Born into a progressive family in Königsberg in 1867, Käthe Kollwitz was encouraged by her father, a stonemason and an early member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), to study art – a rare path for a young woman from a working family and a difficult one given that most academies were restricted to men. Kollwitz, no modernist, gravitated to printmaking as the best vehicle for her realist convictions and political commitments, which August Bebel, a founder of the SPD, helped to focus with his treatise Women and Socialism (1879). By 1891 she had settled with her husband, a doctor, in Berlin, where she sketched patients in his waiting room and workers in their Prenzlauer Berg neighbourhood. Destitute women became a primary subject of her art, and she often featured her young sons, Hans and Peter, in her pictures of proletarian families. Searching self-portraits – Kollwitz produced more than a hundred in all media – also punctuate her oeuvre, which is meticulously surveyed in the current retrospective at MoMA (until 20 July).

Largely self-taught as a printmaker, Kollwitz favoured the precision of etching in the first two decades of her work. After 1910, in search of a more gestural approach, she preferred the fluidity of lithography, and in 1920, spurred by the work of the Expressionist Ernst Barlach and a commission to commemorate the murdered Karl Liebknecht, she turned to the dramatic contrasts of woodcuts. Yet the subjectivism of the Expressionist painters remained foreign to Kollwitz, and she was even more remote from the radicality of the Berlin Dadaists, both aesthetically (she never used photography) and politically (she remained loyal to the SPD). Distinctive though her art is, it evokes precedents from Rembrandt through Goya and Daumier to her compatriot Max Klinger: she aimed to bend the bourgeois tradition of printmaking to her proletarian content, not to break with it. ‘Genius can probably run on ahead and seek out new ways,’ Kollwitz once remarked. ‘But the good artists who follow after genius – and I count myself among these – have to restore the lost connection once more.’ Exemplary in this respect is her lithograph from 1903 of a seated nude seen from the back, a traditional motif if ever there was one. Although Impressionists such as Degas had updated it, Kollwitz was opposed to their voyeuristic views: she made her back intimate. This is a body felt phenomenologically, from the inside, almost sculptural across the shoulders where weight is carried, but soft in focus towards the bottom where pressure is eased. Kollwitz scraped her lithographic stone with needles, and here as elsewhere this scoring of the image conveys a marking of the flesh. A history of struggle, social as well as individual, is registered in her bodies.

While her dramatic print series, A Weavers’ Revolt (1893-97) and Peasants’ War (1902-8), brought Kollwitz recognition, individual images such as Woman with Dead Child (1903) and Never Again War! (1924) made her famous. Inspired by a Gerhart Hauptmann play about a failed rebellion in Silesia in 1844, the six etchings of A Weavers’ Revolt are indeed theatrical. In the dismal interior of Need, a mother, head in hands, watches over a starving toddler in bed as the father and a sibling look on helplessly. In Death, a skeletal agent comes for another child, a fate the parents passively accept. The action turns on the third print, Conspiracy, which depicts four men huddled around a pub table. In the fourth, assembled weavers, armed with picks and axes, march towards the city, and in the fifth the men clamour at its gates while the women extract stones from the street. Finally, End shows yet another desolate room where young weavers, killed in battle, are laid out by comrades and mourned by mothers.

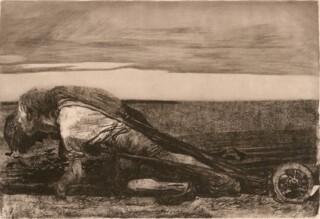

The seven etchings of Peasants’ War reach further back in German history to the agrarian rebellion of 1524-25, which, in the wake of the Reformation, struck at the Church as well as feudal lords. Like A Weavers’ Revolt, Peasants’ War recalls the uprisings of 1848-49 and speaks to proletarian unrest in the present, and it too tells a vivid story. In The Ploughmen, two workers, yoked to each other, appear almost prostrate beneath a lowering sky; they seem to be digging their own graves as much as tilling the barren soil. Meanwhile, the victim in Raped is sprawled on her back, almost formless in the field into which she sinks, literally undone. Here both brute labour and sexual violence are depicted on the horizontal, as the twin triggers of the uprising to come. Once more the hinge of the series is the third etching, Sharpening the Scythe, which Kollwitz struggled over. It shows a peasant woman who, at once enraged and exhausted, rests her head on the blade that she grinds, an allegorical figure of death transformed into an actual avatar of retribution. Its square format underscores the passage from the horizontality of oppression to the verticality of revolt, which arrives in the next etching, Arming in a Vault, where rebel revenants ascend from the dark with scythes carried aloft like swords. In Charge, the peasant woman has become Black Anna, the legendary leader of the rebellion; we see her great body from behind as she rouses a crowd of peasants, brandishing blades, pitchforks and sticks, to storm the town of Heilbronn. The horizontality of the image now conveys the onslaught of the peasants, and the desperate clutch of hands in Sharpening the Scythe is transformed into a dramatic signal to fight. Battlefield depicts the grim aftermath of the uprising: Anna is replaced by a shrouded mother who reaches down to touch her dead son; the only light is a pallid glint on her bony fingers and his cadaverous head. Finally, in The Prisoners, we are returned to the horizontality of oppression: a dense mass of men, bound and bowed, inside a roped pen.

Although she was dismissed by modernists as long on content but short on form, Kollwitz is a very reflexive artist, and one key operation is her persistent shifting between horizontal and vertical figures and formats. Paradoxically, her subjects are never freestanding, as though to underscore, formally, that such autonomy is hardly guaranteed for peasants and proletarians. Except in scenes of protest or revolt, they usually appear bent over, weighed down by the sheer gravity of labour, violence, sorrow, age, mortality. However, even as they cringe before power or poverty, her workers also protest against them; though destitute, they are rarely creaturely, however deformed by suffering or deranged by pain they might be. Also paradoxically, her figurative art features crowds more than individuals, which points to a general problem for art of this period, a problem addressed more effectively in photography and film: how to represent the new reality of the great masses? As telling as her bent figures are her huddled groups, who come together in solidarity as well as in suffering. (‘Huddle’ derives from the low German for ‘conceal’, as the four weavers are concealed in Conspiracy.) Sometimes, too, Kollwitz transforms her huddled groups into vectors of force, as in Charge. Exhaustion favours the horizontal axis as well, but sleep brings no rest for her workers: here, sleep is a state close to death (not to birth, as Brancusi, say, depicts it).

In some images, such as Raped and Battlefield, figures are given over to indistinction, while in others, such as the extraordinary Woman with Dead Child, they are threatened with inanimation. Does the desperate mother pull her inert son up towards life again, or does he pull her down to death? So intense is her embrace that a contemporary critic described her as ‘swallowing back’ her son. Of course, death is the absolute leveller. In Memoriam Karl Liebknecht (1920), based on a drawing made at the morgue, shows the founder of the German Communist Party already turned to wood: as the two ploughmen dig their graves, so Liebknecht merges with his coffin. He becomes an altar for the mourners who hover over him.

Kollwitz modelled this image on the dead Christ, a recurrent theme among old German masters such as Holbein and Dürer, and the allusion to the Lamentation is even more explicit in earlier images such as The Downtrodden (1900). As Renaissance artists turned classical sources towards Christian ends, so Kollwitz repurposes Christian tropes in her socialist representations of peasants and proletarians. Along with the Lamentation, she evokes the Pietà, after which she titled early versions of Woman with Dead Child. Kollwitz modelled for this picture, as did her son, Peter, and this prefigured their own fates: she allowed her underage child to enlist in the First World War, he died in his first week at the front, and she regretted her decision bitterly for the rest of her life. Kollwitz was a socialist Madonna of sorts, then, and sometimes she does evoke the Holy Family in her images of impoverished households. Finally, she plays on yet another Christian subject, the Dance of Death, also a favourite of German masters, who treated it in woodcuts, even as she sharpens the maudlin iconography inherited from academic artists like Arnold Böcklin. All these subjects concern suffering and sorrow, so Kollwitz usually presents them in horizontal formats. However, she shifts to the vertical for her scenes of revolt, where she repurposes predecessors closer in time and more secular in spirit such as Delacroix. His allegorical Marianne at the barricades in Liberty Leading the People (1830) stands behind her Black Anna in Charge as well as her protester in Never Again War!, which Kollwitz produced for the tenth anniversary of the declaration of war on France (it commemorates her son too). Both Black Anna and the protester rise up with extended hands, seizing the moment: Kollwitz turns a bourgeois affirmation of liberty into a peasant summoning others to battle in the first instance and, in the second, a proletarian denouncing a war that killed millions of workers – a war that her SPD, alas, supported. ‘I should hardly mount a barricade,’ Kollwitz once commented, ‘now that I know what they are like in reality.’

These two images are among the most iconic in the show, one of the many merits of which is to demonstrate, through studies and tests, how Kollwitz developed her distinctive gestures and postures – the skeletal fingers, the upraised arms, the bent figures, the huddled groups, and so on. From first sketch to final state we see her strive to get her images just right for printing. Clearly she aimed not only for effectiveness in the present – ‘I want to exercise an influence in my own time’ – but also for resonance into the future. Her expressions are meant to capture social attitudes, along the lines of the ‘gestus’ theorised by Brecht for his plays, as well as mnemonic traits, along the lines of the ‘formulas of passion’ that Aby Warburg detected in post-classical art. And sometimes, as in Woman with Dead Child and Never Again War!, where the historical reference does augment the contemporary impact, she succeeds in both endeavours. In the end Kollwitz might be seen as an artist of ‘obstinacy’ in the sense developed by Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt, that is, the dogged persistence of distinctive attributes of labouring and suffering over generations. Walter Benjamin once remarked that the memory of oppressed ancestors is more catalytic of rebellion than any dream of liberated descendants; Kollwitz seems to agree. However, iconic images aren’t necessarily simplistic ones. Sometimes her signature motifs are multivalent: scythes turn into banners and vice versa; the hand that clutches a dead child becomes a hand that raises a revolt; the embrace of a couple expresses erotic ecstasy here and mortal anguish there.

In the 1920s, as the situation of the German left became more dire, Kollwitz favoured lithographs and woodcuts for their impact and circulation, while in the 1930s, as the Nazis rose to power and her opportunities for exhibition and publication were curtailed, she resorted to sculpture. (The first woman to be appointed as professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1919, she was forced to resign in 1933, a timespan that matches the Weimar Republic exactly.) One understands the political exigencies, but the artistic results are mixed. For the critic Benjamin Buchloh the ‘almost monolithic blackness’ of her woodcuts and sculptures ‘expressively voices the silence of the speechless’. That’s true, but her massed figures in these media sometimes lose definition and strain after effect. This raises the question, then as now, of the extreme pathos of her art. ‘The work of Käthe Kollwitz is the greatest poem of this age in Germany, a poem reflecting the trials and suffering of humble and simple folk,’ Romain Rolland wrote. ‘This woman with her great heart has taken the people into her mothering arms with sombre and tender pity.’ The art historian Wilhelm Worringer took a different view: ‘It is not the misery or the proletariat which she draws, but her feelings for both. This quiet but insistent sentimentalisation might flatter those concerned, but instinctively they will also sense the distance.’ Worringer became tainted by association with the Nazis, but he is not wrong here. Nevertheless, it is this pathos that made Kollwitz so influential, and her impact was international in scope: her work was one model for the socialist realism promulgated in post-revolutionary Russia and China, and it also informed American artists of colour such as Jacob Lawrence, Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett (a genealogy traced in a superb exhibition curated by Buchloh with Michelle Harewood for the Reina Sofía in 2022). At moments one wonders why Kollwitz was embraced so readily: sometimes her workers appear degraded and her crowds look bloodthirsty, as do the revolutionaries that dance around the guillotine in La Carmagnole (1901). So, too, her art makes suffering seem natural, even eternal; there is not a glimmer of utopia on her dark horizons, and if any affect countervails her sentimentality, it is not hope but righteousness. Her self-portraits are also severe, without a trace of humour.

Kollwitz died a week before Hitler killed himself and two weeks before Germany surrendered, and her final images are dominated by dying children and suffering mothers. Nasty though it is to say, this made her the ideal artist to recover after the Second World War. An anti-fascist for both Germanies, she qualified as a non-communist for the West and a non-modernist for the East. This also meant that two subsequent generations of Germans were saturated with her work: she had the dubious honour of becoming a cliché on both sides of the border. However, in the West she was soon shunted to the side by advocates of abstract painting and neo-avant-garde experiment alike (Clement Greenberg, for example, deemed Kollwitz a great personality but a minor artist). Today this is no longer the case: freed from these old biases and prompted by feminist art historians, viewers can come to her work with fresh appreciation.* The show at MoMA is well timed in other ways too. Figuration is everywhere in contemporary art, and many are now committed to the social justice that Kollwitz long championed. Finally, the great manual skill of her art is also seductive (MoMA offers magnifying glasses with which to examine each mark), all the more so at a time in our digital retooling when that tradition of labouring, which, like so many others, Kollwitz sought to carry forward, seems threatened with extinction.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.