Numbers 130 and 131 Fleet Street are today occupied by a branch of the sushi chain Itsu and one of Jeeves (‘London’s Finest Dry Cleaners’), but in 1501 this was Wynkyn de Worde’s home and printing house: he rented a former inn for £3 6s 8d a year from a priory in Buckinghamshire. De Worde would have looked out at the cistern house of the Fleet River; on a weekday morning now, the glass and chrome of Shoe Lane is full of suited twentysomethings. A few minutes’ walk up Fleet Street brings you to Number 188, to the west of St Dunstan’s Church, opposite Ye Olde Cock Tavern, and in an echo of Peter Blayney’s central themes (the business of books, and the Reformation), close to the publishers D.C. Thomson (the Beano, the Dandy, Scotland’s Sunday Post) and the Protestant Truth Society. The printer Richard Pynson worked from here; the black-letter colophon to his A ful deuout and gostely treatyse of the imytacion and folowynge the blessed lyfe of oure moste mercyfull sauyoure cryste (1517) declares: ‘This boke Inprinted at London in Fletestrete at the signe of the George by Richard Pynson Prynter unto the Kynges noble grace,’ so the building was probably hung with the sign of George and the Dragon. As I enter the lobby of the current occupiers, Legalease, the security guard says: ‘You’ve been wandering up and down for about ten minutes. I’ve been watching you.’

In 1501 the Stationers’ Company was a trade organisation without a royal charter, serving some, but not all, of the printers, publishers, distributors and booksellers involved in the London book trade and ‘thoroughly undistinguished’, in Blayney’s words, particularly by comparison with prestigious incorporated companies such as the Mercers, Grocers, Drapers, Fishmongers and Goldsmiths. Many of the most active printers in the early 16th century – including the boom years of the Edwardian Reformation – were not among its members. Thus, as Blayney shows, the Stationers’ involvement with civic ceremony, expressive of a kind of cultural status, was for a long time pretty feeble: in 1509 they were conspicuous for not being among the 48 companies which took part in Henry VII’s funeral procession. By the 1530s, though, things were perking up, at least if we take the seating plan for a lord mayor’s feast as a marker of prominence in the City: four stationers shared a table with a mix of innholders, founders, poulterers, scriveners, broderers and upholders – and we can imagine them holding their conversational own, over the capons and teal.

What changed on 4 May 1557 was incorporation: a charter endorsed by Philip and Mary granted the Stationers a nationwide monopoly on printing, and the right to seize, burn or amend illegal books; to buy and sell property; to bring lawsuits in court; to gather whenever they wished; and to elect a master and two wardens every year. For the Stationers, Blayney writes, the charter was a means ‘to enforce their new commercial monopoly’. For the Crown, it was part of a broader attempt to regulate the printing industry, and accompanied a Marian purge of a book trade previously dominated by printers ‘who owed their commercial success to the Edwardian Reformation’. Less than three weeks after Mary arrived in London, she issued a proclamation condemning the ‘pryntynge of false fonde books, ballettes, rymes, and other lewde treatises in the englyshe tonge … touchynge the hyghe poyntes and misteries of christen religion … for lucre and couetous of vyle gayne’.

Throughout these two monumental and field-defining volumes, Blayney’s tone in discussing recent work in book history brings to mind the facial expression of someone who has just sucked a lemon. Bibliography ‘has been stretched so far beyond all useful limits, and has been said to include such a confusing variety of barely related meanings’; ‘the only sentence in this book in which the words print and culture both appear is this one.’ His work may be of interest, he concedes, to textual and literary scholars – ‘where both inventors and consumers of book-trade fallacies have flourished’ – but such interpretative pay-off is ‘merely a by-product’. Blayney’s subject is printed books and ‘the people who manufactured, distributed, and retailed them in London’, between 1501 and 1557. His focus is the capital, but he also richly details provincial presses in York, Oxford, St Albans, Cambridge, Tavistock and Abingdon, as well as imports from abroad. Often these busy printing houses are hanging by a single, slender thread: the only known remnants of the noisy bustle of printing in 16th-century York after 1519 are three sheets from a single copy of Stanbridge’s Accidentia (1532), printed ‘in yorke at the sygne of the Cardynalles hat by Iohan warwyke’.

Since the usual biographical sources for the book trade are what he calls ‘hopelessly obsolete’, Blayney inches through wills, court records, parish registers, orphanage recognisances, royal accounts, churchwardens’ accounts and tax assessments. None of these sources, of course, were composed with future historians of the book trade in mind, but sometimes their swooping searchlights illuminate the figure we’re after for just long enough. You have probably never heard of Anthony Scoloker, or Ursyn Mylner, or John Gybkin or Lodowick Harbard, but Blayney reveals probably as much as it is humanly possible to know of their teeming world. When John Warwick died in York in 1542, his inventory listed not only one cow and six silver spoons, but also the contents of his ‘pryntynge chambre’, including ‘the prysse with iij maner of letters [three fonts of type] with brasse letters [ornamental initials]’, along with materials for binding: ‘v dossen barkyde skynnys [tanned skins]’ and ‘x hundreth bordes for bookes grett & smalle’. Court records offer vivid portraits, although (as Blayney is careful to note) they create a transgression-heavy sense of the book trade: a life of quiet, steady work leaves little trace. More visible are the pewterer and shoemaker who were whipped ‘arse naked’ while tied to a cart being drawn through the City’s marketplaces in April 1545. Papers pinned to the cart declared their offence in ‘castynge abrode … certeyn sedicious bylles directly ageynst goddes lawes & the kynges’.

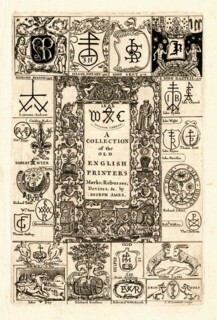

Printed books themselves become, in Blayney’s hands, documents of their own production. We naturally focus on a book’s literary narrative, but there is a material narrative there too – a story of the making of the book – if we learn how to read the signs. Sometimes lost books can be brought back to life. A book of prayers and a primer, printed by John Wyer, are known now only because one of each was torn up and used to make endpapers in a copy of A boke made by Iohn Fryth prysoner in the Tower of London answerynge vnto. M. Mores letter (1548). Sometimes errors in printing provide a glimpse inside the printing house. By looking very closely at the appearance and reappearance of irregular pieces of type – a cracked ligature here, a missing dot on an ‘i’ there – Blayney is able to trace bonds of professional exchange, kinship and allegiance. When Reyner Wolfe printed Robert Recorde’s The Ground of Arts – a bestseller, ‘teachyng the worke and practise of arithmetike, moch necessary for all states of men’ – Wolfe borrowed eight initials, two ornaments and some textura fonts from John Herford. And a small number of sheets printed by Thomas Berthelet and Thomas Godfray around 1536 feature what Blayney calls ‘disoriented 4s’ – ‘whoever struck the matrix from which the 4 was cast did so with the punch rotated ninety degrees anticlockwise from its correct orientation’ – which suggests both printers were using type from a single foundry. As a result of tracking hardware in this way, Blayney shows how the book trade was genealogical in structure: widows inherited their husband’s stock; sons followed fathers, and apprentices their masters.

The material instantiations of the nation’s lurching Reformation history can be seen in extant physical books today. Edward VI’s 1549 Act of Uniformity required every parish to obtain a copy of the Book of Common Prayer: a boon for printers, but an expensive demand on parishes, which raised money by selling off old Latin liturgical books, usually as scrap parchment – the bindings stripped and sold separately – or occasionally for what Blayney calls ‘illicit devotional use’. When John Knox attacked (with characteristic thunder) what he saw as lingering Popish elements in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer, the ‘Order for the Administration of the Lord’s Supper’ was duly revised with a Protestant gloss on kneeling as gratitude, not adoration: the printers Grafton and Whitchurch scrambled to print correction slips to be added to as many unsold copies as possible, and also distributed them to those who had already bought the book. Extant copies of the Book of Common Prayer reflect this shifting theological terrain: earlier copies often omit the revision; some carry the text on a separate page (‘it is not ment thereby, that anye adoracion is … for that were idolatry’); and later copies – like the Bodleian Library example I’m looking at as I write, owned by the 17th-century bishop of Lincoln, Thomas Barlow, and decorated with handwritten pointing fingers lurking in the margins – incorporate the revision among the Communion instructions.

Blayney shows, too, how technically difficult printing forced printer-publishers to look overseas. The French were better at printing in red and black, and so two-colour liturgical books were often imported from abroad. The greatness of the Great Bible (1538) was in part a product of its physical heft: printed on large demy paper, an unbound copy was ‘more than a quarter of a cubic foot of paper’, Blayney notes, ‘and weighed 11 pounds 6 ounces’. No English printer had a press large enough to cope, and Blayney takes us through a complicated story of Anglo-French collaboration between Richard Grafton, Edward Whitchurch and François Regnault which (Blayney demonstrates) doesn’t fit neatly into a history of the book that, in other hands, has often been organised around nation states.

If you want to know about the contents of the books whose physical form Blayney so brilliantly anatomises, these probably aren’t the volumes for you. Indeed, if you simply want to know the titles, Blayney’s text is often unyielding. This is a principled position, since Blayney laments that ‘the study of books without regard to their contents no longer has a name of its own.’ But you may, for instance, be intrigued to read about the first four books printed by John Rastell, the earliest native-born printer in England. Blayney notes in parentheses that the third of the books is Thomas More’s translation of the life of Pico della Mirandola, but for anything more you’ll need to chase an endnote which takes you to the unlovely sentence ‘STC 9895, 23153.8; 19897.7; 15635.’ From here, you’ll need to consult the Short Title Catalogue (if you’re fortunate enough to have access to it) before these numbers can blossom into the titles they really are. You might then be struck by the fact that the English-born Rastell printed a book for schools about Latin grammar, written in English: Thomas Linacre’s Linacri progymnasmata grammatices vulgaria, in 1512. The effect of Blayney’s lack of interest in this sort of thing is that it descends down to printers and publishers: it is self-fulfilling. But did Rastell’s biography and subject matter entangle with a sense of an emerging vernacular vitality?

The Stationers’ Company is an expression of a quantity of archival labour and expertise that may never be surpassed: it is a great piling up of new, neglected or (Blayney’s favourite category) disastrously misunderstood pieces of archival evidence. ‘My motive,’ Blayney claims, ‘is not to cram in every trivial scrap just to prove that I have done the research,’ but he certainly appears keen for us to feel the weight of his work (‘I record virtually every mention of any printer, Stationer, or other person active in the book trade that I have found’). This commitment to exhaustiveness creates a kind of laudable blizzard. A 1511 deposition’s description of printer Richard Faques’s facial ‘blemysshe’ indicates not a scar, but a birthmark; Wynkyn de Worde’s shop frontage ‘was a respectable 31 feet 3 inches’; on 21 December 1519, the printer Henry Pepwell paid 3s duty on one ‘lyones’, probably imported for ‘a travelling showman’ or a patron like the Earl of Kent. A vignette – and possibly a historical novel – flickers for a second; but then the book presses on, to the next fact, presented like a gem on a cushion. It is difficult to know how to respond. The Stationers’ Company is aggressively chronological: it inches through the 16th century, year by year (‘the next printer to set up shop in London was John Wayland’), rejecting thematic organisation because ‘Stationers, printers, binders and others lived their lives from year to year rather than topic by topic.’ But this commitment to a chronicle model collides with the book’s organisation into slices of times (1510-20; 1521-28; 1529-34 etc), meaning that figures with long lives crop up, then fall away for a hundred pages, then appear again. The effect is of resuming a cocktail party conversation mid-sentence, thirty years later. In some ways, then, this is not quite a book at all: it’s an archive, a huge trunk of very exact things assembled by one man over thirty years, and what book historians do with it all will unfold over the next couple of decades.

In this sense The Stationers’ Company is a generous book, but if you’re cited in the text it is probably best to take a large measure of whisky before proceeding: the ‘familiar edifice’ of book history, Blayney writes in a sentence that combines the registers of Jeremiah and the construction industry, ‘is so riddled with misunderstandings, oversights, errors and fictions of various kinds that mere repair is no longer enough. What is needed is demolition and replacement.’ Blayney’s wrecking ball reveals how errors have been ‘germinated’ and repeated with sufficient frequency to acquire the appearance of truth (like W.W. Greg’s description of the 1557 Charter, signed under Mary I, as ‘a masterstroke of Elizabethan politics’). What Blayney calls ‘the road to error’ is littered with illustrious names. Cyprian Blagden’s history of the Stationers’ Company has ‘scarcely a paragraph free of factual errors, unfounded assumptions, or both’. David Daniell’s statistics on Bible printing ‘are both misleading and inaccurate’. A.W. Pollard ‘misunderstood the paragraph almost completely’. Of Lotte Hellinga’s analysis of Robert Redman’s piratical printing practices: ‘Not a word of that is true.’ William Herbert ‘entangled himself in a completely inconsistent line of reasoning, and left the matter far worse than he found it’. This focus on scholarly mistakes leads at times to a weird warping of priorities: an absorbing account of Bible printing lurches off into a very local dispute with a previous scholar about what we mean when we call something ‘conspicuously rare’. Even Blayney’s younger self gets it in the neck: ‘I am unable to explain how I managed to give the wrong date (28 April) twice.’

Blayney promises a sequel that will run to 1616, ‘with the death of the last surviving Stationer who had been freed before the charter’. If the follow-up resembles its forerunner, the history of the book trade will be profoundly enriched for a second time, and a generation of scholars will once more retreat to their rooms, shut their doors, and slowly turn the pages to see where, and with what deadly precision, they have been skewered.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.