heiress whose parents had intended her for the luckless Piotr. Such predatoriness might be put down to nominative determinism: ‘Shchukin’, I was informed, is close to shchouka, Russian for ‘pike’.

Both Morozov and Shchukin bought Impressionists and post-Impressionists; they were equally avid for Monet and Cézanne and Van Gogh and Gauguin and Matisse. Shchukin had eight Cézannes, Morozov 18; Shchukin had 16 Gauguins, Morozov 11; Shchukin had 42 Matisses, Morozov 11. Comradely rivals, they would often visit exhibitions and studios together. Morozov (the calmer one) went strongly for Vuillard and Bonnard – indeed, he commissioned for his Moscow house the biggest decorative paintings Bonnard ever produced. Shchukin bought a single Vuillard and no Bonnards at all. Morozov also bought Russian pictures, which formed more than half of his collection, whereas Shchukin was more single-minded: apart from some African and Oriental pieces, his corpus of 275 works consisted entirely of contemporary Western European art. Nor did Morozov go as far into modernism as Shchukin: he bought three Picassos as against Shchukin’s 51. Shchukin also went big on Douanier Rousseau. Both bought the Fauves; both liked early Renoir, but not the fleshier, flashier period.

These paintings – some of the least political ever painted – have had a politicised life for the last century. In 1918 Lenin signed a decree nationalising the two collections, ‘having regard for their usefulness in educating the people’. Thereafter the works formed the basis of Moscow’s State Museum of Modern Western Art (which continued to acquire pictures, some the gift of leftist painters like Léger). The museum was shut down in 1939, and in 1948 Stalin signed a decree abolishing it. Far from being useful in educating the people, its contents were now seen as being of ‘minimal ideological value, elitist, formalist … and devoid of any progressive civilising worth’. The pictures were split between Moscow and Leningrad – rather to the chagrin of Moscow, since St Petersburg had always been reactionary and inward-looking in its collecting habits. In the mid-1960s, cultural diplomacy instigated by André Malraux, then the French minister of culture, brought some of the pictures back to Paris and Bordeaux. Now the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is showing The Shchukin Collection: Icons of Modern Art until 20 February. This ‘top, top’ selection of his pictures was also intended to help normalise relations with Russia: the catalogue opens with warm expressions of Franco-Russian harmony from Presidents Hollande and Putin. These now read rather hollow: last October, Putin strangely took offence at Hollande’s suggestion that he might be indicted for war crimes, and cancelled his trip to Paris (he was also going to open a Russian cultural centre and visit the blingy gold-domed Russian cathedral which has suddenly sprouted next to the Pont de l’Alma).

Still, for a few more wintry weeks we have the pictures – and what pictures. The Russian novelist Ilya Ehrenburg reported this tribute from Matisse:

Shchukin started buying my work in 1906, at a time when few people in France knew who I was. They say there are artists whose eye is infallible. This was the case with Shchukin, even though he was a merchant rather than an artist. He always chose the best. Sometimes, when I didn’t want to lose a picture, I would say, ‘Oh, that one, it’s a bit of a failure, I’ll show you something else.’ He would carry on looking and eventually say, ‘No, I’ll take the one that’s a bit of a failure.’

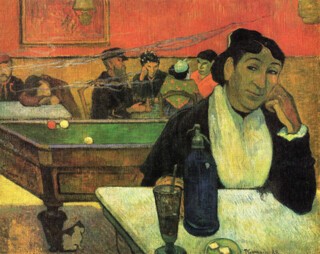

On every floor of the gallery’s new Frank Gehry building there are paintings you could spend half a day in front of, like Monet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe of 1866 (three years after the Manet of the same name), which sets the fall and sweep and swoop of human forms and clothing against the fall and sweep and swoop of nature, the two intersecting wittily in an arrowed heart with the letter ‘P’ carved into a tree trunk; or Picasso’s monstrous, brooding Trois Femmes (1908), the culmination of his ‘African’ period, which Shchukin, after a long coveting, bought from Gertrude and Leo Stein; or the saturated colours of Matisse’s La Desserte of 1908, which rules over a huge, light-filled gallery of great Matisses (how strange and amazing that Russia was the first country to which Matisse was exported). At times, you can’t decide which picture to give the next minutes of your life; at times, you are almost relieved when faced with a merely moderate Monet. But then you are sideswiped by, say, Picasso’s small, quiet collage Composition with Sliced Pear (1913), the last Picasso Shchukin bought (small is often more convincing with Picasso); or Douanier Rousseau’s double portrait of Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin, comic and touching in its monumentality; or Gauguin’s wonderfully floppy, down-at-heel Sunflowers of 1901, which can’t help but read as a reference to Van Gogh – and which also suggests that, though Gauguin’s work is often viewed as a rich account of tropical pleasure, there is always something tamped-down, even depressed, about its expression. He tells you it’s joy, or sex, or jealousy, but it looks strangely like inertia or heatstroke.

What must it have been like, you find yourself wondering, to have been that collector, with that money, in that Paris, at that time – that short, brilliant period of European art? And then to take such treasures back to Moscow, and risk them there? Shchukin hung his pictures hugger-mugger, edge to edge, in double tiers, right up to the plaster cornice, lit (it seems) only by a central chandelier; beneath them stood distinctly non-modernist furniture – gilded Louis Seize chairs and sleek silk sofas. Some friends laughed at his Gauguins, while another visitor to his Moscow mansion took what the catalogue describes as ‘un crayon protestatoire’ to one of the Monets. Now, the Parisian worshippers walk round, iPhone in hand, snapping the returning icons. It’s often easy to feel superior to the superior gallery-going French; and I did overhear an occasional, ritually disparaging murmur of ‘Oui, ce n’est pas mal’ in front of one of Shchukin’s treasures. But most visitors had a frenetic bemusedness: how can we possibly take all of this in? And the mind does keep spinning off onto other matters, like: why is that masterly Cézanne of Mont Sainte-Victoire covered with such a high-lacquer gloss finish that it spits light back at you? And don’t the Matisses look so much better in their quiet, sober frames than the gilded blaze of quadrants around the Impressionists? And, by the way, how come this show ended up at a private rather than a public institution? How much did that cost?

Then the mind settles back to the pictures, to what is there and what isn’t. First, the two elephants which aren’t in the room, but which many, including myself, somehow assumed were bound to be there. They are, of course, Matisse’s La Danse and La Musique, the twin decorations Shchukin commissioned for his Moscow staircase in 1909. When, many years later, the painter’s art-dealing son Pierre was asked if his father could have painted such enormous canvases without Shchukin, he replied, ‘Why? For whom?’ (Are they now too fragile to travel?) The next surprising absence is what Shchukin didn’t buy. Acquiring his Picassos between 1909 and 1914 (some direct from the artist’s studio), he lucked in to the high noon of analytical Cubism. He bought wonderful paintings from this period (Bouteille de Pernod et verre and Violon, both from 1912, for instance), but clearly shied away from the more abstract and the more unreadable; also from those which stripped colour right back to minimal greys and browns. Shchukin’s Picassos always have colour and readability. He stayed away from theory, just as, out of a certain pudeur (or respect for Moscow’s values), he generally stayed away from nudes and the erotic. After La Musique arrived in Moscow, Shchukin had a red blob of paint added to hide the flautist’s genitalia. When Matisse subsequently came to visit there was much anxiety as artist and collector approached the famous staircase, but the guest diplomatically observed that the obfuscation made no difference.

And here is another absence. After being shown the Pushkin Museum’s holdings of modern Western art – Morozov’s, Shchukin’s (temporarily depleted), plus some masterpieces liberated by the Red Army – I said to the curator, ‘But there’s one big thing missing.’ ‘What’s that?’ he asked. ‘Braque.’ He winced. ‘When Kahnweiler tried to get Shchukin to buy a Braque, Shchukin said, “He only paints copies.”’ I winced in return. The more so because the single Braque he did buy – Le Château de La Roche-Guyon of 1909 – is magnificent: a central core of buff-and-grey cubes, cones and rhombuses surrounded by a swirl of indistinct greenery, apart from a gesture of leaves in the top left-hand corner, like a gigantic verdant ear of corn. At the Vuitton it is placed between two Picassos: the 1908 Maisonette dans un jardin and the 1909 L’Usine à Horta de Ebro. Art is not a competition (except when it is), but the Braque quietly gives the other two pictures a lesson in harmony (not that they were aiming at harmony themselves, but still). As for copying, when Braque and Picasso joined up to take Cubism to its heights, ‘like climbers roped together’ as Braque put it, they learned – or copied – from each other; indeed, Picasso stole more from Braque than the other way round. How could Shchukin not see some, at least, of this? To make matters more insulting to Braque, he bought twice as many pictures (even if that only adds up to two) by Othon Friesz, Braque’s companion-in-brushes before Picasso. The undervaluing of Braque clearly began even earlier than I had imagined. Still, let’s look again at Shchukin’s statistics at the lower end: no Bonnards, one Vuillard, one Braque, one Burne-Jones tapestry, one James Paterson, one Auguste Herbin, two Frank Brangwyns, two Charles Guerins. That makes me feel better. It would be unbearable if, with all that money, a collector had entirely faultless taste. Though he did admit that the Burne-Jones was ‘a youthful folly’ – the adjective here meaning ‘youthful as a collector’, since he was 48 at the time.

The diminution of Braque is magnified by the promotion of Derain. Shchukin bought no fewer than 16 Derains, making him (with Gauguin) numerically the third-equal painter in the collection. Of course there are matters of availability and price; but also of personal taste and fashionability. Was it Derain’s Cubism-lite, and his easy stylistic metamorphism, that made him look more significant than he turned out to be? Shchukin bought other painters whose reputations have shifted, some up, some down: nine pictures by Marquet, four by Carrière, three by Marie Laurencin (from her best period), four by Maurice Denis (who doubtless looked the most avant-garde of the Nabis, and is now on his way back up), three by Forain, and two by Puvis de Chavannes (has anyone’s reputation fallen further in the last hundred years?). There are also two by Signac and one by Cross – which points to another intriguing absence: that of their master, Seurat. Perhaps none of his work was on the market? Shchukin also chose to have himself painted twice, both times by the same artist, the Norwegian Xan Krohn. The portraits have an angular emptiness worthy of Bernard Buffet.

This spectacular exhibition makes you think more widely about the world of art, about reputation, about the hazard of posterity, about money, about ownership, about visibility, about political interference. I went round the show with a friend who stopped in the middle of the Matisse room and said, wonderingly, ‘Perhaps there’s something to be said for the Russian Revolution after all?’ Yes, except that the revolution locked all these pictures away for decades; and that, in any case, Shchukin was always planning to leave his collection to the nation, as was Morozov. The afterlife of their pictures has been full of splittings and comings-together, both in ownership and location. In late 1888, within a few days of one another, Van Gogh and Gauguin, in Arles together, painted their respective versions of the same scene: Le Café de nuit. Soon after, the painters split (in both senses), and their two pictures went off in different commercial directions. But Morozov tracked them down and wonderfully reunited them, side by side, on a wall of his Moscow house. In 1918 they fell into state ownership, and continued, spiritually, side by side, in the Moscow Museum of Western Art. But then, in 1933, the Van Gogh was sold off for hard currency, and now hangs in the Yale University Art Gallery; while the Gauguin is at the Pushkin. No doubt some future exhibition will temporarily reunite them. As for that Serov portrait of Morozov on show in London last year, it hints at a different sort of coming-together. His background Matisse, Fruit and Bronze, was in fact a variation on an earlier picture. Morozov saw the first version, wanted it, but discovered it had already been sold – to Sergei Shchukin. He begged the painter for a variation, and Matisse obliged. The two pictures currently hang next to each other in the Pushkin Museum.

A collector is, in the end, a person who exchanges money for art, trusting either his own eye or the eye of an adviser. But the relationship between artist and patron, however harmonious on the surface, and however true the collector’s expressed admiration, is always going to be unstable. The collector may or may not have the best eye, but he certainly has the best money. He then becomes a person who owns and displays the artist’s work, and perhaps donates it to the nation – or has it confiscated by the nation. At which point he becomes an ex-collector, an ex-pike. What happens then? Shchukin left Moscow in 1918, travelling via the Ukraine and Germany to France; 18 years of exile in Nice and Paris ended in Montmartre Cemetery. He wasn’t penniless: in the 1920s he is known to have bought seven Le Fauconniers for his Paris apartment, a Dufy or two and a few Surrealists. But it seems that an ex-collector, or a collector with an eye and an instinct but now considerably less money, is not such an interesting person as before. He may have his old pride, but he also has his new shame. In Paris, Picasso – who shortly after meeting Shchukin had drawn an ugly caricature of him with a pig’s snout and ears – now complained that the collector owed him money; in Nice, there was an awkward encounter with Matisse. As Marina Loshak, director of the Pushkin Museum, put it in the newspaper supplement Russia beyond the Headlines: ‘We don’t know what would have become of Matisse if at a certain moment in his life Shchukin had not stood beside him. And it is sad to say, but when Shchukin emigrated to Paris after the revolution, none of the artists gave him the due human and moral support, including Matisse.’ This is indeed sad, though it is always useful to be reminded that artists, for all the beauty they create, can be just as pike-like as those who buy that beauty.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.