‘He has created more than any artist after Picasso,’ Jasper Johns said of Robert Rauschenberg, his one-time partner, and the Rauschenberg retrospective now at Tate Modern (until 2 April) fully attests to the sheer abundance of his six-decade career (he died in 2008). There are impressive inventions here, such as his extravagant combinations of painting, collage and sculpture, as well as mixed experiments, such as his rambunctious forays into new media technologies, but there is a lot of recycling and wheel-spinning too. No review can take it all in, so I will focus on one early phase, a key moment when, after a brief sojourn in Rome and North Africa with Cy Twombly, another close friend, Rauschenberg returned to New York in spring 1953 and set up a studio on Fulton Street in Lower Manhattan.

Before his tour abroad Rauschenberg had attended Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where, with teachers such as the former Bauhaus master Josef Albers, he absorbed as many avant-garde experiments as he could. By contrast Fulton Street was a period of reduction and redirection. It was then that Rauschenberg elaborated his materialist reinterpretations of the monochrome, known as the White and Black Paintings, as well as his rudimentary arrangements of found rock, scrap metal and old twine, known as the Elemental Sculptures. What motivated such austere works? What prompted his interest not only in material process but also in conceptual gestures? It was during this time, too, that Rauschenberg asked Willem de Kooning, whom he greatly admired, for a drawing, which he then laboriously erased. This is a bizarre collaboration, but a collaboration nonetheless, and this distinctive aspect of his artistic practice was also developed on Fulton Street.

Although the White and Black Paintings qualify as monochromes, in other respects they are opposed. Applied with rollers on panels, the Whites have little inflection, and Rauschenberg said they could be repainted, even remade (as some were in 1965 and 1968), while the Blacks have almost too much texture: built up of newspaper strips dipped in paint, glued to canvas, then coated with more paint, they appear worn and fragile, and some show a range of colour and tone too. The Whites appear pristine, empty, flat and serial; the Blacks look rough, full, encrusted and singular. This makes the Whites seem porous to the world and the Blacks closed to it, which is largely how they were received. In keeping with his own desire to suppress authorship and to invite indeterminacy, John Cage called the White Paintings ‘airports’ for ambient accidents of light, shadow and dust. ‘If one were sensitive enough that you could read [them],’ Rauschenberg added, ‘you would know how many people were in the room, what time it was, and what the weather was like outside.’ For their part the Black Paintings insist on objecthood in ways that go beyond ravaged surfaces; tacked directly to supports, they were presented without frames, and Rauschenberg often photographed them among everyday things. As the curator Walter Hopps commented, they also underscore ‘the fact of a new urban surface’.

Nevertheless, the two series do share an essential operation in negation. After two White Paintings were exhibited in September 1953, Cage offered this litany: ‘No subject/No image/No taste/No object/No beauty/No message/No talent/No technique (no why)/No idea/No intention/No art/No feeling/No black/No white (no and) …’ Yet the negation of these attributes is an affirmation of many others. As Cage demonstrated in 4’33”, a piece for piano inspired in part by the White Paintings in which nothing is played for that exact duration, there is no silence in music that is not also an opening to sound of other sorts, and so it is with these monochromes: the visual realm is opened up even as it appears to be evacuated. The Black Paintings also point to a space outside painting, which Rauschenberg called the ‘gap between art and life’, and it was capacious enough to contain the Elemental Sculptures as well as the Combines – combinations of painting, collage and sculpture – to come. ‘I don’t want a picture to look like something it isn’t,’ Rauschenberg told the critic Calvin Tomkins. ‘I want it to look like something it is. And I think a picture is more like the real world when it’s made out of the real world.’

Rauschenberg did more than present painting as an object. In colour and texture it was as though the Black Paintings were passed through a giant body, and this scatological association holds, through the psychological link between faeces and money posited by Freud, for the Gold Paintings that Rauschenberg began to produce in late autumn 1953. If the Black and Gold paintings allude to excrement, the Red Paintings, initiated at the same time as the Gold, suggest blood; they include more found material, more ‘real world’, too. Following his own base materialism, Rauschenberg soon moved from the corporeal to the earthly, with works that didn’t merely include dirt (Jean Dubuffet had done as much several years before) but actually consisted of it. In a lost piece titled Growing Painting, Rauschenberg placed earth, seeds and grass in a wooden box, watered it regularly, and displayed it on the wall. For a time this early instance of environmental art had a life of its own.

The Fulton Street studio was close to the fish market, on the top floor of an old sail loft; it had high ceilings but no water or heat (the rent was $10 a month). The world inside was primitive, while the world outside was chaotic, a mix of wood houses, loft buildings and skyscrapers. From the streets Rauschenberg scavenged stuff like old bricks, wood blocks and metal scraps to produce his Elemental Sculptures. Most of these materials, broken and abandoned, suggest a history of hard use, even proletarian labour; they are without the charm of the crafted objects that appealed to the Surrealists, outmoded things marked by personal touch. Rauschenberg treated these discards almost as he found them, arranging them as simply as possible. As Hopps argued, they dramatise ‘basic physical phenomena: gravity, constraint, suspension’, and so invoke both ‘essences of geometry’ and ‘paradigms of natural order’.

By the same token, though, they dramatise basic sculptural conditions and so invoke models of cultural order as well. One work, a corroded iron spike hammered into an old wood block, presents the primordial verticality of sculpture, not only of figurative statues but also of abstract stelae, which modernist predecessors such as Brancusi and Barnett Newman had recalled too. Another piece, a rough chunk of concrete held by a pike and rods above three mortared bricks, declares the fundamental tension in sculpture between weight, support and collapse. Another, an oblong stone loosely roped to a long block with three nails, reduces composition to the most basic of arrangements. In direct ways, then, the Elemental Sculptures juxtapose tokens of nature and culture, the raw and the cooked (Lévi-Strauss puzzled over these oppositions during the same period).

The found objects in the Elemental Sculptures are not charged trouvailles in the manner of the Surrealists, but neither are they cynical readymades in the mode of Duchamp; they thus resist the surrender of postwar sculpture to the logic of either the sexual fetish or the commodity fetish. A committed pragmatist (John Dewey was big at Black Mountain), Rauschenberg favoured material facts, which he stressed in a way that complicates our inclination to reduce meaning to artistic intention or to project human attributes onto things. His many Cagean statements register his aversion to the intentional fallacy, while he once summed up his aversion to the pathetic fallacy as follows: ‘I used to think of that line in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, about “the sad cup of coffee”. I’ve had cold coffee and hot coffee, good coffee and lousy coffee, but I’ve never had a sad cup of coffee.’

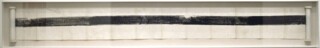

Two actions performed at Fulton Street proved more consequential than either the stark monochromes or the Elemental Sculptures. Automobile Tire Print and Erased de Kooning Drawing, the first a gesture of marking, the second one of unmarking, were executed close in time in autumn 1953, and though they weren’t shown publicly during the 1950s, they were discussed in relation to each other from the beginning. To make Automobile Tire Print, Rauschenberg glued together twenty sheets of drawing paper to produce a strip of 23 feet; then on a quiet Sunday he laid the paper down on Fulton Street and had Cage drive his Model A Ford slowly down its length as he applied black paint to a rear tyre. With its long, literal impression, Automobile Tire Print insists on the horizontal axis of its making, which subverts the conventional verticality of the image. In this way it presaged the reorientation of the picture plane that the critic Leo Steinberg declared, 15 years later, to be ‘expressive of the most radical shift in the subject matter of art, the shift from nature to culture’ – a move towards a postmodernist conception of the image that is credited to Rauschenberg above all.

If Automobile Tire Print launched a thousand actions and happenings, Erased de Kooning Drawing prompted just as many gestures in conceptual art. Sometime in 1953 Rauschenberg convinced the older artist to give him a drawing to erase. De Kooning didn’t make it easy, though, selecting an example that involved pen as well as pencil and crayon. The erasure of this work is often seen as an Oedipal act of iconoclasm, but Rauschenberg admired both the man and the art and downplayed the aggressive aspect of his piece. As the White and the Black Paintings revised the apocalyptic rhetoric of the modernist monochrome of Kazimir Malevich and others, so Erased de Kooning Drawing repositioned the vaunted gesture of Abstract Expressionism, which, like Automobile Tire Print, it redirected to other ends. In fact Erased de Kooning Drawing looks ahead not only to the dematerialisations of conceptual art but also to the framing strategies of institution critique. With its clean mat, gold-leaf frame and hand-printed label, it asks us to reflect on the significance of these overlooked devices.

In summer 1953 Rauschenberg worked as a handyman at Stable Gallery in midtown Manhattan, and used his charm to get its director to offer him a joint exhibition with Cy Twombly in the autumn. The two artists interspersed their art throughout the gallery; while Twombly showed paintings and drawings, some of which were completed at Fulton Street, Rauschenberg exhibited two White Paintings, at least six Black Paintings and most of the Elemental Sculptures. The reception was largely hostile; for the most part Rauschenberg was understood as neo-Dada and neo-Dada as anti-art. (‘What’s the matter with him?’ Newman is said to have said of the White Paintings. ‘Does he think it’s easy?’) To Rauschenberg this was all a misreading; in his Cagean orbit Dada was filtered through Duchamp and didn’t mean anti-art so much as the complication of authorship through strategies of chance and collaboration.

The Stable Gallery show illuminated the Fulton Street studio as a space of artistic exchange. It was here that Rauschenberg not only revised the avant-garde devices of the monochrome and the found object, but also developed his notion of art as a matter of interaction. The interlocutors in this conversation are now well known. First was Cage, who left his mark on far more than Automobile Tire Print. If the White Paintings influenced the composer (‘The white paintings came first,’ Cage acknowledged graciously, ‘my silent piece came later’), the composer affected the Elemental Sculptures in turn. The found scraps of material in these sculptures are not unlike the found bits of sound in his music: both aim less to disrupt the work of art than to render it porous to the world.

A more distant point of reference was the Italian artist Alberto Burri, whom Rauschenberg visited in Rome in March 1953; Burri had a show at Stable Gallery after Rauschenberg and Twombly. Rauschenberg thus saw some of Burri’s Sacchi there, and these abstract works painted on burlap sacks seem to have influenced his Red Paintings in particular. Yet the European and the American had different attitudes to painting. Burri cut his burlap and other fabrics in a way that registered a war-torn world, but he also stitched them up again; like the surgeon he once was, he worked primarily to repair composition and to restore painting. With his monochromes Rauschenberg challenged composition, and his Combines crashed through painting altogether into a literal objecthood that Burri never embraced.

A similar difference separated Rauschenberg from Twombly, who became his close companion after they met at the Arts Students League in New York in winter 1951. Twombly drew on classical subjects and personal impressions alike; if the White Paintings ‘have no history’, as Rauschenberg once insisted, the whitish paintings of Twombly are steeped in it. The sculptures made by the two friends present a similar contrast. In Rome, while Rauschenberg was drawn to vernacular things in the flea markets, Twombly focused on ancient artefacts in the art museums, and at Fulton Street, while Rauschenberg treated his objects as though they were found on construction sites, Twombly made his sculptures as if they had been unearthed in archaeological digs. (This difference is underscored in presentation: Rauschenberg usually put his sculptures on the floor, while Twombly always placed his on bases.)

The relationship with Johns was even more dialogical. The two men met in winter 1954, so their story unfolds primarily after the Fulton Street period, yet two hypotheses can be hazarded. First, with his monochromes Rauschenberg prodded Johns to develop his own painterly literalism, which was concerned less with the facts of the ‘real world’ and the ‘gap between art and life’ than with the failures of meaning and the limits of language. Second, with his Elemental Sculptures Rauschenberg pushed Johns to explore the use of fragmentary extensions and enigmatic analogues of the human body; Johns made these devices his own.

What are the key lessons of Fulton Street? One is that the neo-avant-garde as represented by Rauschenberg and friends is no simple repetition of the models of the historical avant-garde. Then, too, his untimely art looked ahead as well as back, and so anticipated the interests in material process, conceptual gesture and performative action that would dominate the advanced art of the 1960s and beyond. Finally, Fulton Street showed that a studio can be a place not only of practice but also of knowledge (as the etymology of ‘studio’ suggests) and, even more, of creation through collaboration. This is a lesson that Rauschenberg put to excellent use throughout his long career.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.