I too was ‘a single man’ in the fall of 1999. And like the doomed protagonist, George, in the novel A Single Man by Christopher Isherwood, I too was gay; I too was an English professor (on a one-term sabbatical back then); I too was middle-aged (at 39 years old then, whereas George is 58); I too was living in Los Angeles (although my teaching position is in Iowa City); I too was heartbroken (whereas George has just lost a long-term but considerably younger lover in a car accident, I’d lost my only somewhat younger lover in a break-up). I was writing a book – never to be published – on Proust, or rather on the act of writing such a book. I was reading – and then reviewing for this very publication – a biography of Franz Liszt by Alan Walker.* I was also reading – for amusement – the biography of Lytton Strachey by Michael Holroyd and one of Dorothy Parker by Marion Meade.

In Holroyd’s book, I was most struck by some portraits – reproduced in full colour – that had been done of Strachey; there’s one by Simon Bussy, drawn in 1904 (the year of Isherwood’s birth); there’s one by Henry Lamb, painted in 1914; there’s one by Dora Carrington from 1916. In Meade’s book, I was most struck by the following passage about a party in Los Angeles. (Parker, in addition to writing both poetry and fiction, not to mention reviews for the New Yorker, did a fair amount of screenwriting, and this party must have taken place at about the same time, in the early 1960s, that Isherwood – in addition to his own screenwriting – was at work on A Single Man.)

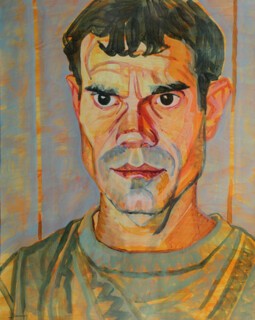

At a cocktail party given by Dana Woodbury, [Parker] entered the living room to be confronted by a life-sized nude portrait of her host, which had been painted by Christopher Isherwood’s talented protégé, Don Bachardy. Woodbury handed her a cocktail, then asked what she thought of the painting. She gazed at it thoughtfully. She didn’t wish to offend Dana, who had once been a Buddhist monk. In the painting he was seated, facing front, and his genitals had been executed with remarkable attention to detail.

I had long known a fair amount about Isherwood; in graduate school I’d read almost all of his fiction, which of course is rather autobiographical (Goodbye to Berlin, Mr Norris Changes Trains), along with a biography of him by Jonathan Fryer. And so I had also long known – a bit – about Bachardy. I knew back then, for instance, that he was considerably more to Isherwood than just a protégé. They had been lovers since 1953, when the writer was 48 and the artist-to-be only 18. They would remain together, I knew, until the death of Isherwood – from prostate cancer – in 1986. I did not know – and nor am I now able to discover – who ‘Dana Woodbury’ was.

Late that fall, I just happened to meet someone – yet another English professor – who just happened to know Bachardy. Would I, he asked, like to meet Bachardy? He still lived, apparently, in the house in nearby Santa Monica that he had long shared with Isherwood. Would I, moreover, like Bachardy to do my portrait? Yes, I would, I said – although not because I knew what Bachardy’s work looked like, or rather how incredibly good it all is. (I did not know this, in fact. Meade does not describe the portrait of Woodbury; nor had I yet seen other portraits by Bachardy.) And also not because I liked the idea of my own genitals being executed, by any artist, with any attention – remarkable or otherwise – to detail. (I did not, in fact, like it.) I said yes because I wanted to see that house. I had – and still have – a thing for almost any writer’s workspace; I’d soon write and then have published an incredibly good and only somewhat autobiographical book on this, Neatness Counts: Essays on the Writer’s Desk. (In it, there’s a chapter on Proust.) I also had, as you may have inferred, a thing for Isherwood – as a writer – in particular. (‘I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking,’ Goodbye to Berlin begins. ‘Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.’)

I got together with Bachardy and the other professor for cocktails, at some quaint little restaurant near the house. Bachardy had walked – or perhaps sprinted – down there from home. He was wearing what I assumed were gym clothes. He had a full head of long, smooth and very silvery hair. He had long, thick and somewhat less silvery eyebrows. He had long, thick and even paintbrush-thick eyelashes. These, though, were a very dark brown. (‘They’re like those of Elizabeth Taylor,’ I thought. ‘Or maybe Montgomery Clift.’) His eyes, too, were very dark – but a very dark green.

He was, moreover, articulate – speaking in full, proper sentences and using no, like, you know, ‘discourse markers’. Although born and raised in Los Angeles, he had the same proper accent – English, Received Pronunciation – that I imagined Isherwood must have had. (I was right about this – as you can hear in the recent documentary Chris and Don: A Love Story. But this was no mere affectation on Bachardy’s part. ‘I can’t help it,’ he says in the film. ‘I’m an unconscious impersonator.’)

He now asked if I would like to ‘sit’ – not ‘pose’, I noticed – for him. He explained that he only ever did life drawing. Bachardy, that is, has never worked – in portraiture – from photographs, nor has he ever reworked a portrait. Every portrait is finished, over and done with, and also signed and dated by both artist and sitter, when a sitting is finished. ‘It’s only ever about process, for me,’ he said, ‘and never about product.’ He explained, too, that he did such work – in a studio just next to the house – almost every day of his life. He did not explain, nor did I ask him to explain, just why he would like to do my portrait – or even that of any such non-celebrity (including, perhaps, Woodbury). Having watched Chris and Don a couple of times, I now know why he wanted to – or even perhaps needed to – do this. It’s only ever about the human face for him, and never about – at least not since an admittedly ‘star-struck’ childhood and adolescence – celebrity. ‘Every face has to be important,’ he says somewhat inarticulately because rather passionately at the end of the documentary. ‘Every face. And when you think each individual is showing me a face that he is living his entire life with – and so it has to be of immense importance.’

I, alone, soon sat for Bachardy – after seeing the house. (I’d suggested if not demanded a tour of it. I’d considered stealing an ashtray at one point. But I then thought, somewhat ashamedly, about how I myself would feel should anyone do such a thing to me.) The studio – bright white – had a great view of the Pacific Ocean. It had, as well, displayed on the walls, any number of portraits done – in colour – by Bachardy. Some of these, I noticed as I entered, were of Isherwood. (In Chris and Don, you get a good look at this studio. You can see the house in it as well. You can see the restaurant where we met in the recent film version of A Single Man, directed by Tom Ford and starring Colin Firth as George.) But since I now removed my glasses – let’s just say that this was at Bachardy’s suggestion – I neither got to enjoy the ocean view, while sitting, nor saw those portraits at all well. The sitting itself – which at times meant reclining – was very painful. I had to hold some awkward position, never moving a muscle, for up to two hours at a stretch. And there were about six such stretches. Clothes were removed – my clothes, that is – after stretch number three. Bachardy himself was seated – on a stool – just a few feet in front of me. He was now wearing jeans and the kind of tight, sleeveless T-shirt that in the United States we call a ‘wife-beater’. He was now staring at me, or rather at various points all over me (including genitals), with remarkable intensity and for seemingly endless minutes at a time. (This, given such close proximity, I could see very well.) He did not speak to me while working. (He did, though, from time to time, mutter to or even scold himself.) And so neither did I speak. All there was to be heard was the sound of brushstrokes (plus muttering or scolding). No music, indoors. Outdoors, no birdsong or traffic noise. He was clearly working very hard, very painfully, perhaps, and with only just a few offbeat colours of acrylic paint, to capture my likeness. (I could see blue paint, for instance, and yet my eyes are dark brown. I could see yellow as well. And was that orange just then?) There had been no preliminary drawing done – in black – on those large sheets of white paper, no sketching. All this work, this whole process, I felt, was almost as much of a confrontation between the two of us as it was a collaboration. And so what, I wondered, must it feel like to be him doing this? (‘What I’m really doing,’ Bachardy says in Chris and Don, ‘is impersonating my sitter when I’m painting.’)

We finished; we signed and dated all the paintings; I alone gazed at them thoughtfully. He had captured my likeness, despite those offbeat colours and what seemed to me even then to be a kind of abstraction at play. He’d captured my essence, rather. I looked, I thought, quite alive in them – if also a bit death-driven. I must look sadder, I thought as well, than I thought I looked. And, better yet, in one nude – not quite life-sized – I looked thinner than I thought. This I now bought from Bachardy – and would later have framed. (I bought the very saddest of the lot, too.) But, unlike Woodbury, I have never been able to hang the nude in my own or rather in our own living room. It’s now in the laundry room of the house that I’ve long shared with my husband, David Coster. (He’s a farm boy turned general surgeon – very handsome, with blond hair and blue eyes – whom I met just a few months after that sabbatical, and he’s also only a few months younger than I am.) And I may well – as either a joke or an only somewhat warranted act of revenge – bequeath it to my English Department.

Bachardy’s recent book, Hollywood, has confirmed for me much of the sense of his art that I now had. It confirms as well a far more general sense – among art critics – that Bachardy, like his friend David Hockney (who drew and painted Bachardy and Isherwood, sitting side by side together in that house), is a major contemporary artist. It is a retrospective of his early drawings (in black and white) and later paintings (in colour) of various movie stars, film directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, costumiers, choreographers, composers, columnists, producers and even agents. (Early on, of course, Bachardy met most of these people – all workers in what Adorno famously and rather snobbily called the ‘culture industry’ – through Isherwood.) Those stars include Fred Astaire, Katharine Hepburn, Angela Lansbury, the much too pretty Teri Garr, the much too beautiful Warren Beatty, Julianne Moore (who also stars in the film A Single Man), Montgomery Clift (with rather more eyebrow than eyelashes), the late, great Joan Rivers (drawn in ink while talking to the gay writer Armistead Maupin, and therefore not self-consciously posing), Rita Hayworth, Natalie Wood, Marlene Dietrich (drawn while posing, clearly), Simon Callow, John Gielgud and Ian McKellen. (My husband, David, incidentally, is related to Dietrich – on his mother’s side.) The screenwriters don’t include Dorothy Parker, although I’m fairly certain that Bachardy once did her portrait in black and white. Bachardy, it seems, did not allow himself to use colour until after he had perfected black and white drawing. Most interestingly, the book juxtaposes early drawings with later paintings of many of these people: first they’re young, and then suddenly they’re older.

What is also interesting is that the book includes as well various very beautiful abstract or, rather, non-representational paintings done – in colour – by Bachardy. (These are, in fact, called ‘Abstracts’.) None of the brief prefatory material – by Tom Ford, who by the way is gay, by Maupin, and by Bachardy himself – mentions, let alone tries to explain, this inclusion. (‘My sitter’s pain is physical and static,’ Bachardy writes, ‘mine mental and frenzied as I hurry to end my obsessing, ravishing torment.’) But it does underscore the increasingly if not quite deliberately abstract quality of the later work, which later work itself underscores the relative realism of the early work. (If his later work seems abstract, Bachardy once said, that’s only because such abstraction is ‘in the air’.) Elsewhere, though, in an essay collection called The Isherwood Century, the gay writer Edmund White finds – and with reason, I think – not so much abstraction in the later portraiture by Bachardy as a kind of landscape painting. ‘Bachardy’s portraits penetrate a face known to a wide audience – through book-jacket photos, postcards of authors, David Hockney’s paintings – and dissolve its exacerbated individuality into a kind of landscape,’ White writes. ‘This cosmic view of the self recalls the art that Bachardy’s drawings do in fact remind me of the most – the paintings of the Chinese artists, especially the Buddhists who broke down the distinction between animate and inanimate and erased the differences among animal, vegetable and mineral.’

Can – and this is as much an English-professor type question as it is an art-critic one – Bachardy be said to have what Adorno, who by the way was not gay, would have considered to be a ‘late style’? Probably not, because what Adorno took as a touchstone was the late style of Beethoven. (‘The maturity of the late works of important artists is not like the ripeness of fruit,’ Adorno once wrote. ‘As a rule, these works are not well rounded, but wrinkled, even fissured. They are apt to lack sweetness, fending off with prickly tartness those interested merely in sampling them. They lack all that harmony which the classicist aesthetic is accustomed to demand from works of art, showing more traces of history than of growth.’ Like, you know, whatever.) Or can Bachardy be said to have what the non-gay writer J.M. Coetzee considered a late style? (‘Late style, to me,’ Coetzee once wrote, ‘starts with an ideal of a simple, subdued, unornamented language and a concentration on questions of real import, even questions of life and death.’) Possibly, because a lot of the later work seems rather death-focused – or at least concerned with what Wordsworth (in an early work) did not quite call ‘intimations of mortality’. (Teri Garr, for instance, in an acrylic painting, looks both very pretty and spiritually pained: her long dark eyelashes now rather smudged; her long blonde hair, done in brushstrokes that are almost much too dry and much too wide, now rather brown.) But then, a lot of the early work seems similarly preoccupied. (Warren Beatty, for instance, in an ink and pencil drawing, looks both very beautiful and positively or, rather, negatively pensive.) Bachardy’s own, private encounter with the long-drawn-out and very painful dying of Isherwood (which took place over several months and which he, Bachardy, as a committed artist and also as a devoted son of sorts to Isherwood, forced himself to document, day after day after day, by doing black and white drawings of the old man, and then even of the corpse: ‘both merciless and loving’ work, according to the allegedly non-gay writer Stephen Spender in the not so recent book Christopher Isherwood: Last Drawings; both ‘ruthless’ and ‘ghoulish’, according to Bachardy himself in his diary), plus, later on, Bachardy’s own inevitable move into old age must merely have intensified a nearly lifelong focus that he himself has had on death – or on the rather sad because also rather beautiful sense that life, every life, is over and done with too quickly.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.